12 Photo Essays Highlight the Heroes and Heartaches of the Pandemic

Pictures piece together a year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photos: One Year of Pandemic

Getty Images

A boy swims along the Yangtze river on June 30, 2020 in Wuhan, China.

A year has passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March, 11, 2020. A virus not visible to the human eye has left its mark in every corner of the world. No single image can define the loss and heartache of millions of global citizens, but photojournalists were there to document the times as best they could. From the exhaustion on the faces of frontline medical workers to vacant streets once bustling with life, here is a look back at photo essays published by U.S. News photo editors from the past year. When seen collectively, these galleries stitch together a year unlike any other.

In January of 2020, empty streets, protective masks and makeshift hospital beds became the new normal in Wuhan, a metropolis usually bustling with more people than New York City. Chinese authorities suspended flights, trains and public transportation, preventing locals from leaving the area, and placing a city of 11 million people under lockdown. The mass quarantine invokes surreal scenes and a grim forecast.

Photos: The Epicenter of Coronavirus

Photojournalist Krisanne Johnson documented New Yorkers in early March of 2020, during moments of isolation as a climate of uncertainty and tension hung over the city that never sleeps.

Coronavirus in NYC Causes Uncertainty

For millions of Italians, and millions more around the globe, the confines of home became the new reality in fighting the spread of the coronavirus. Italian photojournalist Camila Ferrari offered a visual diary of intimacy within isolation.

Photos: Confined to Home in Milan

Around the world, we saw doctors, nurses and medical staff on the front lines in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photos: Hospitals Fighting Coronavirus

As the pandemic raged, global citizens found new ways of socializing and supporting each other. From dance classes to church services, the screen took center stage.

Photos: Staying Connected in Quarantine

In April of 2020, photographer John Moore captured behind the scene moments of medical workers providing emergency services to patients with COVID-19 symptoms in New York City and surrounding areas.

Photos: Paramedics on the Front Lines

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted undocumented communities that often lack unemployment protections, health insurance and at times, fear deportation.

Photos: Migrants and the Coronavirus

Aerial views showed startlingly desolate landscapes and revealed the scale of the pandemic.

Photos: COVID-19 From Above

With devastating death tolls, COVID-19 altered the rituals of mourning loved ones.

Photos: Final Farewells

In recognition of May Day in 2020, these portraits celebrated essential workers around the globe.

Photos: Essential Workers of the World

In May 2020, of the 10 counties with the highest death rates per capita in America, half were in rural southwest Georgia, where there are no packed apartment buildings or subways. And where you could see ambulances rushing along country roads, just fields and farms in either direction, carrying COVID-19 patients to the nearest hospital, which for some is an hour away.

Photos: In Rural Georgia, Devastation

In January of 2021, as new variants of the virus emerged, Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and other vaccines led a historic global immunization rollout, offering hope.

Photos: COVID-19 Vaccinations

Join the Conversation

Tags: Coronavirus , public health , Photo Galleries , New York City , pandemic

U.S. News Decision Points

Your trusted source for the latest news delivered weekdays from the team at U.S. News and World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Nov. 11, 2024

The Best Cartoons on Donald Trump

Nov. 27, 2024, at 11:36 a.m.

Trump’s 2024 Campaign in Photos

Nov. 6, 2024

The Costliest of the 2024 Hurricanes

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder Nov. 29, 2024

Trump’s Space Plans: 5 Things to Know

Emma McSpadden Nov. 29, 2024

Democratic Presidential Maybes in 2028

Elliott Davis Jr. Nov. 29, 2024

Project 2025: What to Know Now

Laura Mannweiler Nov. 27, 2024

What Is a Tariff and Who Pays It?

Tim Smart Nov. 27, 2024

How Much Will Thanksgiving Dinner Cost?

Inflation Ticks Up, Economy Strong

Coronavirus

COVID-19 photo essay reflects on the day our lives changed forever three years ago

By Kate Christian

Topic: COVID-19

The pandemic changed people's lives in ways that were previously unthinkable. ( ABC News: Andrew O'Connor )

While it feels almost a lifetime ago for some, it's been exactly three years since a state of emergency was declared in Western Australia as the novel coronavirus began to send shock waves around the world.

Already isolated by its geography, the unprecedented move cemented the state as a hermit kingdom and fundamentally changed the way sandgropers went about their daily lives.

This picture essay illustrates a pivotal and unsettling chapter in our history, and reflects how the virus dictated the way we lived.

Panic and confusion

COVID-19 was first detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019, but the panic didn't set in until a couple of months later when news of mass deaths overseas was beamed in to living rooms across Australia.

The virus captivated the entire world, but the threat really hit home when Australia recorded its first COVID death on March 1 — a Perth man who had been aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship.

Australians were given a stern warning to return home as soon as possible ahead of the country's border being slammed shut, with international arrivals forced into hotel quarantine in an effort to stop the deadly virus getting in.

The first round of COVID-19 restrictions, including gathering limits and indoor venue closures, started to give people an inkling of how much their lives were about to be turned upside down.

Holidays and big events were cancelled, weddings went online and Rottnest Island went from the home of quokka selfies to a quarantine hub for cruise ship passengers.

Lines curled around liquor stores as the fear of being locked down without a cold stubbie or red wine in hand was too much to bear for most, while subscriptions to streaming services went through the roof.

Grocery store shelves were stripped bare and arguments broke out in supermarket aisles as panic buying led to a nationwide toilet paper drought.

ABC reporter Francesca Mann dared to dream when she saw a shopper walk past her with the rare commodity at a Geraldton supermarket.

"I could not believe my eyes," she said.

"I quickly walked over to the toilet paper aisle and there were about seven packs left. It felt like the most valuable item at the time, so it got the royal treatment on the way home."

Mann snapped an equally humorous shot of her pet cat Arya sprawled across her desk in the first few days of working from home.

'Stop the spread'

The state introduced its first round of border restrictions at the end of March, restricting interstate travel to stop the virus spreading between regions and to protect vulnerable Indigenous communities.

On April 5, 2020, the WA government implemented its harshest border restrictions yet, slamming its borders shut — not just to international arrivals, but to the east as well.

It marked the beginning of an upsetting chapter in the state's history, leaving families divided for two years and living up to Premier Mark McGowan's promise to turn WA into an "island within an island".

The travel restrictions wreaked havoc on the tourism and events industries, but it also created a spike in domestic tourism when the state eased restrictions to allow West Australians to holiday in their own backyard.

Sandgropers swapped their annual pilgrimage to Bali for the sublime sunsets in Broome, the chance to swim with whale sharks in Exmouth or to see the ancient gorges in the Karijini National Park.

But Perth's bustling city centre had turned into a ghost town as West Australians dutifully obeyed restrictions, which shut down the city.

Just a few pedestrians could be spotted in Forrest Place in April, 2020. Image: Hugh Sando.

Even a trip to the beach came with reminders to practise social distancing. Image: Amelia Searson.

Trains crisscrossed the city virtually empty. Image: Hugh Sando.

The doors to restaurants, cafes and bars were shuttered. Image: Rebecca Mansell.

The state library was eerily empty. Image: Emma Wynne.

Children were cooped up inside as playgrounds closed. Image: Gian De Poloni.

Slogans like this started popping up around Perth as people banded together to face the crisis. Image: Damian Smith.

For weeks, the cruise ship Artania became the focus of a tense stand-off between the operator and Mr McGowan, who demanded it leave WA waters.

Anzac Day that year was unlike any other due to the traditional service and march being cancelled — the first time since 1942.

Veterans and families instead marked Anzac Day from the end of their suburban driveways.

By this stage, the virus dominated every aspect of our lives.

Even the security guard, Steve, who opened the door for the premier before he delivered his daily press conference, had become part of life under COVID.

Living inside the bubble

Restrictions were gradually eased in May after the virus was eliminated, allowing West Australians to continue living relatively normally for many months compared to what was happening over east.

With no community transmission, WA moved from a hard border to a controlled border in October, with authorities continually lowering and lifting the drawbridge in line with outbreaks in other states.

On December 5, a tool was unveiled that would dramatically change the way West Australians interacted with the world around them.

The trio of snap lockdowns

But it was impossible to keep the virus out forever, with the state's 10-month coronavirus-free streak ending on January 21, 2021 when a hotel quarantine security guard tested positive.

Perth was locked down twice more in 2021 — from April 24 to April 27 after a hotel quarantine outbreak and from June 29 to July 3 after three COVID cases were detected in the community.

Vaccine hesitancy takes hold

In October, one of the most divisive policies in WA's history was announced — mandatory vaccination for 75 per cent of the state's workforce.

Some were concerned about potential health impacts from the vaccine and felt it was impinging on people's right to have autonomy over their own bodies, while others felt it was the only way to reopen the borders and protect people from the virus.

When the double-dose vaccination rate reached 80 per cent in December, it was announced that WA would finally reopen its border to the rest of the world on February 5, 2022.

But the joy that rippled through the community was short-lived, with WA Premier Mark McGowan performing a sensational backflip just a few weeks later at a late night press conference when he announced the reopening would be delayed.

However, it turned out the virulent strain was circulating in the community anyway, and the virus started to spread significantly for the first time in two years.

'Let it rip'

On February 18, Mr McGowan made the announcement many had been waiting for — WA's hard border would come down on March 3 as he conceded it was no longer possible to stop the spread of the virus.

Many employers, including ABC News in Perth, quickly reverted to working from home arrangements for all but operationally critical staff to minimise the risk of spreading the virus in the workplace.

As case numbers grew, so too did tensions between the state government and peak medical groups that warned against easing restrictions, as cracks in the hospital system deepened.

After being on the frontline of the battle against COVID, health workers began rallying for better pay, which would eventually lead to full-scale industrial action.

As vaccination rates rose and the COVID outbreak in WA eased in April, the McGowan Government lifted most mask-wearing requirements but the Perth CBD remained a ghost town.

Most remaining restrictions were removed in May as the triple-dose vaccination rate hit 80 per cent, but many vulnerable West Australians chose to stay home to shield themselves from the virus.

But COVID continued to fade into the background for most, as the things that derailed our lives — lockdowns, mandatory isolation, mask and vaccine mandates— gradually became distant memories.

Living with the virus

People have learned how to live with the virus, and getting the vaccine has become about as normal as getting a yearly flu jab.

After 963 days, WA's state of emergency finally ended on November 4, but the heartache caused by the 956 people who lost their lives, and the far-reaching impact on society and people's livelihoods, will be felt for years to come.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related stories

Three years into the pandemic, it's clear covid won't fix itself. here's what we need to focus on next.

Topic: Analysis

When I caught COVID, I thought I'd get back to normal. I was wrong

Take a look at life behind WA's hard border if you want to see a post-COVID world

Related topics

State and Territory Government

Search the United Nations

- Policy and Funding

- Recover Better

- Disability Inclusion

- Secretary-General

- Financing for Development

- ACT-Accelerator

- Member States

- Health and Wellbeing

- Policy and Guidance

- Vaccination

- COVID-19 Medevac

- i-Seek (requires login)

- Awake at Night podcast

COVID-19 photo essay: We’re all in this together

About the author, department of global communications.

The United Nations Department of Global Communications (DGC) promotes global awareness and understanding of the work of the United Nations.

23 June 2020 – The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the interconnected nature of our world – and that no one is safe until everyone is safe. Only by acting in solidarity can communities save lives and overcome the devastating socio-economic impacts of the virus. In partnership with the United Nations, people around the world are showing acts of humanity, inspiring hope for a better future.

Everyone can do something

Rauf Salem, a volunteer, instructs children on the right way to wash their hands, in Sana'a, Yemen. Simple measures, such as maintaining physical distance, washing hands frequently and wearing a mask are imperative if the fight against COVID-19 is to be won. Photo: UNICEF/UNI341697

Creating hope

Venezuelan refugee Juan Batista Ramos, 69, plays guitar in front of a mural he painted at the Tancredo Neves temporary shelter in Boa Vista, Brazil to help lift COVID-19 quarantine blues. “Now, everywhere you look you will see a landscape to remind us that there is beauty in the world,” he says. Ramos is among the many artists around the world using the power of culture to inspire hope and solidarity during the pandemic. Photo: UNHCR/Allana Ferreira

Inclusive solutions

Wendy Schellemans, an education assistant at the Royal Woluwe Institute in Brussels, models a transparent face mask designed to help the hard of hearing. The United Nations and partners are working to ensure that responses to COVID-19 leave no one behind. Photo courtesy of Royal Woluwe Institute

Humanity at its best

Maryna, a community worker at the Arts Centre for Children and Youth in Chasiv Yar village, Ukraine, makes face masks on a sewing machine donated by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and civil society partner, Proliska. She is among the many people around the world who are voluntarily addressing the shortage of masks on the market. Photo: UNHCR/Artem Hetman

Keep future leaders learning

A mother helps her daughter Ange, 8, take classes on television at home in Man, Côte d'Ivoire. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, caregivers and educators have responded in stride and have been instrumental in finding ways to keep children learning. In Côte d'Ivoire, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) partnered with the Ministry of Education on a ‘school at home’ initiative, which includes taping lessons to be aired on national TV and radio. Ange says: “I like to study at home. My mum is a teacher and helps me a lot. Of course, I miss my friends, but I can sleep a bit longer in the morning. Later I want to become a lawyer or judge." Photo: UNICEF/UNI320749

Global solidarity

People in Nigeria’s Lagos State simulate sneezing into their elbows during a coronavirus prevention campaign. Many African countries do not have strong health care systems. “Global solidarity with Africa is an imperative – now and for recovering better,” said United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. “Ending the pandemic in Africa is essential for ending it across the world.” Photo: UNICEF Nigeria/2020/Ojo

A new way of working

Henri Abued Manzano, a tour guide at the United Nations Information Service (UNIS) in Vienna, speaks from his apartment. COVID-19 upended the way people work, but they can be creative while in quarantine. “We quickly decided that if visitors can’t come to us, we will have to come to them,” says Johanna Kleinert, Chief of the UNIS Visitors Service in Vienna. Photo courtesy of Kevin Kühn

Life goes on

Hundreds of millions of babies are expected to be born during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fionn, son of Chloe O'Doherty and her husband Patrick, is among them. The couple says: “It's all over. We did it. Brought life into the world at a time when everything is so uncertain. The relief and love are palpable. Nothing else matters.” Photo: UNICEF/UNI321984/Bopape

Putting meals on the table

Sudanese refugee Halima, in Tripoli, Libya, says food assistance is making her life better. COVID-19 is exacerbating the existing hunger crisis. Globally, 6 million more people could be pushed into extreme poverty unless the international community acts now. United Nations aid agencies are appealing for more funding to reach vulnerable populations. Photo: UNHCR

Supporting the frontlines

The United Nations Air Service, run by the World Food Programme (WFP), distributes protective gear donated by the Jack Ma Foundation and Alibaba Group, in Somalia. The United Nations is using its supply chain capacity to rapidly move badly needed personal protective equipment, such as medical masks, gloves, gowns and face-shields to the frontline of the battle against COVID-19. Photo: WFP/Jama Hassan

S7-Episode 2: Bringing Health to the World

“You see, we're not doing this work to make ourselves feel better. That sort of conventional notion of what a do-gooder is. We're doing this work because we are totally convinced that it's not necessary in today's wealthy world for so many people to be experiencing discomfort, for so many people to be experiencing hardship, for so many people to have their lives and their livelihoods imperiled.”

Dr. David Nabarro has dedicated his life to global health. After a long career that’s taken him from the horrors of war torn Iraq, to the devastating aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami, he is still spurred to action by the tremendous inequalities in global access to medical care.

“The thing that keeps me awake most at night is the rampant inequities in our world…We see an awful lot of needless suffering.”

:: David Nabarro interviewed by Melissa Fleming

Brazilian ballet pirouettes during pandemic

Ballet Manguinhos, named for its favela in Rio de Janeiro, returns to the stage after a long absence during the COVID-19 pandemic. It counts 250 children and teenagers from the favela as its performers. The ballet group provides social support in a community where poverty, hunger and teen pregnancy are constant issues.

Radio journalist gives the facts on COVID-19 in Uzbekistan

The pandemic has put many people to the test, and journalists are no exception. Coronavirus has waged war not only against people's lives and well-being but has also spawned countless hoaxes and scientific falsehoods.

Life, emptiness and resolve: A photo essay on the pandemic’s toll along Pico Boulevard

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Los Angeles imposed coronavirus restrictions on restaurants, bars, gyms and other businesses on March 15, 2020. It was the beginning of a year of loss, upheaval and constant adaptation. Public health rules kept evolving. Relief programs brought help for some but only red tape for others. Supply chains were a mess. There were shoppers who feared even entering stores and customers who crowded newly built patios. Some businesses cut hours, services and staff, or shut down. Many have survived beyond their expectations. Staff photographer Genaro Molina shows us how much Pico Boulevard has changed one year later.

“We are deeply grateful for the support we have received during these unprecedented times & throughout the 10 plus years we have been in business. It is with great sadness that due to the continuing challenges of the pandemic for our industry we have made the difficult decision to close.”

— Statement on website for Westside Tavern

“(The) pandemic has greatly effected our business.”

— Robert Oliver, sign spinner at Liberty Tax Service

“Now it’s worse than last year.”

— Laura Peres at Dana Accesorios in the Garment District

“We are collectively feeling the loss. So I think just collectively mourning and acknowledging it provides a level of healing that is hard to translate into words.”

— Karla Funderburk, whose gallery has received 60,000 from 45 states and nine countries from as far away as Tibet.

“2020 felt like our year. We blew up on social media. The abrupt halt was the hardest part for me,”

— Angela Guison, manager of Rave Wonderland

When the doors of Botanica Luz del Día were closed early on in the pandemic, customers couldn’t browse for their preferred veladoras or stop into the Pico-Union store for tarot readings. The shop went online and sales rebounded. “The website is booming right now,” said Anthony Ponce, grandson of the owner.

“Concerts went to zero. Lessons dropped to 5% of what it was. We’re seeing a lot of repair business from people who are stuck at home and want to play. Consignments are up a lot.”

— Walt McGraw, who has been running the 63-year-old shop with his wife, Nora, since her parents’ retirement.

More visual journalism from the Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Roscoe’s House of Chicken ‘n Waffles closes its Pico location after 32 years

L.A.’s love of sprawl made it America’s most overcrowded place. Poor people pay a deadly price

L.A. County won’t impose new mask mandate as coronavirus cases decline

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Genaro Molina is an award-winning staff photographer for the Los Angeles Times. He has worked in journalism for more than 35 years starting at the San Francisco Chronicle. Molina has photographed the life and death of Pope John Paul II, the tragedy of AIDS in Africa, the impact of Hurricane Katrina, and Cuba after Castro. His work has appeared in nine books and his photographs have been exhibited extensively including at the Smithsonian Institute and the Annenberg Space for Photography.

More From the Los Angeles Times

World & Nation

Trump picks Jay Bhattacharya, critic of COVID mandates, to lead National Institutes of Health

Opinion: Don’t be stupid: Skipping your COVID booster could reduce your IQ

California’s COVID surge is finally over. But expect another spike in the coming months

Science & Medicine

Depression was rising among young people in Southern California. COVID made it worse

Most read in california.

Walmart worker goes in for an extra shift and walks out a millionaire

Newsom tries to redefine the California-vs.-Trump narrative

Member of prominent Rothschild family found dead after Laurel Canyon house fire, neighbors say

Sunday marks the 92nd anniversary of the Hollywood Christmas Parade

The Year of Endurance

Hope and uncertainty amid a pandemic that wouldn’t end.

In 2021, the pandemic forced us all to think hard about who we do and don’t trust

Introduction by david rowell.

As a nation, we are supposed to be built around trust. Look at the back of the bills in your wallet. “In God We Trust.”

Trust the system.

Trust yourself.

Trust but verify.

Trust your instincts.

Love may be the emotion we like to think ultimately propels us, but it’s trust that informs how we go about our daily lives. And yet. Our level of trust, our very foundation, has been crumbling for a long time now. Scandals, abuse and corruption in the major pillars of our society — religious institutions, education, business, military, government, health care, law enforcement, even the sports world — have made us a wary people.

When the pandemic came, first as murmurs that were easy to tune out, then as an unbounded crisis we couldn’t tune into enough, our relationship to trust was newly infected with something we didn’t fully understand. And before long, who and what we trusted — or didn’t — in the form of elected leaders, scientists and doctors became one more cause of death here and all over the world. In this way, distrust was a kind of pandemic itself: widely contagious and passed by the mouth.

As the first American casualties of covid-19 were announced, President Trump kept insisting it would disappear “with the heat” or “at the end of the month” or “without a vaccine.” Like a disgraced, fringe science teacher, he entertained this idea at one coronavirus news conference: “I see the disinfectant that knocks it out in a minute, one minute. And is there a way we can do something like that by injection inside, or almost a cleaning?” With leadership like this, the country was receiving an injection — of chaos.

The pandemic ripped through the rest of 2020, and America was not only more splintered than ever, but also a dangerous place to be. Some politicians declared to the public, “I trust the science,” as if that were an unprecedented and heroic stance.

As we navigated our way into 2021, questions about what to believe led — painfully and predictably — to doubts about the most reliable way we had to stay safe: wearing masks. With the return to schools looming, the debate about masks and children — masks as protectors, or masks as educational folly — played out like a plague of rants. No one seemed to trust others to do the right thing anymore, whatever that was. By summer’s end, trust felt like the latest variant to avoid.

Trust takes lots of forms, but can we actually see it in a photograph the way we can identify a cloud or a wave, or an overt moment of joy or sadness? The photo essays that follow capture a full tableau of human responses in year two of the pandemic — trepidation, but also a sense of renewal; celebration, but caution as well. And despite rancor and confusion still being in as steady supply as the vaccine itself, the permutations of trust have their own presence here, too, if we’re open enough to seeing them.

When Jay Wescott went on tour with rock band Candlebox, he was documenting one of the many performing acts that returned to the road this summer, after the long hiatus. On tour there’s a lot variables you can control, and just as many, if not more, that you can’t — and in the time of covid, control and trust form their own essential but perilous interplay. The picture of the band’s drummer, Robin Diaz, who is vaccinated but unmasked, setting up his kit in such proximity to road manager Carlos Novais, vaccinated and masked, not only captures that still-odd dynamic that goes into making any live performance happen right now; it is also a welcome contrast to all the images of masked and unmasked protesters screaming at each other about what and whom to trust. On tour with Candlebox, Westcott observed how trust is carrying the band forward, creating harmonies on and off the stage.

Much farther away, in Michael Robinson Chavez’s pictures from Sicily, we bear witness to religious celebrations as part of saint’s days, which were canceled last year because of the pandemic. The celebrations resumed, though stripped down, this September, with vaccines readily available, but then, as Chavez notes, the people of Sicily were vaccinated at lower numbers than those in other regions of the country. In one image, we see a tuba player, his mask down below his chin as he blows his notes out into the world. Behind him are masked adults and maskless children. And, perhaps all through the festival, a trust in God to watch over them.

Lucía Vázquez trained her lens on the eager crowds of young women who descended upon Miami, a city known for its own style of carnival-type celebrations, though decidedly less holy ones. These women have left masks out of their outfits and are trusting something not quite scientific and not quite political, but more personal: their guts. Such a calculation comes down to a conviction that either you won’t get the coronavirus, or, if you do, you’ll survive. It means placing a lot of trust in yourself.

As a visual meditation, the pictures in this issue offer a portrait of a historical moment in which trust and distrust have defined us. Ultimately, the photographs that follow, reflecting various realities of the pandemic, are tinted with hope that we can reclaim our lives. Not exactly as they were in the past, but in a way that still resembles how we had once imagined them for the future. These images remind us that even in our fractured, confused and suffering world, it remains possible that where we can find trust again, we can be healed.

Ready to Rock

Unmasked fans and mayflies: on tour with the band candlebox, text and photographs by jay westcott.

I n February 2020, after a dear friend passed away (not from covid), all I could think about was getting on the road with a band so I could lose myself in the work and create something that would bring joy to people. The world had other plans, though.

Sixteen months later, I headed out on tour with Candlebox. Almost 30 years has passed since the Seattle hard-rock group released its debut album and saw it sell more than 4 million copies. Frontman Kevin Martin and his current lineup invited me along to document the first part of their tour. I packed up my gear, drove west, and met the band at Soundcheck, a rehearsal and gear storage facility in Nashville, as they prepared for the tour.

Whenever people learn that I photograph musicians, inevitably they ask me what it’s like on a tour bus. I tell people it’s like camping with your co-workers from the office where you all sleep in the same tent. For weeks on end. That sours their midlife fantasies about digging out that guitar from the garage and hitting the road to become a rock star.

The people who do tour and play music, build the sets, mix the sound, sell the merch and lug the gear night after night are some of the hardest-working people I’ve ever met. They are a special breed of artists, deep thinkers, poets, masters of their instruments. Music has the ability to make you move and stop you in your tracks, to change your mood, make you smile, cry, think. The goal is the same: Put on a great show. Every night. Play like it could be your last show.

It’s easy to sit back and armchair quarterback on social media about the risks of holding festivals and rock concerts amid the pandemic, but this is what people do for a living. Few people buy albums or CDs or even download music anymore. It’s all about streaming and grabbing viewers on social media now. Touring and merch sales are about the only way musicians have to make money these days. Music is meant to be performed in front of people, a shared experience. With everybody on the bus vaccinated and ready to go, we headed to Louisville for the first of a 49-show run.

The crowd of mostly older millennials and GenXers were ready for a rock show. They knew all the words to the hits in the set — especially Candlebox’s mega-hit from the ’90s, “Far Behind” — and were into the band’s new songs too. It felt good. Then came the mayflies, in massive swarms.

The next stop on the tour was a festival along the Mississippi River in Iowa. I was up early, and as soon as we pulled in you could see mayflies dancing in the air all around us. As the day wore on, the flies intensified, and by nightfall any kind of light revealed hundreds upon hundreds of them, dancing in their own way like the crowd of unmasked fans below them. Also there were Confederate flags everywhere. Boats tied together on the river flew Trump flags in the warm summer breeze.

I was asleep when we crossed the river and made our way to St. Louis, the third stop on the tour and my last with the band. A great crowd: Close your eyes and you can easily picture yourself at Woodstock ’94. But it’s 2021 and Kevin Martin and company are still here.

Jay Westcott is a photographer in Arlington.

‘He Gave Me Life’

A cuban single mother reflects on isolation with her son, text and photographs by natalia favre.

S ingle mother Ara Santana Romero, 30, and her 11-year-old son, Camilo, have spent the past year and a half practically isolated in their Havana apartment. Just before the pandemic started, Camilo had achieved his biggest dream, getting accepted into music school. Two weeks after classes began, the schools closed and his classes were only televised. A return to the classroom was expected for mid-November, at which point all the children were scheduled to be vaccinated. According to a UNICEF analysis, since the beginning of the pandemic, 139 million children around the world have lived under compulsory home confinement for at least nine months.

Before the pandemic, Ara had undertaken several projects organizing literary events for students. After Havana went into quarantine and Camilo had to stay home, her days consisted mainly of getting food, looking after her son and doing housework. As a single mother with no help, she has put aside her wishes and aspirations. But Ara told me she never regretted having her son: “He gave me life.”

Natalia Favre is a photographer based in Havana.

Life After War in Gaza

A healing period of picnics, weddings and vaccinations, text and photographs by salwan georges.

A s I went from Israel into the Gaza Strip, I realized I was the only person crossing the border checkpoint that day. But I immediately saw that streets were vibrant with people shopping and wending through heavy traffic. There are hardly any working traffic lights in Gaza City, so drivers wave their hands out their windows to alert others to let them pass.

Despite the liveliness, recent trauma lingered in the air: In May, Israeli airstrikes destroyed several buildings and at least 264 Palestinians died. The fighting came after thousands of rockets were fired from Gaza into Israel, where at least 16 people died. Workers were still cleaning up when I visited in late August, some of them recycling rubble — such as metal from foundations — to use for rebuilding.

I visited the city of Beit Hanoun, which was heavily damaged. I met Ibrahim, whose apartment was nearly destroyed, and as I looked out from a hole in his living room, I saw children gathered to play a game. Nearby there is a sports complex next to a school. Young people were playing soccer.

Back in Gaza City, families come every night to Union Soldier Park to eat, shop and play. Children and their parents were awaiting their turn to pay for a ride on an electric bike decorated with LED lights. In another part of town, not too far away, the bazaar and the markets were filled ahead of the weekend.

The beach in Gaza City is the most popular destination for locals, particularly because the Israeli government, which occupies the territory, generally does not allow them to leave Gaza. Families picnicked in the late afternoon and then stayed to watch their kids swim until after sunset. One of the local traditions when someone gets married is to parade down the middle of a beachfront road so the groom can dance with relatives and friends.

Amid the activities, I noticed that many people were not wearing face coverings, and I learned that the coronavirus vaccination rate is low. The health department started placing posters around the city to urge vaccination and set up a weekly lottery to award money to those who get immunized.

I also attended the funeral of a boy named Omar Abu al-Nil, who was wounded by the Israeli army — probably by a bullet — during one of the frequent protests at the border. He later died at the hospital from his wounds. More than 100 people attended, mainly men. They carried Omar to the cemetery and buried him as his father watched.

Salwan Georges is a Washington Post staff photographer.

Beyond the Numbers

At home, i constructed a photo diary to show the pandemic’s human toll, text and photographs by beth galton.

I n March 2020, while the coronavirus began its universal spread, my world in New York City became my apartment. I knew that to keep safe I wouldn’t be able to access my studio, so I brought my camera home and constructed a small studio next to a window.

I began my days looking at the New York Times and The Washington Post online, hoping to find a glimmer of positive news. What I found and became obsessed with were the maps, charts and headlines, all of which were tracking the coronavirus’s spread. I printed them out to see how the disease had multiplied and moved, soon realizing that each of these little visual changes affected millions of people. With time, photographs of people who had died began to appear in the news. Grids of faces filled the screen; many died alone, without family or friends beside them.

This series reflects my emotions and thoughts through the past year and a half. By photographing data and images, combined with botanicals, my intent was to speak to the humanity of those affected by this pandemic. I used motion in the images to help convey the chaos and apprehensions we were all experiencing. I now see that this assemblage is a visual diary of my life during the pandemic.

Beth Galton is a photographer in New York.

Finding Hope in Seclusion

A self-described sickle cell warrior must stay home to keep safe, text and photographs by endia beal.

O nyekachukwu Onochie, who goes by Onyeka, is a 28-year-old African American woman born with sickle cell anemia. She describes herself as a sickle cell warrior who lives each day like it’s her last. “When I was younger,” she told me, “I thought I would live until my mid-20s because I knew other people with sickle cell that died in their 20s.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes sickle cell anemia as an inherited red blood cell disorder that causes those cells to become hard and sticky, and appear C-shaped. Healthy red blood cells are round and move through small blood vessels to carry oxygen, whereas sickle cells die earlier and transport less oxygen. The disorder can cause debilitating pain and organ failure.

In June 2020, Onyeka began preparing her body for a stem cell transplant — a new treatment — and underwent the procedure in April. She is now home in Winston-Salem, N.C., recovering from the transplant. Despite the positive results thus far, Onyeka’s immune system is compromised and she is at greater risk of severe illness or death from viruses.

I asked about her life during the pandemic. She told me: “My new normal includes video chat lunch dates. I have more energy now than ever before, but I have to stay indoors to protect myself from airborne viruses, among other things.” Onyeka believes she has been given a new life with endless possibilities — even though she is temporarily homebound.

Endia Beal is an artist based in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Baker’s Choice

A fun-loving, self-taught baker decides to open her shop despite the pandemic, text and photographs by marvin joseph.

T iffany Lightfoot is the owner and founder of My Cake Theory, where she merges her love of fashion with her gifts as a baker. Undaunted by the pandemic, she opened her first brick-and-mortar shop on Capitol Hill last year. Lightfoot, 41, combined the skills she learned as a student at the Fashion Institute of Technology with dozens of hours watching the Food Network and YouTube videos — and spun her self-taught baking into a business. With these photographs I wanted to show how much fun she has baking — while building a career she clearly loves.

Marvin Joseph is a Washington Post staff photographer.

Leap of Faith

Despite low vaccination rates, sicilians resume religious parades, text and photographs by michael robinson chavez.

T he island of Sicily has been overrun and conquered by numerous empires and civilizations. The year 2020 brought a new and deadly conqueror, the coronavirus. The lockdown was absolute — even church doors were shut tight. But in 2021, Sicilians brought life and traditions back to their streets.

Saint’s days, or festas, are important events on the Sicilian calendar. Last year, for the first time in more than a century, some towns canceled their festas. The arrival of vaccines this year seemed to offer hope that the processions would once again march down the ancient streets. However, a surge in summer tourism, while helping the local economy, also boosted the coronavirus infection rate.

Sicily has the lowest vaccination rate in Italy. Nevertheless, scaled-down celebrations have reappeared in the island’s streets. In the capital city of Palermo, residents gathered for the festa honoring the Maria della Mercede (Madonna of Mercy), which dates to the 16th century. Children were hoisted aloft to be blessed by the Virgin as a marching band played in a small piazza fronting the church that bears her name. Local bishops did not permit the normal procession because of the pandemic, so local children had their own, carrying a cardboard re-creation of the Virgin through the labyrinth of the famous Il Capo district’s narrow streets.

As the fireworks blossomed overhead and the marching band played on, it was easy to see that Sicilians were embracing a centuries-old tradition that seems certain to last for many more to come.

Michael Robinson Chavez is a Washington Post staff photographer.

Defiant Glamour

After long months of covid confinement, a fearless return to 2019 in miami beach, text and photographs by lucía vázquez.

O n Miami Beach’s Ocean Drive I’ve seen drunk girls hitting other drunk girls, and I’ve seen men high on whatever they could afford, zombie-walking with their mouths and eyes wide open amid the tourists. I’ve seen partyers sprawled on the pavement just a few feet from the Villa Casa Casuarina, the former Versace mansion.

I’ve seen groups of women wearing fake eyelashes as long and thick as a broom, and flashing miniature bras, and smoking marijuana by a palm tree in the park, next to families going to the beach. I’ve seen five girls standing on the back of a white open-air Jeep twerking in their underwear toward the street.

My photographs, taken in August, capture South Beach immersed in this untamed party mood with the menace of the delta variant as backdrop. They document young women enjoying the summer after more than a year of confinement. Traveling from around the country, they made the most of their return to social life by showing off their style and skin, wearing their boldest party attire. I was drawn to the fearlessness of their outfits and their confidence; I wanted to show how these women identify themselves and wish to be perceived, a year and a half after covid-19 changed the world.

Lucía Vázquez is a journalist and photographer based in New York and Buenos Aires.

A Giving Spirit

‘this pandemic has taught me to be even closer to my family and friends’, text and photographs by octavio jones.

M arlise Tolbert-Jones, who works part time for an air conditioning company in Tampa, spends most of her time caring for her 91-year-old father, Rudolph Tolbert, and her aunt Frances Pascoe, who is 89. Marlise visits them daily to make sure they’re eating a good breakfast and taking their medications. In addition to being a caregiver, Marlise, 57, volunteers for a local nonprofit food pantry, where she helps distribute groceries for families. Also, she volunteers at her church’s food pantry, where food is distributed every Saturday morning.

“I’m doing this because of my [late] mother, who would want me to be there for the family and the community,” she told me. “I’ve had my struggles. I’ve been down before, but God has just kept me stable and given me the strength to keep going. This pandemic has taught me to be even closer to my family and friends.”

Octavio Jones is an independent photojournalist based in Tampa.

First, people paused. Then they took stock. Then they persevered.

Text and photographs by anastassia whitty.

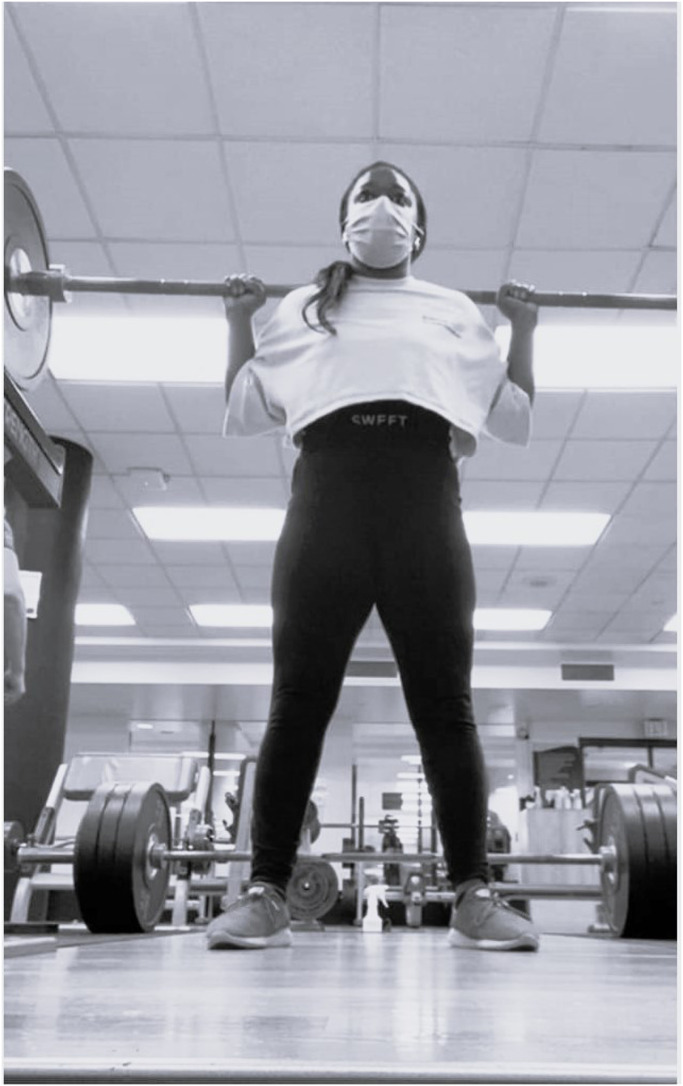

W e all know the pandemic has challenged people and altered daily routines. I created this photo essay to highlight the perspectives and experiences of everyday people, specifically African Americans: What does their “new normal” look like? I also wanted to demonstrate how they were able to persevere. One such person is Maria J. Hackett, 30, a Brooklyn photographer, dancer and mother of a daughter, NiNi. Both are featured on the cover.

I asked Maria her thoughts on what the pandemic has meant for her. “Quarantine opened up an opportunity to live in a way that was more healthy while taking on much-needed deep healing,” she told me. “It was my mental and emotional health that began breaking me down physically. ... I put things to a stop as my health began to deteriorate. I decided I will no longer chase money — but stay true to my art, plan and trust that things will come together in a healthier way for us. I focused more on letting my daughter guide us and on her remaining happy with her activities and social life.”

“Enrolling her in camps and classes like dance and gymnastics led me to develop a schedule and routine,” Maria explained, “opening room for me to complete my first dance residency in my return to exploration of movement. I made time to share what I know with her and what she knows with me.”

Jasmine Hamilton of Long Island, 32, talked in similiar terms. She too became more focused on mental health and fitness. She told me: “The pandemic has demonstrated that life is short and valuable, so I’m more open to creating new experiences.”

Anastassia Whitty is a photographer based in New York.

About this story

Photo editing by Dudley M. Brooks and Chloe Coleman. Design and development by Audrey Valbuena. Design editing by Suzette Moyer and Christian Font. Editing by Rich Leiby. Copy editing by Jennifer Abella and Angie Wu.

- Signs of the Times: Public Displays at the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic

From politics and the pandemic to Halloween and graduation, 2020 was notable for its proliferation of citizen signage. This photo essay provides a time capsule of the COVID-19 era in West Philadelphia.

By Kelly Diaz

Like so many people did during those days of fear and uncertainty that marked the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, I brought home a puppy. A “cavachon” (Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and Bichon Frise mix), Matilda (“Tillie”) was eight weeks old when I got her in May 2020, and while she was potty training, she needed up to 10 walks a day.

It was frustrating for me to spend so much time of the day away from my computer, taking breaks that the diligent graduate student in me did not think I had earned.

But I took comfort in Tanya Behrisch’s “Slow” philosophy . In reference to the time she spent cooking for herself and loved ones, she explains:

“Rather than viewing those hours in neoliberal time as ‘lost hours’ I want to shift to a Slow appreciation of ‘gained hours.’ [...] Care work requires Slowing down, taking time to notice what should be done, for whom, when, and how. The Slow movement invites me to explore this relational process through research, writing, and embodied practice of cooking for others (p. 3).”

With this in mind, I realized my puppy would never be so young and impressionable again. Each day she got older, bigger, and more independent. Work would always be there needing my attention, but my precious fur baby would not.

Throughout some of the hardest and most stressful months of my life, I was cheered up by the fresh air, Tillie’s adorable sidewalk strut, and the messages my neighbors displayed in the windows, balconies, porches, and yards of residential buildings and storefronts. I began to consider the visual messaging on graffiti, memorial displays, flyers, and other citizen signage.

Between May and December of 2020, I took photographs of these displays on my iPhone as I walked Tillie through the streets of West Philadelphia, in particular the University City and Spruce Hill neighborhoods. You will find a gallery of these images below.

A Constellation of Issues

In a Slate.com article about the trend of posting signs in the early months of the pandemic, journalist Henry Grabar wrote, “Chicago is empty of people but full of signs [...] Every city is like this now, as if our protective masks stifled the ability to speak and left us to communicate only in writing.”

As those who lived through 2020 recall, there was no shortage of fodder for signage.

The pandemic coincided with a presidential election, which exponentially increased the degree to which people were displaying a national identity and concern.

Another significant percentage of the signs expressed “thank you” messages for essential workers who were continuing to leave their homes and risk COVID exposure to keep the community running. These were, at times, bright and uplifting artwork to demonstrate one’s positive outlook in the midst of crisis and tragedy.

As protests against racial injustice and anti-Blackness in the United States grew, many residents in my neighborhood displayed either homemade or commercially manufactured Black Lives Matter signs to demonstrate an intolerance for violence and discrimination against Black Americans.

Performing One’s Values

Signs are both display and performance, a way that people articulate their definition of self as someone who takes public health seriously and is community-oriented.

Just as many of the themes overlapped, so too did the media. Images that were made by hand with markers or crayons and hung in windows may have also been photographed and uploaded to Instagram or Facebook. Similarly, the immediate intended audience might be passersby, but it could also be one’s own social media followers or the extended networks of anyone who walks by and takes a picture as I did, and now share with you in the gallery below.

As I took these photos, I thought about Erving Goffman’s 1959 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life . It helped me to see the signs as a means of performing identity, gratitude, care, and allyship. This is not to say that the displays are not genuine, but rather that they are calculated and intentional attempts to put forward into the world an image of oneself through a visual. Goffman writes:

“The individual may attempt to induce the audience to judge him and the situation in a particular way, and he may seek this judgment as an ultimate end in itself, and yet he may not completely believe that he deserves the valuation of self which he asks for or that the impression or reality which he fosters is valid (p. 21).”

Indeed, I saw many signs that seem to have been made and displayed in order to have an audience “judge” (in a positive sense) the person or household sharing that message or “performance.” I imagine that some of my neighbors hoped to be viewed by passersby as anti-racists or feminists or Biden/Harris supporters.

As Goffman suggests, however, many might have found that even after creating the display of care or identity they still felt guilty or insecure about their place in our deeply flawed society. This was certainly true of myself.

What Goes Unseen

Performative allyship has been critiqued widely as a phenomenon wherein people seek attention for their support for justice without doing actual justice work. While I recognize this problem, I can also see merits to the displays of allyship in this context. After all, performing allyship is not in itself a problem, if accompanied by action.

As a new member of the community, it was comforting and affirming to see my neighbors’ values on display through this signage. While I recognized the many problematic ways that people have engaged in virtue signaling, in this case, I wanted my neighbors to signal their virtues to me. If I wanted to know, for example, that it was safe to wear my Pride shirt around the neighborhood, I could find my answer in many of the signs displayed by my neighbors.

I thought about the labor and care people took to make homemade signs, though this does not necessarily point to further social action. I also thought about how it would be easy to judge someone for simply displaying a commercially made sign, though at times those signs come as a result of a donation to a justice organization. In this case, people displaying them have “put their money where their mouth is” and directly supported the cause.

Assigning motivation was, of course, impossible. In these times of social distancing, I was unable to pair the displays of allyship through signage with discussions with the creators about their social justice work. It was also not clear which signs came from allies and which came from people directly impacted.

Politics on Display

While lawn and window signs are common every election season, I do wonder if there was an increase in signage to compensate for the loss of other forms of political identity and candidate support during physical distancing. For example, people who usually wear campaign t-shirts, pins, and hats might have instead opted for a sign that they could display from the safety of their home, while still reaching an audience.

The signs were also a reflection of our local political leanings. The prevalence of Black Lives Matter, Biden/Harris signs, and COVID-19 safety signs was notable in the absence of signage in support of police, the Trump/Pence administration, or claims that COVID-19 was a hoax to be ignored.

The few times I left the community this summer I found myself in areas with large numbers of Blue Lives Matter products, signs demanding that the government reopen restaurants and shops, and Trump 2020 flags.

The difference in my degree of safety and comfort as a queer woman of color was palpable in those communities versus in my own, and I was proud to see the intolerance of racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination on display amongst West Philadelphia residents — acknowledging, of course, that these generalizations do not apply to all residents.

Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times

Another thing that caught my attention were the contrasts in subject matter. While people were mourning the loss of lives and experiences due to COVID-19 and white supremacy, people were also celebrating graduations and holidays. Once mundane Halloween decorations such as tombstones and skeletons took on a new meaning for me when I encountered them during a period of mass death.

While people were calling for police abolition, they were also expressing gratitude for postal and sanitation workers who had been working through frustrating budget cuts and high COVID-19 risk.

The images also demonstrated the ways in which mundane and regular tasks persisted even throughout the COVID crisis. People continued to grab coffee at the local café, get their flu shots, and wash their clothes at the laundromat, even as the logistics of these tasks changed greatly.

Although many photographs below captured similar displays, no two photos are identical. Even when signs were exactly the same in content, they varied in terms of placement, materiality, size, and many other factors.

This collection is useful even in 2020 as a way to understand West Philadelphia residents in 2020, and it will likely be even more valuable in future years as a time capsule. While I took these photos without asking for permission, I hope that by sharing them, I am honoring the West Philadelphia community that gave me a warm welcome and offered me a home during some of the most difficult months of my life.

Kelly Diaz is a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication.

West Philadelphia During COVID

Use the arrows to scroll through photos taken by Kelly Diaz on her iPhone between May and December of 2020.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Dark Persistence: Black College Women's COVID-19 Photo Essays

Jennifer d turner.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Jennifer D. Turner, Associate Professor in Reading Education, Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership, University of Maryland, 2233 Benjamin Building, College Park, MD 20742, USA. Email: [email protected]

Received 2022 Apr 5; Revised 2023 Jun 15; Accepted 2022 Dec 4; Issue date 2023 Jun.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until permissions are revoked in writing. Upon expiration of these permissions, PMC is granted a perpetual license to make this article available via PMC and Europe PMC, consistent with existing copyright protections.

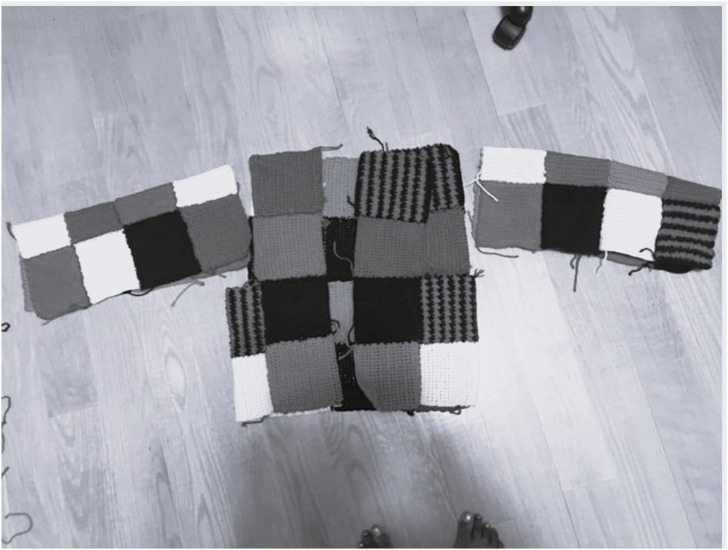

Guided by intersectional multimodal literacy frameworks and analytic methods, this qualitative study explored how seven high-achieving Black undergraduate women's photo essays visually and textually represented their persistence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo essays, in this context, are intersectional multimodal compositions that use images and words to articulate the challenges that the women faced during COVID-19 and the resources that promoted their persistence. Data sources included a demographic questionnaire, the women's digital photo essays, and lengthy photo-elicitation interviews with the women on Zoom. Findings reveal that the women's photo essays evoked an endarkened persistence, rooted in the legacy of Black people's collective struggle and survival, and represented by two interrelated themes: Affirming Black Beauty (i.e., Embracing natural Black hair and Caring for Black female bodies) and Honoring the Spirit (i.e., (Re)connecting with sistafriends, (Re)claiming rest, and Nurturing creativity). Research and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: multimodal/media literacies, feminist studies/research, higher education, gender, race and ethnicity

My photos show how I’ve been able to find motivation at this institution where I’m not the same as everyone else. I have persisted during COVID-19 by continuing to find things that bring me joy despite the fact that there's a lot of fear … I’ve struggled, but I’m still here and there is hope.

Imani's (all names are pseudonyms) words and images in her photo essay break the silence surrounding high-achieving, Black undergraduate women at predominantly white universities (PWUs) and their COVID-19 experiences. The traumas that Black college women, and Black women more generally, have experienced since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020 are oftentimes ignored by U.S. society ( Pennant, 2022 ). It is well-known that COVID-19 disproportionately affects Black and Latinx communities ( Jones et al., 2022 ), yet many are unaware that Black women are three times more likely than white and Asian men to die from the disease ( Njoku & Evans, 2022 ). Black women are also more likely to experience consequential impacts of COVID-19, including deteriorating physical and mental healthand economic instability ( Chandler et al., 2021 ). At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the traumas that Black women have endured from structural racism in the United States. As Black women grieved for George Floyd, William Howard Green, and other unarmed Black men murdered by police in 2020, they were equally devastated by the state-sanctioned murders of Breonna Taylor and countless other unarmed Black women whose names were erased by the media ( Pennant, 2022 )—heartbreaking reminders that Black women's bodies, literacies, and lives are disposable. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Black undergraduate women like Imani navigate physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual challenges, and many suffer—and persist—in silence.

As a Black college woman, Imani recognizes that her persistence in the global pandemic reflects that she is “not the same as everyone else.” Her words underscore how high-achieving Black undergraduate women are socially located at the intersections of race, gender, and academic status, and due to their membership in two marginalized groups (i.e., women and Black people), they experience raced-gendered oppressions on higher education campuses and in society ( Davis, 2018 ; Patton & Croom, 2017 ). At PWUs, these oppressive forces work to diminish Black college women's high-grade point averages (GPAs), graduation rates, honors program participation, and other scholastic achievements ( Davis, 2018 ; Patton & Croom, 2017 ). High-achieving Black undergraduate women are particularly marginalized by broader diversity discourses that aggregate student experiences with a singular focus on race (e.g., African American) or gender (e.g., women of color), erasing their distinctive voices from policies, programs, and pedagogies at PWUs ( Davis, 2018 ). This erasure has been exacerbated in the COVID-19 era, as pandemic impact research frequently aggregates Black college women's and men's experiences ( Jones et al., 2022 ). To my knowledge, there are no studies focused specifically on Black women who have been academically successful despite the COVID-19 pandemic, and this lack of intersectional research marginalizes the voices and experiences of women like Imani.

Imani's assertion that she is “not the same as everyone else” also implores literacy scholars to push beyond the boundaries of print-centric research toward critical multimodal paradigms that center the rich compositional practices and products of young people of color. When asked about her experiences creating the photo essay, Imani noted, “This was a super fun project for me. I’m a photographer, and I love photos and making collages where I can express myself and document my experiences.” Here, Imani foregrounds how she composes with images and words to express herself—who she is as a Black, high-achieving college woman—and her intersectional experiences during COVID-19. Historically and contemporarily, Black women have engaged literacies across multiple modalities to define their raced-gendered identities and assert their humanity ( Muhammad & Womack, 2015 ; Price-Dennis et al., 2017 ). Despite their rich multiliterate legacies, high-achieving Black college women like Imani are frequently (mis)perceived as unintelligent, incapable, and illiterate compared to their white peers at PWUs ( Kynard, 2010 ). In college English classrooms, Black undergraduate women may not demonstrate their full multimodal compositional repertoires because conventional pedagogies overemphasize standardization and skills, which “shifts writing from being a source of possibility to one of ridicule and limitation” ( Smith et al., 2022 , p. 1674). In addition, high-achieving Black college women and their multimodal literacies have been marginalized in the research literature “due to the reductive nature of how literacies in college settings are imagined, [and] the lack of attention paid to out-of-school literacies” ( Kynard, 2010 , p. 35).

Imani's words suggest that scholarship that centers on high-achieving Black college women and elevates their multimodal compositions is essential for promoting their educational, socioemotional, and mental well-being beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Toward that end, this article highlights how seven high-achieving Black college women's photo essays represented persistence and illuminated, in Imani's words, “the things that brought joy” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, “photo essay” represents a type of intersectional multimodal composition that Black college women author to “affirm the self and critique dominant narratives of whiteness” ( Smith et al., 2022 , p. 1676). Guided by intersectional multimodal literacy frameworks and analytic methods, I explore the following question:

How do Black undergraduate women's photo essays visually and textually represent their persistence during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Critical Framings: The Intersectionality of Black College Women's Multimodal Literacies

This study brings together intersectional literacy theories ( Green et al., 2021 ), New Literacy perspectives ( New London Group, 1996 ), and endarkened feminist epistemology frameworks ( Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ) to articulate the intersectionality of Black college women's multimodal literacies. Intersectional literacy theories are rooted in the concept of intersectionality , defined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (2017) as a “lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects.” Frequently misrepresented as a theory of multiple identities, intersectionality is a critical framework for articulating and examining how simultaneous group memberships significantly shape people's experiences of power and privilege ( Collins, 2009 ; Crenshaw, 2017 ). More specifically, intersectionality illuminates the complex, cumulative effects of multiple oppressions that women of color experience at the intersections of race and gender within a white supremacist patriarchal society ( Evans-Winters & Esposito, 2010 ). For example, Black women face multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination in mainstream institutions (e.g., racism and sexism); therefore, their lived experiences are different from those of white women and men of color ( Crenshaw, 2017 ; Evans-Winters & Esposito, 2010 ).

Informed by these perspectives, I offer an intersectional multimodal literacy framework to articulate how Black college women's multimodal communicative practices are situated in and expressive of their raced-gendered ways of knowing, doing, and being. Adapting Green et al.'s ( 2021 ) framework for intersectionalizing racial literacies, I understand Black college women's intersectional multimodal literacies as endarkened , engendered , and embodied . The terms “endarkened” and “engendered” move away from white feminisms and their “enlightened” ideologies and instead articulate Black women's realities located in Black feminist thought ( Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ). This shift illuminates the unique cultural standpoints that Black women occupy based on their shared legacy of struggle within interlocking and intermeshing systems of oppression in U.S. society ( Collins, 2009 ; Crenshaw, 2017 ). Drawing on the specialized knowledge acquired from their endarkened and engendered standpoints, Black women move beyond victim status, using their agency and empowerment to (re)define Black womanhood; love themselves, their families, and their communities; promote wellness for themselves and others; and persist in fighting against societal oppressions ( Collins, 2009 ; Dillard, 2000 ; hooks, 1993 ). As such, Black women engage intersectional multimodal literacies as alternate sites of knowledge production and textual practice that materialize “the self-expression, self-definition, and validation of Black female understanding” ( Dillard, 2000 , p. 664).

Black college women's intersectional multimodal literacies are also embodied and therefore represent and reflect their “full Black womanness” ( Green et al., 2021 ). In contrast to Westernized dichotomies between the material (i.e., the body) and the nonmaterial (i.e., the spiritual), Black women hold African worldviews that are holistic, in which body and spirit coalesce and are (re)affirmed in divine relationship to self, community, and Creator ( Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ). By leveraging their intersectional multimodal literacies, Black women compose intellectual and creative multimodal works (e.g., music, literature, art, and photography) that facilitate the (re)membering of their mental, emotional, and spiritual selves, allowing them to repair the fragmentation caused by a white supremacist patriarchal society ( Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ). Moreover, intersectional multimodal literacies serve as restorative practices that allow Black women to represent and reaffirm the people, places, and spaces that promote their humanity and healing, including psychological counseling or therapy and self-care practices, friendships with Black women and women of color, places of rest (e.g., gardens), religious communities (e.g., churches), and political advocacy groups ( Adkins-Jackson et al., 2022 ; Collins, 2009 ; Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ). Consequently, Black women's intersectional multimodal literacies, and the creative textual works that they inspire and animate, perform the historical and contemporary functions of literacies that protect and serve ( Richardson, 2002 ) the intellectuality, psychosocial wellness, and persistence of Black women.

Though small, the extant literature demonstrates that Black college women practice a variety of modes of literate meaning-making situated at the intersections of race and gender. The Black college women in Ohito's (2020) study created multimodal compositions that illustrated the heterogeneity, resilience, and humanity of Black people across time and place. Moreover, Kynard (2010) revealed the power of digital multimodal writing in a Sista-cypher with 13 Black undergraduate women at an urban PWU. In the safety of their virtual hush harbor, the Sistas’ multimodal choices (e.g., font size) and rhetorical moves animated their counterstorytelling and interrogation of structural racism at their PWU and in society. Collectively, this research illuminates how Black college women at PWUs create multimodal compositions “to cope with and, in many cases, transcend the confines of intersecting oppressions” ( Collins, 2009 , p. 98).

Young Black Women's Photo Essays as Intersectional Multimodal Composition

As photographic writers, young Black women compose intersectional multimodal compositions that “affirm themselves, the(ir) world, and the multidimensionality of young Black womanhood” ( Price-Dennis et al., 2017 , p. 5). Historically, Black women have engaged in writing to achieve four central purposes: (a) expressing self-defined intersectional identities, (b) promoting persistence in the face of societal oppression, (c) building capacity for liberatory work, and (d) advancing collective transformation and social justice ( Muhammad & Behizadeh, 2015 ). Contemporary young Black women in their adolescent and early adult years, rooted in the rich authorial legacies of their Black foremothers, compose photo essays and other rich multimodal compositions that nurture their liberation, healing, and persistence in an anti-Black, patriarchal society (e.g., Muhammad & Womack, 2015 ; Ohito, 2020 ; Price-Dennis et al., 2017 ; Turner & Griffin, 2020 ; Wissman, 2008 ). In this study, photo essays are intersectional multimodal compositions where young Black women represent their full Black womanness, entangled and imbued with endarkened, engendered, and embodied meanings, through a combination of visual modes (i.e., photographic imagery) and linguistic modes (e.g., written captions), and may include other communicative modes like aurality, gesture, and spatiality ( New London Group, 1996 ). Moreover, photo essays highlight and reflect how Black women engage their creative energies, which are ancestral life forces for Black girls and women ( Brown, 2013 ; Dillard, 2000 ), in “ongoing acts of self-preservation and resistance” ( Green et al., 2021 , p. 143).

An emerging body of research has theorized how young Black women mobilize visual (e.g., photographic images), textual (e.g., written captions), and their epistemological resources (e.g., intersectional knowledges) “to negotiate public perceptions and author their own lives rather than being defined by others” ( Muhammad & Womack, 2015 , p. 8). Some young Black women compose photographic writing about thier religious affiliations to refuse the fragmented views of Black womanhood propagated in society and to (re)member their full Black womanness and the interconnectedness of their minds, bodies, and spirits. Candace, a 16-year-old African American girl, illustrated salient intellectual, emotional, and spiritual aspects of herself through photographs of her praise dancing with a group of Black women at church and a self-portrait in a classic thinker's pose ( Manning et al., 2015 ). Reflecting on her photographs and writings, Candace validated her self-worth as a young Christian Black woman by “justify[ing] who I am through myself and God and not by what others believe” ( Manning et al., 2015 , p. 148). In Griffin and Turner's (2023) research, Arielle Mack, a Black woman student-athlete at a PWU, foregrounded her full Black womanness in her photo essay, highlighting how her multiple intersectional identities (e.g., daughter, sister, activist, Christian, and future physical therapist) animated her academic and athletic life. In so doing, Arielle rejected her university's vision of her body as a “tool” that labors to enrich white postsecondary institutions.

Other studies demonstrate how photographic writing opens space for young Black women to understand their full Black womanness as a reflection of the divine in their relationship with themselves, their families, their friends, their communities, and their ancestors ( Dillard, 2000 , 2016 ). For example, representations of beauty and wellness are particularly relevant to young Black women because the popular media often depicts Black female bodies as physically unattractive, unhealthy, and nonfeminine compared to White women ( Muhammad & Womack, 2015 ; Price-Dennis et al., 2017 ). In Hampton and Desjourdy's (2013) study, Kanisha, a Black Canadian adolescent girl, challenged media depictions of white women as the ideal beauty through a photographic series titled Road to Salvation . Through reflective writings and images of her natural face and Black hair-care practices, Kanisha represented the sacredness and authenticity of beauty in her culture. Kanisha's photographs, taken on her bed, also depicted the ways that resting nourished her body, mind, and spirit and provided space for healing the broken parts of herself ( hooks, 1993 ). Along similar lines, Jordan, a Black adolescent girl in Muhammad and Womack's (2015) study contested Eurocentric standards of beauty and documented her own journey toward self-love. By pinning photographs and brief commentaries on her Pinterest board, Jordan illuminated the false binaries of “good” (white) hair (e.g., long, straight, and silky) and “bad” (Black) hair (e.g., short and curly), processed her own feelings about her hair, and began reimagining “what beauty could and should look like” ( Muhammad & Womack, 2015 , p. 24).

Relatedly, young Black women compose photo essays to celebrate the fullness of their Black womanness and the wholeness of their relationships, rejecting public stereotypes that they are too loud, violent, and aggressive to sustain close friendships ( Brown, 2013 ; Price-Dennis et al., 2017 ). In Wissman's ( 2008 ) research, African American adolescent girls created photographic self-portraits to highlight the literacies (e.g., writing), cultural practices (e.g., braided hairstyles), and loving relationships (e.g., daughter, sister, and friend) that were significant in their lives, but that their school overlooked, misjudged, or dismissed. Similarly, young Black girls in Brown’s (2013) study took photographs of themselves talking, playing, laughing, and dancing with other Black girls and Black women to illuminate the close friendships, love, caring, and hope cultivated in their intergenerational group of “homegirls.” Taken together, these studies suggest that young Black girls engage in truth-telling through photographic writing that exposes “the inaccurate ways in which they … were being characterized and consistently asserts their own power to name, represent, and define their own identities and realities” ( Wissman, 2008 , p. 35). My study takes inspiration from this work and focuses on Black college women's photo essays about their persistence throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

Study Design and Researcher Positionality