Experimental Archaeology

Experimental Archaeology is an approach for filling gaps in our knowledge about the past, which cannot be filled through other archaeological research methods. An archaeological experiment must always answer a specific research question through practically testing production, use and/or formation of material culture and/or archaeological features. In Experimental Archaeology, testing a hypothesis in direct reference to the archaeological record is the core activity. The information gained should be impossible to obtain from solely examining original artefacts. The practice of experimental archaeology is strongly connected to the other four legs of EXARC as growing craft experience as well as interpretation can also lead to research questions and experimental projects.

Featured Experimental Archaeology Events

There are no results we can show you which match your search query. Please modify your search.

Featured in the EXARC Journal

An experimental investigation of alternative neolithic harvesting tools.

- Read more about An Experimental Investigation of Alternative Neolithic Harvesting Tools

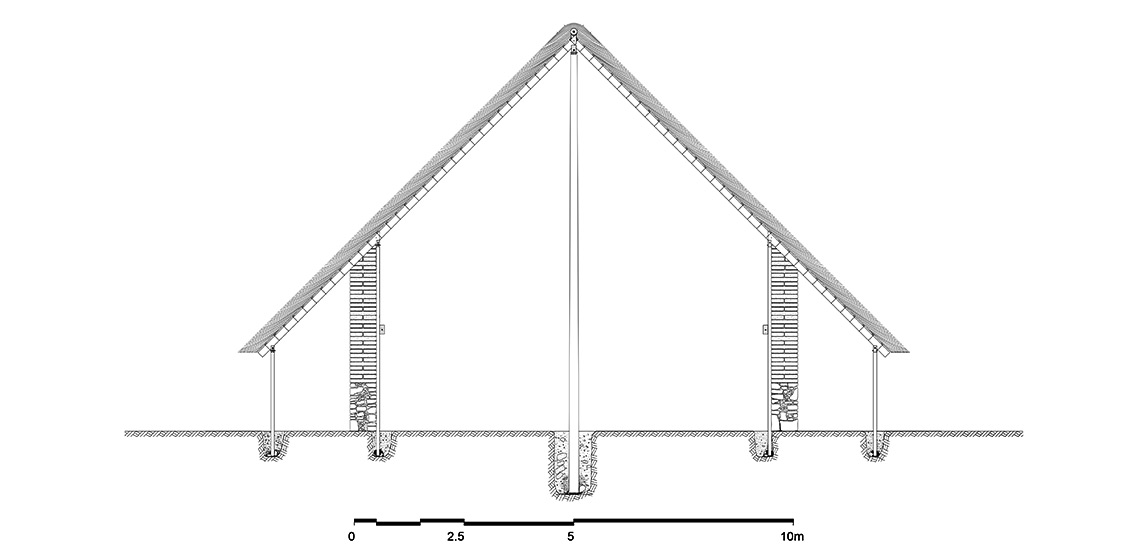

The Lefkandi-Toumba Building as a Timber-Framed Structure

- Read more about The Lefkandi-Toumba Building as a Timber-Framed Structure

Does the Addition of Manganese Dioxide Aid in The Production of An Ember when Using Strike-A-Light Technology With Horse Hoof Fungus? A Potential Neanderthal Technology

- Read more about Does the Addition of Manganese Dioxide Aid in The Production of An Ember when Using Strike-A-Light Technology With Horse Hoof Fungus? A Potential Neanderthal Technology

Higher Education Centres and Groups working with Experimental Archaeology

EXARC includes several higher education centres in its membership. These universities and other adult education facilities offer a wide diversity of courses on material culture, ancient technology and experimental archaeology. We are working on a full list of the universities across the world and wish to list them as well. The groups, associations and foundations who are EXARC member and work with experimental archaeology are also listed on this map. Each is represented with a short story, an exact address and their official website for up to date information. Note: EXARC Members are marked with a red balloon.

Stichting Erfgoedpark Batavialand att. EXARC Postbus 119 8200 AC Lelystad the Netherlands Website: EXARC.net Email: [email protected]

Social Media

Discord Server

EXARC Facebook Page Facebook Group: EA Facebook Group: AOAM

Instagram | Twitter | YouTube Slideshare | Vimeo

EXARC LinkedIn Page LinkedIn Group: EA LinkedIn Group: AOAM

Creative Commons Licence

The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License . If you have any queries about republishing please contact us . Please check individual images for licensing details.

- Reset your password

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Applied Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Biological Anthropology

- Histories of Anthropology

- International and Indigenous Anthropology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Sociocultural Anthropology

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Experimental archaeology.

- Silje Evjenth Bentsen Silje Evjenth Bentsen Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour (SapienCE), University of Bergen

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.325

- Published online: 17 April 2024

Scientific definitions of “experimental archaeology” emphasize key words such as exploring, testing, and imitation. Archaeological data and observations are key elements in experiments, whether the researcher is testing hypotheses derived from archaeological deposits or objects, innovative approaches to documentation and excavation, or the formation of and post-depositional processess affecting the archaeological record. Experiments can be conducted in sterile laboratory settings, with strict control of variables and materials, or in actualistic settings replicating the conditions of the prehistoric settings. Laboratory and actualistic experiments are complementary, allowing testing of different aspects of hypotheses and materials, and it is often essential to explore an archaeological phenomenon through experiments in both settings. Studying fire-cracked rocks and heating of different rock types, for example, can benefit from both heating experiments in a laboratory furnace, allowing observations of temperature thresholds for thermal alterations, and an open-air fire, allowing recording of how a live fire with temperature changes and smoke affects rocks. A third type of experiment is digital, made possible through virtual models and allowing one to replicate and test multiple variables within a controlled setting.

Experimental archaeology also includes non-academic approaches to exploring the past. It contains elements educational both for the person(s) conducting the experiments and for people watching, reading, or in other ways learning about the experiment and its results. Some experiments are experiential—that is, re-enactments or performances. These re-enactments can be part of an educational program, such as demonstrating prehistoric living conditions at an open-air museum, or they may be initiated by, and important to, the experience of the re-enactors. Experiential archaeology has elements of perceived time travel and can be a recreational activity.

- replication

- hypothesis testing

- actualistic

- reconstruction

- innovative use of technology

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Anthropology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 December 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

Character limit 500 /500

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Experimental Archaeology

Introduction, general overviews.

- Useful Journals

- Exploitation of Resources

- Processing, Technologies, and Craft Skills

- Performance and Function

- Site Formation Processes

- Taphonomy and Preservation

- Techniques of Recovery, Survey, Analysis, and Interpretation

- Public Presentation and Engagement

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Archaeological Education

- Archaeology and Museums

- Public Archaeology

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Race and Health

- Anthropology of Corruption

- Digital Nomads

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Experimental Archaeology by Alan Outram , Linda Hurcombe LAST REVIEWED: 28 July 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 28 July 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199766567-0271

Experimental archaeology is a multifaceted approach employed by a wide and rapidly expanding range of exponents including everybody from lab-based archaeological research scientists through to museum professionals and re-enactment groups. Scientific experiments are trials designed to test a hypothesis which will either be rejected (falsified) or validated. Validation does not imply truth, but demonstrates that the hypothesis is viable, though there may be equally viable alternatives. Experiments are the mainstay of almost all hypothetico-deductive science. Hence, one could define most archaeological science as being a form of experimental archaeology. However, most practitioners of experimental archaeology would view an attempt to replicate past activities and processes using authentic materials as an essential, defining aspect of the field. A laboratory scientist’s approach to experimentation is likely to minimize the variables being investigated at any one time while maximising control over conditions. Other experimental approaches, however, aim to see how processes work within life-like scenarios that involve authentic materials and variables. The term “actualistic” is often applied to such a mode of experimentation, alongside “reconstruction” and “replicative.” The best research often involves both controlled and actualistic experimentation to provide a sound understanding of individual variables and the interaction of many variables within realistic scenarios. These approaches are complementary and on a continuum. While some experimental archaeologists view their approach as an actualistic branch of hypothesis-based archaeological science, where the strict definitions of an experiment apply, others view the field as somewhat broader. Such practitioners value what can be learned from attempting to carry out activities, or even live, in conditions and with the materials that would be available in a particular time or place. This type of activity is often not based upon the testing of particular hypotheses but on experiential learning. Exponents of this approach will gain insights into the potential challenges faced by past peoples that might not otherwise occur to us or be reflected in the ethnographic record. Groups of practitioners that fall into this category might variously identify as being “re-enactors,” exponents of “living history,” “primitive technologists” or even “survivalists.” Thus, experimental archaeology can range from strictly scientific and objective methods to more subjective, experiential approaches, while retaining the essential aim of undertaking experiments which usually include actualistic activities using authentic materials. An additional noteworthy attribute of experimental archaeology is that re-enactment and reconstruction activities lend themselves particularly well to engaging forms of public presentation and education. As such, open-air experimental archaeology museums are currently expanding in number and visitorship. This field is expanding exponentially in almost every branch of archaeology making an individual section on every possible topic impossible, thus our approach is indicative and organized by broad themes of inquiry.

Experiments have been used in archaeology as far back as the 1890s, but “experimental archaeology” was not really defined as a specific subfield until Ascher 1961 summarized such activity under that heading. The approach was more fully described and advocated by John Coles in the 1970s in a number of works, the most comprehensive of which is Coles 1979 . The 1960s saw the establishment by Hans-Ole Hansen of the Lejre research and experiment center in Denmark and in the 1970s the establishment of Butser Ancient Farm, a famous site for the experimental investigation of Iron Age structures and farming practices. Its founder and chief scientist was Peter Reynolds who published an overview of his perceptions of experimental archaeology in Reynolds 1999 . More recently, a number of works have provided general introductions to the subject including Hurcombe 2004 , Mathieu 2002 , Millson 2010 , and Outram 2008 . Many of these articles are introductions to edited volumes that are dedicated to experimental archaeology, some of which relate to schools of thought developed in particular geographical regions. For instance, Ferguson 2010 presents largely American and scientific perspectives, while Petersson 2011 presents a less strictly positivist view from Scandinavia, and Reeves Flores and Paardekooper 2014 gives broad overviews of European developments. All these works address varying definitions of experimental archaeology, discuss different types of experiment, and introduce examples. Kelterborn 2005 provides such an overview in the form of a very concise set of principles to guide successful applications of experimental research.

Ascher, Robert. 1961. Experimental archaeology. American Anthropologist 63.4: 793–816.

DOI: 10.1525/aa.1961.63.4.02a00070

An early paper considering the concept of experimental archaeology that provides a set of examples of formative work from the 1890s to 1950s.

Coles, John. 1979. Experimental archaeology . London: Academic Press.

This influential volume was significant in advocating the use of experimental archaeology and takes a thematic approach to discussing the use of experiments within archaeological research.

Ferguson, Jeffery R., ed. 2010. In Designing experimental research in archaeology: Examining technology through production and use . Boulder: Univ. Press of Colorado.

Edited volume with good introductory overview and an American flavor. It particularly focuses on different approaches to experimental design covering a range of artifact technologies and performance issues.

Hurcombe, Linda. 2004. Experimental archaeology. In Archaeology: The key concepts . Edited by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn, 110–115. London: Routledge.

Brief overview of the meaning of experimental archaeology for academic research versus a broader common perception of the term.

Kelterborn, Peter. 2005. Principles of experimental research in archaeology. euroREA 2:119–120.

By summarizing principles he developed in three earlier works, this very short article concisely outlines some guiding principles to the good conduct of experimental archaeology research.

Mathieu, James R. 2002. Introduction. In Experimental archaeology: Replicating past objects, behaviours and processes . Edited by James R. Mathieu, 1–4. Oxford: BAR Archaeopress.

Valuable general summary of the field that discusses the essential components of an experimental approach at the start of an edited volume dedicated to the subject.

Millson, Dana C. E. 2010. Introduction. In Experimentation and interpretation: The use of experimental archaeology in the study of the past . Edited by Dana C. E. Millson, 1–6. Oxford: Oxbow.

A short, balanced introduction to the subject that puts the field within its theoretical context. The rest of this edited volume is devoted to theoretical perspectives in experimental archaeology.

Outram, Alan K. 2008. Introduction to experimental archaeology. World Archaeology 40.1: 1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/00438240801889456

Introduction to a themed journal issue devoted to experimental archaeology which defines experimental archaeology primarily as sitting within positivist science, without denying benefits of other approaches the field.

Petersson, Bodil. 2011. Introduction. In Experimental archaeology: Between enlightenment and experience . Edited by Bodil Petersson and Lars E. Narmo, 9–26. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia Series 8, no. 62. Lund, Sweden: Lund Univ.

An introduction to an edited volume on experimental archaeology within the current Scandinavian school of thought. It takes a less strictly scientific view of the field.

Reeves Flores, Jodi, and Roeland Paardekooper, eds. 2014. Experiments past: Histories of experimental archaeology . Leiden, The Netherlands: Sidestone.

Provides useful overviews of developments in Europe and makes some of the literature on these accessible in English.

Reynolds, Peter J. 1999. The nature of experiment in archaeology. In Experiment and design: Archaeological studies in honour of John Coles . Edited by Anthony F. Harding, 156–162. Oxford: Oxbow.

A very personal view of experimental archaeology by one of its most famous practitioners that maintains a very strict scientific view and provides a useful classification of experiments by type and aims.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Anthropology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Africa, Anthropology of

- Agriculture

- Animal Cultures

- Animal Ritual

- Animal Sanctuaries

- Anorexia Nervosa

- Anthropocene, The

- Anthropological Activism and Visual Ethnography

- Anthropology and Education

- Anthropology and Theology

- Anthropology, Degrowth and

- Anthropology of Islam

- Anthropology of Kurdistan

- Anthropology of the Senses

- Anthrozoology

- Antiquity, Ethnography in

- Applied Anthropology

- Archaeobotany

- Archaeologies of Sexuality

- Archaeology

- Archaeology and Political Evolution

- Archaeology and Race

- Archaeology and the Body

- Archaeology, Gender and

- Archaeology, Global

- Archaeology, Historical

- Archaeology, Indigenous

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Archaeology of the Senses

- Art Museums

- Art/Aesthetics

- Autoethnography

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bass, William M.

- Benedict, Ruth

- Binford, Lewis

- Bioarchaeology

- Biocultural Anthropology

- Biological and Physical Anthropology

- Biological Citizenship

- Boas, Franz

- Bone Histology

- Bureaucracy

- Business Anthropology

- Cargo Cults

- Charles Sanders Peirce and Anthropological Theory

- Christianity, Anthropology of

- Citizenship

- Class, Archaeology and

- Clinical Trials

- Cobb, William Montague

- Code-switching and Multilingualism

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Cole, Johnnetta

- Colonialism

- Commodities

- Consumerism

- Crapanzano, Vincent

- Cultural Heritage Presentation and Interpretation

- Cultural Heritage, Race and

- Cultural Materialism

- Cultural Relativism

- Cultural Resource Management

- Culture and Personality

- Culture, Popular

- Curatorship

- Cyber-Archaeology

- Dalit Studies

- Dance Ethnography

- de Heusch, Luc

- Deaccessioning

- Design, Anthropology and

- Digital Anthropology

- Disability and Deaf Studies and Anthropology

- Douglas, Mary

- Drake, St. Clair

- Durkheim and the Anthropology of Religion

- Economic Anthropology

- Embodied/Virtual Environments

- Emotion, Anthropology of

- Environmental Anthropology

- Environmental Justice and Indigeneity

- Ethnoarchaeology

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnographic Documentary Production

- Ethnographic Films from Iran

- Ethnography

- Ethnography Apps and Games

- Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography

- Ethnomusicology

- Ethnoscience

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E.

- Evolution, Cultural

- Evolutionary Cognitive Archaeology

- Evolutionary Theory

- Experimental Archaeology

- Federal Indian Law

- Feminist Anthropology

- Film, Ethnographic

- Forensic Anthropology

- Francophonie

- Frazer, Sir James George

- Geertz, Clifford

- Gender and Religion

- GIS and Archaeology

- Global Health

- Globalization

- Gluckman, Max

- Graphic Anthropology

- Haraway, Donna

- Healing and Religion

- Health and Social Stratification

- Health Policy, Anthropology of

- Health, Race and

- Heritage Language

- House Museums

- Human Adaptability

- Human Evolution

- Human Rights

- Human Rights Films

- Humanistic Anthropology

- Hurston, Zora Neale

- Identity Politics

- India, Masculinity, Identity

- Indigeneity

- Indigenous Boarding School Experiences

- Indigenous Economic Development

- Indigenous Media: Currents of Engagement

- Industrial Archaeology

- Institutions

- Interpretive Anthropology

- Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity

- Laboratories

- Landscape Archaeology

- Language and Emotion

- Language and Law

- Language and Media

- Language and Race

- Language and Urban Place

- Language Contact and its Sociocultural Contexts, Anthropol...

- Language Ideology

- Language Socialization

- Leakey, Louis

- Legal Anthropology

- Legal Pluralism

- Levantine Archaeology

- Liberalism, Anthropology of

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Historical

- Literary Anthropology

- Local Biologies

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude

- Malinowski, Bronisław

- Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Visual Anthropology

- Maritime Archaeology

- Material Culture

- Materiality

- Mathematical Anthropology

- Matriarchal Studies

- Mead, Margaret

- Media Anthropology

- Medical Activism

- Medical Anthropology

- Medical Technology and Technique

- Mediterranean

- Mendel, Gregor

- Mental Health and Illness

- Mesoamerican Archaeology

- Mexican Migration to the United States

- Militarism, Anthropology and

- Missionization

- Morgan, Lewis Henry

- Multimodal Ethnography

- Multispecies Ethnography

- Museum Anthropology

- Museum Education

- Museum Studies

- NAGPRA and Repatriation of Native American Human Remains a...

- Narrative in Sociocultural Studies of Language

- Nationalism

- Needham, Rodney

- Neoliberalism

- NGOs, Anthropology of

- Niche Construction

- Northwest Coast, The

- Oceania, Archaeology of

- Paleolithic Art

- Paleontology

- Performance Studies

- Performativity

- Perspectivism

- Philosophy of Museums

- Plantations

- Political Anthropology

- Postprocessual Archaeology

- Postsocialism

- Poverty, Culture of

- Primatology

- Primitivism and Race in Ethnographic Film: A Decolonial Re...

- Processual Archaeology

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Anthropology

- Public Sociocultural Anthropologies

- Religion and Post-Socialism

- Religious Conversion

- Repatriation

- Reproductive and Maternal Health in Anthropology

- Reproductive Technologies

- Rhetoric Culture Theory

- Rural Anthropology

- Sahlins, Marshall

- Sapir, Edward

- Scandinavia

- Science Studies

- Secularization

- Settler Colonialism

- Sex Estimation

- Sign Language

- Skeletal Age Estimation

- Social Anthropology (British Tradition)

- Social Movements

- Socialization

- Society for Visual Anthropology, History of

- Socio-Cultural Approaches to the Anthropology of Reproduct...

- Sociolinguistics

- Sound Ethnography

- Space and Place

- Stable Isotopes

- Stan Brakhage and Ethnographic Praxis

- Structuralism

- Studying Up

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Democracy in

- Surrealism and Anthropology

- Technological Organization

- Trans Studies in Anthroplogy

- Transhumance

- Transnationalism

- Tree-Ring Dating

- Turner, Edith L. B.

- Turner, Victor

- University Museums

- Urban Anthropology

- Virtual Ethnography

- Visual Anthropology

- Whorfian Hypothesis

- Willey, Gordon

- Wolf, Eric R.

- Writing Culture

- Youth Culture

- Zora Neale Hurston and Visual Anthropology

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

Real Archaeology

Anth 100 searches for the truth.

Experimental archaeology and its uses

Figure 1: Metal working in the Museo Archeologico Etnologico in Modena. Photo by Andrea Moretti. https://exarc.net/issue-2019-1/ea/experimental-archaeology-who-does-it-what-use

Experimental archaeology is defined as a sub-field of archaeology research that uses many strategies to imitate past events and attempt to better understand what happened (Paardekooper 2019). While experimental archaeology does have its limits in not working with real artifacts, it does have the unique advantage of attempting to repeat the processes that occurred in the past and gain knowledge through data and experience.

Traditionally, this sub-field was one of the aspects of archaeology that is conducted scientifically by developing a hypothesis, conducting an experiment, and then analyzing the data to come to a conclusion. However, experimental archaeology has grown and taken on many forms now, such as being used as an outreach program. For example, researchers at the Stonehenge Visitor Center replicated a possible version of the creation of Stonehenge using wooden logs, ropes, simple mechanics, and community participation (Archaeology 2018) (Figure 2). Through this experiment, more questions about the creation of Stonehenge were developed, such as what were the environmental conditions when it was built? Researchers speculated that it could have been done when the ground was dry and hard, or the people may have dug the topsoil off to reach the hard and compact dirt. These hands-on experiences help inform the public of the importance of archaeology, while also bringing forth new research questions.

Figure 2: Imitating possible strategy for moving stones at Stonehenge Visitor Center. Photo by the English Heritage. https://the-past.com/feature/experimental-archaeology-at-stonehenge/

Another example of experimental archaeology is the Butser Ancient Farm. The goal of this site is to study the agricultural and economic aspects of England during the period of 400 BC to 400 AD (Stone and Planel 1999). To better understand this topic, specific research programs cover different topics, such as experimental earthwork. Experimental earthwork is the study of replicating structures made from soil such as ditches, banks, and canals (Shaw 2007). In this specific study, a set of ditches and banks were recreated to see how they were effected by environmental conditions over intervals of four, seven, and ten years (Shaw 2007). Through this type of study, researchers can further understand how different layers of soil erode and settle over time. This allows them to identify what they are observing at a genuine site. Another benefit when modeling earthworks is understanding how artifacts are preserved in certain soil conditions. Through this work, archaeologists can recognize how much time it takes for certain materials to degrade and how quickly they need to excavate certain sites to preserve artifacts.

Experimental archaeology has evolved to take on different forms with each having an important purpose. From social outreach programs to scientific studies, experimental archaeology is allowing archaeologists to better understand what they find and show the public the importance of their work.

Links of interest

https://exarc.net/issue-2013-3/ea/living-conditions-and-indoor-air-quality-reconstructed-viking-house

https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/nexus1492/news/start-of-reconstruction-indigenous-village-in-st.-vincent

Archaeology, Current. 2018. “Like a Rolling Stone: Experimental Archaeology at

Stonehenge | The Past.” The Past. June 29, 2018. https://the-

past.com/feature/experimental-archaeology-at-stonehenge/.

Paardekooper, Roeland. 2019. “Experimental Archaeology: Who Does It, What Is the

Use?” EXARC Journal , no. EXARC Journal Issue 2019/1 (February).

https://exarc.net/issue-2019-1/ea/experimental-archaeology-who-does-it-

what-use.

Shaw, Christine. 2007. “Site Publications.” Butser Ancient Farm Archive. 2007.

http://www.butser.org.uk/sitepubs.html.

Stone, Edited Peter G, and Phillippe G Planel. 1999. “A Unique Research & Educational

Establishment,” 10.

1 thought on “ Experimental archaeology and its uses ”

To what degree are experimental archaeology and public archaeology related? Do they intersect?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Protected by Akismet | Blog with WordPress

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Experimental archaeology, quick reference.

A branch of archaeological investigation in which carefully controlled experiments are undertaken in order to provide data and insights that aid in the interpretation of the archaeological record. These experiments vary widely in their nature and purpose. Some, such as the creation and monitoring of experimental earthworks to see how they decay, are long‐lived and massive in scale. Others, such as the reproduction of ancient tools to learn about the processes of manufacture, may take a matter of hours or days.

From: experimental archaeology in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology »

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'experimental Archaeology' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 19 December 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

Character limit 500 /500

study guides for every class

That actually explain what's on your next test, experimental archaeology, from class:, intro to archaeology.

Experimental archaeology is a research approach that involves recreating past human behaviors, techniques, and processes to better understand how ancient peoples lived and interacted with their environment. By using controlled experiments, researchers can test hypotheses about artifacts and archaeological sites, providing insights into the technologies, materials, and skills of past cultures.

congrats on reading the definition of experimental archaeology . now let's actually learn it.

5 Must Know Facts For Your Next Test

- Experimental archaeology helps archaeologists validate their interpretations by directly testing the functionality of artifacts and tools.

- This approach can include a wide range of activities, from reconstructing ancient buildings to creating pottery or stone tools using traditional methods.

- The findings from experimental archaeology can reveal insights into the social and cultural practices of ancient societies that may not be evident from artifacts alone.

- Researchers often collaborate with craftspeople or indigenous groups to ensure authenticity in their experiments, leading to more accurate representations of historical techniques.

- Experimental archaeology has become increasingly important in addressing questions about technological evolution and adaptation in response to environmental changes.

Review Questions

- Experimental archaeology allows researchers to recreate and test ancient technologies and practices, providing direct insights into how past cultures operated. By conducting controlled experiments, archaeologists can better understand the functionality of artifacts, which can lead to new interpretations of how people interacted with their environment. This hands-on approach helps bridge gaps in knowledge by demonstrating practical applications of ancient skills and materials.

- Ethnoarchaeology plays a crucial role in experimental archaeology by providing contemporary analogs for understanding ancient behaviors. By studying modern societies and their material culture, researchers can gain insights into how similar technologies might have been used in the past. This comparative approach enriches experimental archaeology by allowing for more informed hypotheses and interpretations based on observed practices that reflect historical contexts.

- Experimental archaeology significantly impacts archaeological interpretation by providing empirical evidence that can support or challenge existing theories about past human behavior. By actively engaging in recreative processes, researchers uncover insights into technology, economy, and social structures that might be overlooked when relying solely on artifacts. This empirical approach enhances our understanding of how ancient societies functioned, adapted, and evolved over time, making it an essential tool for reconstructing human history.

Related terms

Replicative Experimentation : A method within experimental archaeology where researchers create exact replicas of artifacts or structures to study their use and production techniques.

Ethnoarchaeology : The study of contemporary societies to understand the relationship between human behavior and material culture, helping to inform interpretations of archaeological finds.

Field Experiments : Experiments conducted in real-world settings that mimic ancient environments or conditions to observe how past peoples might have operated.

" Experimental archaeology " also found in:

Subjects ( 5 ).

- Archaeology and Museums

- Archaeology of the Holy Land

- Great Discoveries in Archaeology

- Intro to Paleoanthropology

- World Prehistory

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you personalised advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy and cookie policy

- Centre for Archaeological Science

- Research themes

Experimental Archaeology

What is experimental archaeology.

As archaeologists, we study the culture and lifeways of ancient people. However, because culture does not preserve, archaeologists have to reconstruct past behaviours from material remains. To do this, archaeologists conduct experiments to evaluate the range of activities that may have taken place in the past. These experiments can range from the making and using of Palaeolithic stone tools to reconstructing prehistoric houses, transporting megalithic structures, and ocean voyaging. By replicating these ancient activities, researchers can generate and test ideas about the technology and knowledge of past people.

What does an Experimental Archaeologist do?

Archaeological experiments often take the form of replicating ancient structures or artefacts using materials, tools and techniques that were possibly used by past people. This form of experimentation has been referred to as ‘replicative’ or ‘actualistic’ experiment because the focus is placed on the consistent replication of archaeological remains. More recently, archaeologists have emphasised the use of a scientific framework for archaeological experimentation, where a greater focus is placed on the design and control of experiments for testing specific hypotheses about past activities.

What do we do at CAS?

CAS has a dedicated experimental laboratory for stone tool experimental research. Here, CAS researchers employ both flintknapping and controlled flaking to understand prehistoric stone tools. In particular, CAS houses a custom-built, mechanical flaking machine (‘Rogi’) that can simulate the stone flaking process under a controlled setting. In this way, CAS researchers are able to isolate and quantify the influence of specific knapping parameters, such as the shape of the core, the shape and material of the hammer, and the angle and location of the hammer impact. These fundamental properties, once verified experimentally, can be effectively applied to archaeological data to understanding change in past stone knapping techniques. Another focus of the CAS experimental laboratory is to evaluate the effect of heat treatment on different stone types. By using the mechanical flaking machine and a dedicated oven furnace, current CAS projects are examining the influence of source variation and heating temperature on the flaking properties of siliceous raw material from Australia, South Africa and Indonesia.

To expand the scope of our experimental research at CAS, we collaborate with other researchers in Geology and Engineering at the University of Wollongong to better characterise the mechanical properties of archaeological materials. This includes applying techniques such as petrographic analysis, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray florescence/diffraction, and hardness testing to understand how different physical characteristics may have influenced the technological decisions and strategies of ancient people.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Experimental tree felling with reconstructed adzes of the Linear Pottery culture for the analysis of stress marks on the adze blades and ghost lines on the tree stump and the timber in comparison with marks on archaeological finds Creating a wall of mud in the Viking style.. Experimental archaeology (also called experiment archaeology) is a field of study which attempts to generate and test ...

A recent definition as stated by Mathieu (2002, 1) states experimental archaeology to be: "a sub-field of archaeological research which employs a number of different methods, techniques, analyses, and approaches within the context of a controllable imitative experiment to replicate past phenomena (from objects to systems) in order to generate ...

Experimental Archaeology is an approach for filling gaps in our knowledge about the past, which cannot be filled through other archaeological research methods. An archaeological experiment must always answer a specific research question through practically testing production, use and/or formation of material culture and/or archaeological ...

experimental archaeology as science. Having put forward a definition of experimentation, however, it is still not entirely clear what 'experimental archaeology' exactly means. If experiment is the mainstay of modern science, then, strictly speaking, is there really any difference between 'experimental archaeology' and 'archaeological science'?

Summary. Scientific definitions of "experimental archaeology" emphasize key words such as exploring, testing, and imitation. Archaeological data and observations are key elements in experiments, whether the researcher is testing hypotheses derived from archaeological deposits or objects, innovative approaches to documentation and excavation, or the formation of and post-depositional ...

Experimental archaeology is a multifaceted approach employed by a wide and rapidly expanding range of exponents including everybody from lab-based archaeological research scientists through to museum professionals and re-enactment groups. Scientific experiments are trials designed to test a hypothesis which will either be rejected (falsified ...

Experimental archaeology is defined as a sub-field of archaeology research that uses many strategies to imitate past events and attempt to better understand what happened (Paardekooper 2019). While experimental archaeology does have its limits in not working with real artifacts, it does have the unique advantage of attempting to repeat the ...

experimental Archaeology. Quick Reference [Ge] A branch of archaeological investigation in which carefully controlled experiments are undertaken in order to provide data and insights that aid in the interpretation of the archaeological record. These experiments vary widely in their nature and purpose. Some, such as the creation and monitoring ...

Definition. Experimental archaeology is a research approach that involves recreating past human behaviors, techniques, and processes to better understand how ancient peoples lived and interacted with their environment. By using controlled experiments, researchers can test hypotheses about artifacts and archaeological sites, providing insights ...

What does an Experimental Archaeologist do? Archaeological experiments often take the form of replicating ancient structures or artefacts using materials, tools and techniques that were possibly used by past people. This form of experimentation has been referred to as 'replicative' or 'actualistic' experiment because the focus is placed ...