MRC / UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit

The Medical Research Council (MRC)/UVRI and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Uganda Research Unit conducts research on HIV disease and related infections to facilitate their control in Uganda and elsewhere in Africa. Specifically it investigates the determinants of HIV infection and subsequent disease progression in the African context; to identify and evaluate new strategies aiming at the prevention of HIV infection as well as interventions aiming to alleviate the clinical and social consequences of the infection. The work is multidisciplinary, reflecting the wide ranging nature of the problems caused by HIV. Activities range from virology, and immunology to clinical studies and intervention trials, epidemiological studies, behavioural research and health economy studies, supported by strong statistical and laboratory services and a community development programme.

Find out more about the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit .

Last updated: 31 March 2022

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

Data Sharing

- transparent and easily scrutinised, helping to increase public trust

- easy to re-use and build upon

- collaborative and efficient

Why share our data

Making MRC/UVRI & LSHTM data easily accessible enables other researchers to reuse and analyze the data from other perspectives, with the potential of offering new insights from the original work. Making data available from previous experiments or observations is essential to new discoveries, openness helps to accelerate the pace of science.

Data sharing charge/Open access

All Medical Research Council (MRC) funded researchers are expected to comply with the UKRI open access policy .

In line with MRC, MUL strongly promotes the principles of open research data and aims to make the research process and findings as open, understandable and reproducible as possible. Sharing data will enhance the use of existing data, avoid duplication of research effort and stimulate new discoveries. To ease the sharing data a small charge is levied to cover activities involved required to prepare data for sharing this includes

- Staff time for data processing (anonymisation, cleaning, preparing data for sharing, etc.)

- Software-related training

- Technical services such as cloud storage, server maintenance, domain hosting charges, etc.

The Data Sharing Committee (DSC)

All study data collected by the Unit are of sufficient scale or uniqueness to be of potential value to the wider research community and our aim is to maximize the use of our research data for the benefit of the public, to facilitate this an independent Data sharing committee was created.

This is the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research unit (Unit’s) Committee that is responsible for evaluating requests for the Unit’s data and lab samples by external researchers. The committee works in consultation with the Principal investigators, Unit Director and Research Governance.

Data Sharing: Processes

Potential Requesters are strongly encouraged to approach the relevant study investigators informally to discuss feasibility of data sharing. Study investigators/requestors can refer such requests using the data sharing agreement to the Data Sharing Coordinator on [email protected] who will share the requests with the independent data sharing committee. A feedback shall be given in four weeks.

How to request for data

To request for data, access the Data sharing policy and fill the relevant data sharing agreement for completed studies or ongoing studies/collaboration and send the request to the Data Sharing Coordinator on [email protected] .

Data that is readily available for sharing at the Unit includes the different rounds for:

- General Population Cohort (GPC)

- EMABS COHORT

- ENTEBBE COHORT

Uganda Virus Research Institute

Republic of uganda, search form.

- Core Competencies

- Bio-Safety Committee

- Contracts Committee

- Evaluation Committee

- Finance Committee

- Housing Committee

- Research & Ethics Committee

- UVRI Training Committee

- General Virology

- Arbovirology

- Epidemiology

- Finance and Administration

- News Updates

- COVID-19 Phylodynamics Dashboard

- EDCTP-EACCR2

- Target Malaria

- UVRI Clinic

- Mentorship and Grant writing training

- Research Management Training

- UVRI Internship Forms

- Publications

You are here

Mrc unit in uganda gets new director.

Prof Nyirenda is currently Deputy Director at the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit , Professor of Medicine and Global Non-Communicable Diseases, and Head of the Unit’s Non-Communicable Disease Research theme.

His prominent career has ranged from molecular medicine to clinical and public health research, including investigations into non-communicable diseases, particularly around diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. He also has a strong interest in capacity building across Africa.

Prof Nyirenda holds a PhD in Molecular Medicine from the University of Edinburgh and is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He worked at the University of Edinburgh with the support of the MRC Clinician Scientists Fellowship award, and returned to his home country as Associate Director of Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Research Programme and subsequently Director of the Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit before joining the MRC/UVRI &LSHTM Uganda Research Unit in 2016.

Upon accepting the offer, he said: “I am deeply honoured and excited to take on the role of Director of this exceptional Unit at this pivotal moment. I look forward to contributing to its further growth, creating new opportunities, strengthening our research themes in strategic areas, forging intentional collaborations and partnerships, and maximising the capacity to translate our research. The stars are aligned for our collective success as a hub for excellence in research and training in the region."

LSHTM Director, Liam Smeeth, welcomed the announcement: “We had a very strong field of applicants for the role, but Prof Nyirenda impressed us with his vision for the Unit, his calm authority, and obvious quality as a scientific leader. I very much look forward to working in partnership with him to build on the success of the Unit. An opportunity for me to express huge thanks and appreciation to Prof Kaleebu for his amazing work heading the Unit for the past 13 years. During this time the Unit has made many important contributions, not least to the COVID-19 pandemic in the East African region.”

MRC Executive Chair Prof Patrick Chinnery, said: "I am delighted that Professor Moffat Nyirenda will be the new Director of MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit. Prof Nyirenda is an outstanding researcher in endocrinology and metabolic disease with a deep understanding of the Unit and its potential from his current role as Deputy Director. I am excited about his forward-looking vision which will further strengthen the Unit as an international hub for world-leading science that not only addresses key health challenges faced by communities in Uganda, but also has global relevance by tackling fundamentally important questions.

“In this, he will build on a substantial legacy from the outgoing Director, Professor Pontiano Kaleebu, who has led the Unit effectively for over 13 years and ensured its research translated into real-world policies with real benefits to patients both locally and regionally."

During Prof Kaleebu’s tenure he oversaw many achievements including expanding the Unit’s research expertise beyond HIV into other viral pathogens, vaccine research and non-communicable diseases, and training many young scientists as the next generation of health leaders. He will now be devoting his time to immunovirology research.

The appointment follows an extensive recruitment process from a panel that included public health experts from across African and UK institutes, coordinated by a specialist executive search firm.

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

New director announced for mrc unit in uganda.

Prof Nyirenda is currently Deputy Director at the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit , Professor of Medicine and Global Non-Communicable Diseases, and Head of the Unit’s Non-Communicable Disease Research theme.

His prominent career has ranged from molecular medicine to clinical and public health research, including investigations into non-communicable diseases, particularly around diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. He also has a strong interest in capacity building across Africa.

Prof Nyirenda holds a PhD in Molecular Medicine from the University of Edinburgh and is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He worked at the University of Edinburgh with the support of the MRC Clinician Scientists Fellowship award, and returned to his home country as Associate Director of Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Research Programme and subsequently Director of the Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit before joining the MRC/UVRI &LSHTM Uganda Research Unit in 2016.

Upon accepting the offer, he said: “I am deeply honoured and excited to take on the role of Director of this exceptional Unit at this pivotal moment. I look forward to contributing to its further growth, creating new opportunities, strengthening our research themes in strategic areas, forging intentional collaborations and partnerships, and maximising the capacity to translate our research. The stars are aligned for our collective success as a hub for excellence in research and training in the region."

LSHTM Director, Liam Smeeth, welcomed the announcement: “We had a very strong field of applicants for the role, but Prof Nyirenda impressed us with his vision for the Unit, his calm authority, and obvious quality as a scientific leader. I very much look forward to working in partnership with him to build on the success of the Unit. An opportunity for me to express huge thanks and appreciation to Prof Kaleebu for his amazing work heading the Unit for the past 13 years. During this time the Unit has made many important contributions, not least to the COVID-19 pandemic in the East African region.”

MRC Executive Chair Prof Patrick Chinnery, said: "I am delighted that Professor Moffat Nyirenda will be the new Director of MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit. Prof Nyirenda is an outstanding researcher in endocrinology and metabolic disease with a deep understanding of the Unit and its potential from his current role as Deputy Director. I am excited about his forward-looking vision which will further strengthen the Unit as an international hub for world-leading science that not only addresses key health challenges faced by communities in Uganda, but also has global relevance by tackling fundamentally important questions.

“In this, he will build on a substantial legacy from the outgoing Director, Professor Pontiano Kaleebu, who has led the Unit effectively for over 13 years and ensured its research translated into real-world policies with real benefits to patients both locally and regionally."

During Prof Kaleebu’s tenure he oversaw many achievements including expanding the Unit’s research expertise beyond HIV into other viral pathogens, vaccine research and non-communicable diseases, and training many young scientists as the next generation of health leaders. He will now be devoting his time to immunovirology research.

The appointment follows an extensive recruitment process from a panel that included public health experts from across African and UK institutes, coordinated by a specialist executive search firm.

LSHTM's short courses provide opportunities to study specialised topics across a broad range of public and global health fields. From AMR to vaccines, travel medicine to clinical trials, and modelling to malaria, refresh your skills and join one of our short courses today.

Related links

- Study with us

- Research and impact

- News and events

Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and get all the latest research news, views, videos and event listings from the School.

Subscribe to RSS feed

Uganda function fbs_click() { u=location.href;t=document.title; window.open('http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u='+encodeURIComponent(u)+'?t='+encodeURIComponent(t)+'&u=http%3A%2F%2Fhttps%3A%2F%2Fhealthresearchwebafrica.org.za','sharer','toolbar=0,status=0,width=626,height=436');return false;} " onclick="return fbs_click()" target="_blank" style="text-decoration:none;"> function tws_click() {u=location.href;t=document.title;window.open('http://twitter.com/share?url='+encodeURIComponent(u)+'&text=Medical+Research+Council+Programme+on+AIDS+-+Uganda+-+Health+Research+Web+%28HRWeb%29','sharer','toolbar=0,status=0,width=626,height=436');return false;} " onclick="return tws_click()" target="_blank" style="text-decoration:none;">

- Key Institutions / Networks

- Contact Info.

- Organisation Info.

- Publications

- Supplementary Info.

Medical Research Council Programme on AIDS

Telephone number: +256 41 320272/32004

Fax Number: +256 41 321137

Physical address Uganda Virus Research Institute (MRC/UVRI) P.O. Box 49, Entebbe Uganda

Country Uganda

* Regional pages of relevance for your country: Africa

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Medical Research Council (UK)/Uganda Virus Research Institute Uganda Research Unit on AIDS – ‘25 years of research through partnerships’

A m elliott, e katongole-mbidde.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding Author Pontiano Kaleebu , MRC/UVRI Uganda Research Unit on AIDS, c/o Uganda Virus Research Institute Plot 51-57, Nakiwogo Road, P.O Box 49, Entebbe, Uganda. Tel.: +256 414 320809/321461 or +256 417 704 000; E-mail: [email protected]

Issue date 2015 Feb.

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

For the past 25 years, the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute Uganda Research Unit on AIDS has conducted research on HIV-1, coinfections and, more recently, on non-communicable diseases. Working with various partners, the research findings of the Unit have contributed to the understanding and control of the HIV epidemic both in Uganda and globally, and informed the future development of biomedical HIV interventions, health policy and practice. In this report, as we celebrate our silver jubilee, we describe some of these achievements and the Unit's multidisciplinary approach to research. We also discuss the future direction of the Unit; an exemplar of a partnership that has been largely funded from the north but led in the south.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, Uganda, Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute, coinfections, research, multidisciplinary

Introduction

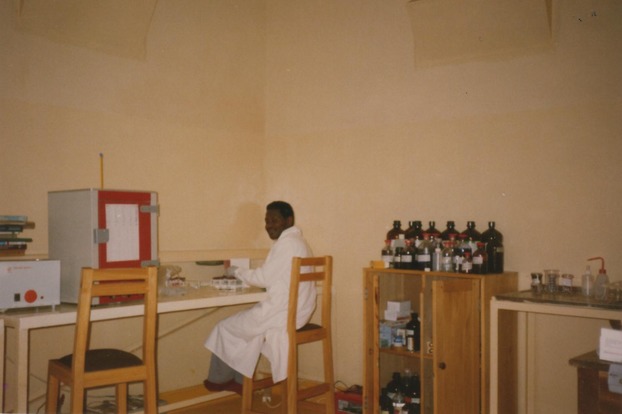

This year 2014, we celebrate 25 years of the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute (MRC/UVRI) Uganda Research Unit on AIDS. On 12th December 1988, the initial memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Uganda and British governments was signed, leading to the establishment of MRC/UVRI. The MRC/UVRI research programme activities were initiated in 1989 in Kyamulibwa, in Masaka district (Figures 1 and 2 ). The unique feature of the programme has been its multidisciplinary nature encompassing epidemiology, clinical medicine, basic science and social science, with strong community development, statistical and laboratory support. Capacity building has also been an important component of the Unit's work. The theme of our celebrations is ‘25 Years of Research Excellence through Partnerships’ in recognition of the fact that the achievements and successes we have registered have only been possible through partnerships.

The laboratory at Kyamulibwa field station in 1990.

Community meeting in Kyamulibwa, Masaka District, 2009.

In 1986, the new Uganda Government recognised the danger of the HIV epidemic and acted quickly to make the problem public, including an appeal for international support to combat the disease. An invitation was extended to the United Kingdom MRC through the Uganda Ministry of Health to support the AIDS Control and Prevention Programme with both human and material resources. MRC sought support to fund the proposed HIV/AIDS research in Uganda and the Overseas Development Administration (ODA) – the predecessor of the UK Department for International Development (DFID) – agreed to fund the research. The MoU establishing the collaboration and the creation of the MRC/ODA/UVRI Programme on AIDS was signed, and the MRC was established at UVRI in Entebbe ( Figure 3 ).

Uganda Virus Research Institute.

At that time, knowledge of the epidemiology of HIV-1 in Africa was based largely on studies of patients attending urban hospitals and of selected urban populations such as antenatal care attendants; there were limited data on the extent of the epidemic among rural populations. Though it was known that HIV is heterosexually transmitted, there were no available data on risk factors for transmission or of rates of disease progression. It was therefore urgent that research be initiated in a rural setting to help fill these knowledge gaps and inform policies on prevention. The research area was selected because of proximity to Rakai district, where the first cases were reported in 1983 and from where the disease was presumed to have spread to neighbouring districts.

The programme grew considerably over the years. New research sites were opened in Masaka, then Entebbe, Kampala and Jinja. Working with various partners, the research findings of the Unit have contributed to the understanding and control of the HIV epidemic in Uganda and globally and informed the future development of biomedical HIV interventions and health policy and practice. We have tackled all aspects of the epidemic from basic science through to public health policy. The achievements have been possible through partnerships established with many different individuals and organisations. We summarise some of these achievements in three periods.

The original research investigated the epidemiology of HIV infection through annual surveys of a General Population Cohort (Nunn et al . [ 55 ]) with associated in-depth qualitative research on the impact of the epidemic in the rural setting (Seeley et al . [ 73 ]). Both a counselling and a community development section were set-up to support research activities and to promote the well-being of community members (Seeley et al . [ 71 ]; Nakibinge et al . [ 49 ]). Activities of this section included the establishment of various programmes such as school health education and community-based health care (Seeley et al . [ 72 ]). The first ten years provided important data on HIV prevalence and incidence including age-specific population attributable risks for HIV-1 infection (Mulder et al . [ 43 ]; Kengeya-Kayondo et al . [ 25 ]). The role of sexual behaviour in the HIV-1 epidemic was confirmed. The factor most strongly associated with increased risk of HIV infection was a greater number of lifetime sexual partners (Malamba et al . [ 32 ]). In addition, early studies showed that young women were at a higher risk of infection than men (Nunn et al . [ 55 ]). On the other hand, HIV infection among children aged 0–12 years was almost exclusively the result of mother-to-child transmission. No infections were attributed to parenteral exposure, non-sexual casual or household contact or insects (Mulder et al . [ 45 ]). Valuable information was generated on the biological and behavioural risk factors influencing transmission (Seeley et al . [ 74 ]) and the impact of the epidemic on children (Kamali et al . [ 21 ]).

Studies showed that the proportions of deaths that would have been avoided in the absence of HIV were 44% for adult men, 50% for adult women and 89% for all adults aged 25–34 years (Mulder et al . [ 43 ]). This work indicated the devastating effects of the epidemic on families and communities in rural areas, where the majority of Ugandans lived. In the mid-1990s, our work showed declining HIV prevalence, especially among young adults in the general population (Mulder et al . [ 44 ]) and later provided the first data on the declining HIV incidence in some age groups (Mbulaiteye et al . [ 34 ]). This may have been because of interventions in the population and suggested that some measures could lead to epidemic control.

In 1990, a clinical cohort of HIV-infected people called the ‘Natural History Cohort’ in the era before antiretroviral treatment (ART) became available was set-up to investigate clinical manifestations and progression of the disease (Morgan et al . [ 38 ]). Participants were seen routinely every three months for investigation and treatment if they were sick. This cohort provided important information including the survival times of HIV-infected individuals in subSaharan Africa which, unexpectedly, were not dissimilar to those described in high-income countries.

In the late 1990s, the Unit contributed significantly to the understanding of the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, showing that the prevalent HIV-1 subtypes circulating were A and D (Yirrell et al . [ 85 ]; Kaleebu et al . [ 18 ]). In late 1999, when MRC participated in the first HIV vaccine trial in Africa, there was intense debate as to whether using a subtype B-based vaccine in a region with diverse subtypes was ethical and scientifically justifiable (Mugerwa et al . [ 42 ]).

At the same time, a cohort of HIV-1-infected adults was established in Entebbe (Entebbe Cohort) to undertake a randomized trial of a polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine, in an effort to counter the impact of an important opportunistic infection (French et al . [ 14 ]). The cohort was to provide valuable information on the management of HIV and associated opportunistic infections in the pre-ART era (French et al . [ 15 ]; Watera et al . [ 82 ]). Investigations on tuberculosis–HIV interactions were initiated, such as a trial of prednisolone on HIV-associated tuberculosis, which revealed that prednisolone resulted in increased incidence of HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma (Elliott et al . [ 11 ]).

The rise of non-communicable disease is a major challenge in subSaharan Africa. The Unit began collaborations with various partners in the mid-1990s. This work provided some key insights into the impact of HIV and other factors on the risk of cancer in Uganda (Newton et al . [ 54 ]). Research in this area has been expanded and diversified over the last half decade, as non-communicable diseases have grown in relative importance as a cause of morbidity and mortality in low-income countries.

We continued to observe changes in reported sexual behaviour, especially among young people, who were adopting safer sex practices, but risky sexual behaviours increased in the middle-aged and older adults (Kamali et al . [ 22 ]; Biraro et al . [ 6 ]; Shafer et al . [ 78 ]).

While evidence for an association between HIV infection and the presence of other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) was consistent in many studies (Darrow et al . [ 9 ]; Kreiss et al . [ 27 ]; Plummer et al . [ 63 ]), it was recognised that those STDs could just be a marker for sexual behaviour. A landmark study – the Masaka Intervention Trial – was a community randomized trial which aimed at determining the effectiveness of a behavioural change intervention through information, education and communication (IEC) alone or in combination with improved STD management on HIV transmission. There was no difference between intervention arms in the incidence of HIV (Kamali et al . [ 23 ]), but the experience gained from this trial was a stepping stone for future clinical and prevention trials.

During this period, the natural history cohort generated the first data on survival time in rural African populations, showing that survival with HIV in Africa was broadly similar to that in industrialised countries (Morgan et al . [ 39 ]). These data contributed to global estimates and projections of HIV infections. Natural history cohort data also showed that in women who became pregnant, CD4 cell count decline was significantly faster after pregnancy than before (Paal et al . [ 57 ]); that malaria had little detrimental effect on risk of death among HIV-infected people (Quigley et al . [ 64 ]); and that fertility is reduced from the earliest asymptomatic stage of HIV infection as a result of both a reduced incidence of recognised pregnancy and a increased fetal loss (Ross et al . [ 67 ]).

Results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in HIV-1-infected people in the Entebbe cohort showed no benefit in preventing pneumococcal disease in this population (French et al . [ 14 ]). In contrast, studies in the Entebbe cohort showed that co-trimoxazole prophylaxis reduced HIV mortality by 23% and reduced rates of malaria by 68% (Watera et al . [ 82 ]). The Entebbe cohort provided opportunities to confirm the existence of cross-clade cellular immune responses (McAdam et al . [ 35 ]; Rutebemberwa et al . [ 69 ]). We demonstrated that cellular immune responses to the core parts of the virus correlated with slower disease progression (Serwanga et al . [ 77 ]) and that disease progression differed between HIV-1 subtypes A and D (Kaleebu et al . [ 19 ], [ 20 ]). There was no evidence that helminth infection was associated with faster HIV progression (Brown et al . [ 7 ]), contrary to widely advocated hypothesis on the potential effects of helminth-induced T-helper (Th)2-induced immunological bias.

A major development during this decade was the introduction of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) in Uganda in 2004, to treat people with HIV. Our focus changed to studying HIV-1-infected patients on treatment and to design studies that could lead to simpler approaches to deliver ART. Using data from our cohorts, we provided feedback on the effectiveness of the ARV roll-out in Uganda. We also contributed to social and behavioural studies in the ART era, including adherence studies and cost effectiveness analyses of ART delivery strategies (Seeley et al . [ 75 ]; Russell & Seeley [ 68 ]; Lara et al . [ 29 ]; Mbonye et al . [ 33 ]).

The contribution of high-risk populations such as truck drivers, fishing communities and commercial sex workers to the epidemic was already recognised, especially along the trans-African highway. The programme contributed studies on sexual networks and behaviours (Pickering et al . 1997a , b ; Gryseels et al . [ 16 ]).

The Unit took part in other important clinical trials that included the DART (multicentre trial) and the Jinja trials, looking at simple ways of delivering ART; these showed that ART could be delivered safely using minimal laboratory monitoring and that structured treatment interruption regimens were not appropriate (DART Trial Team [ 10 ]). The Jinja trial showed that home-based ART delivery using trained lay workers was effective (Jaffar et al . [ 17 ]; Woodd et al . [ 84 ]). These two studies had a significant impact on the roll-out of ART in resource limited settings. Another was the cryptococcal disease prophylactic trial, which showed that systemic cryotococcal disease can be prevented reliably and cost-effectively through oral medication with fluconazole (Parkes-Ratanshi et al . [ 59 ]). The ARROW trial, completed in 2009, revealed that ART can be delivered to children with minimal laboratory monitoring (ARROW Trial team [ 1 ]).

The Unit was part of the UK Microbicide Development Programme that conducted a number of microbicide trials including the large phase III trial of PRO2000 which, however, did not show benefit in prevention of HIV transmission (McCormack et al . [ 37 ]). This decade also saw the initiation of long-term collaboration with the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI). This partnership has helped build our capacity to conduct HIV vaccine trials including the conduct of two phase I vaccine trials in Masaka, but also to prepare cohorts for phase III efficacy trials (Ruzagira et al . [ 70 ]).

Our work gradually became a major source of data on ART drug resistance, including provision of data on HIV-transmitted drug resistance, with low to moderate resistance, as defined by WHO, reported in different populations (Ndembi et al . [ 51 ], [ 53 ]). Further capacity was built to study drug resistance, with the basic sciences laboratories becoming the national and regional HIV drug resistance reference laboratories. These activities have allowed us to make a contribution to understanding of the development of resistance among those infected with HIV subtypes A and D (Lyagoba et al . [ 30 ]; Ndembi et al . [ 52 ]).

In 2001, work on the Entebbe Mother and Baby Study began. Addressing the hypothesis that maternal helminth infection might influence the infant response to BCG, the study was designed as a trial of anthelmintic treatment during pregnancy. In fact, at age one year, no effect of the intervention on responses to mycobacterial antigens was observed, but treatment of maternal hookworm resulted in reduced Th2 responses to tetanus antigens (Webb et al . [ 83 ]). In addition, there was striking evidence that maternal worm infections protect against eczema in childhood and that treatment of maternal worms results in increased incidence of eczema (Elliott et al . [ 12 ]; Mpairwe et al . [ 40 ], [ 41 ]). These results led to a broadening of the remit of the coinfection work, to explore the wider effects of chronic immunomodulating infections on human immunity and disease patterns and of maternal infections on infant immune responses.

2009–present

While our studies in the rural population continued to provide encouraging evidence that HIV incidence is in decline, particularly since early 2000, a reversal was seen in some age groups. The epidemic was shifting demographically to encompass married couples and older age groups. The infection rates in some high-risk populations, such as those living in fishing communities around Lake Victoria and commercial sex workers, had reached alarming proportions (Asiki et al . [ 2 ]; Seeley et al . [ 76 ]; Vandepitte et al . [ 80 ]). However, with the introduction of ART, survival of HIV-1-positive persons has also improved dramatically, and HIV has become a chronic condition with both individual and societal consequences. This has reduced mortality in our cohorts and resulted in a rising HIV prevalence as infected people survive longer. Hence, our focus during this period is changing the face of the epidemic with an emphasis on HIV prevention research, especially in key populations, and on managing HIV as a chronic disease. Interestingly, we showed that contrary to common belief and despite the fact that many people in high-risk populations are highly mobile, they still had high retention rates and could be suitable for intervention studies (Asiki et al . [ 2 ]; McArthur et al . [ 36 ]).

To understand the main sources of HIV infections, we took a multidisciplinary approach that involved identifying HIV transmission networks and linkages using molecular virology combined with epidemiology and social science. Similar approaches within the high-risk groups have shown transmission networks and linkages (Ssemwanga et al . [ 79 ]; Nazziwa et al . [ 50 ]) and observed that most of the transmissions occurring in the fishing communities come from individuals who have been infected for some time rather than incident cases.

We have therefore initiated studies to investigate factors limiting access to HIV prevention interventions and to assess the feasibility of conducting HIV combination interventions in fishing communities in Uganda. These pilot studies will inform the design of effectiveness trials of combination prevention in key populations and hard-to-reach communities.

In an effort to tackle the needs of the fishing communities, we are working regionally with other partners and have initiated the Lake Victoria Fishing Consortium, allowing a broader approach to intervention and health system research. Research in high-risk populations has allowed us to make contributions in other areas such as STDs, where we reported Neisseria gonorrhoea resistance to ciprofloxacin (Vandepitte et al . [ 81 ]); host immunological factors associated with resistance to HIV infection in highly exposed seronegative individuals (Pala et al . [ 58 ]); and rates of HIV-1 superinfection (Redd et al . [ 65 ]).

Studies of HIV across the life course are generating important data on the impact of HIV in people over 50 years living with HIV, who face particular challenges and face stigma because the infection is seen as a young persons' disease (Kuteesa et al . [ 28 ]; Nyirenda et al . [ 56 ]). Children/young people living with HIV have different problems, such as adherence and disclosure (Bernays et al . [ 5 ]; Kawuma et al . [ 24 ]).

In 2012, we became part of the International Partnership on Microbicides (IPM) by participating in a microbicide phase III programme evaluating the safety and efficacy of dapivirine (NNRTI) vaginal ring in preventing HIV-1 among sexually active HIV-negative women. We also successfully completed a phase I HIV vaccine trial in Masaka using Ad35-GRIN and F4co adjuvanted with AS01B/AS01E.

We follow one of the longest treatment cohorts in Africa where many participants have been on ART for more than 10 years and were initiated on different first-line regimens. This provides an opportunity to describe the long-term safety and toxicity of ART and factors associated with the development of drug resistance. We have been part of a number of other multicentre clinical studies such as START (Babiker et al . [ 4 ]), SPARTAC (Fidler et al . [ 13 ]) and SALIF; the latter is a phase 3b trial which will give data on a novel fixed dose (TDF/3TC/ Rilpivirine) combination, which could provide a much needed alternative to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) based first-line regimen for Africa. Soon to be completed is the COSTOP, a study looking at the safety of discontinuing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis among HIV-infected adults on ART in Uganda; the results will have important policy implications. Among children, continuing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis after 96 weeks of ART was beneficial compared to stopping prophylaxis, with fewer hospitalizations for both malaria and infection not related to malaria (Bwakura-Dangarembizi et al . [ 8 ]).

The partnerships, infrastructure and multidisciplinary approach to research developed over the 25 years in the Unit are now being used to expand activities in order to address important research questions related to non-communicable diseases. These research questions include the epidemiology and genetics of communicable and non-communicable diseases, whose understanding is important to address the limited data on the burden and risk factors for non-communicable diseases in subSaharan Africa. This work is beginning to generate important information (Maher et al . [ 31 ]; Asiki et al . [ 3 ]; Murphy et al . 2013a , b , [ 48 ]; Riha et al . [ 66 ]).

A health systems research project was set-up in rural, semi-rural and urban settings in both Uganda and Tanzania (Peck et al . [ 60 ]) which plans to move into interventions research. Our research into mental health problems has expanded to include studies of psychiatric complications associated with HIV/AIDS where we see high rates of major depressive disorders (Kinyanda et al . [ 26 ]).

The results of the Entebbe Mother and Baby Study regarding helminths and allergy-related diseases have led directly to the development of a new intervention trial, the Lake Victoria Island Intervention Study on Worms and Allergy-related diseases (LaVIISWA). This is a cluster-randomised trial of intensive versus standard intervention against helminth infection, undertaken in island communities where the prevalence and intensity of schistosomiasis are particularly high.

As summarised above, MRC/UVRI has made significant contributions to HIV research over the 25 years. The initial years were aimed at understanding the new epidemic in a rural African setting and later in other high-risk groups. The later years allowed us to contribute knowledge to newer interventions and disease interactions. Our comparative advantage has been the multidisciplinary approach to our research and the longitudinal data and specimens. In response to the changing epidemic, we have also broadened our activities to non-communicable diseases and other areas.

Capacity building

Capacity building – both in terms of people and infrastructure – has been an important part of our mission right from the start. This has helped establish us as an internationally recognised centre for research on HIV and other communicable diseases. The outcome of this process is a highly productive research Unit, influencing local and international policy and scientific thinking. The Unit has also played an important role in the capacity building for UVRI that includes training of staff, creating an academic environment including opportunities for short and long courses, seminars, supervision of staff and provision of laboratory space, among others (Figures 4 and 5 ). We have also supported the construction of a new clinic, training building, laboratories and other infrastructure. Over the years, we have created strong collaborations with various universities including Makerere University. More recently, the Makerere University UVRI (MUII) programme, of which we are a partner, has further strengthened our links to the University sector in Uganda. In the past 25 years, we supported 44 PhD students and 74 MSc students. Some of these have gone on to become leaders in their field within the Unit and at other places in Uganda and elsewhere.

Bioinformatics training being conducted at the main site in Entebbe, 2013.

Immunology staff working on the BD LSR II flow cytometer.

HIV will remain a health challenge for some years to come; this epidemic remains our major focus, and we will continue with cutting edge research, taking advantage of our multidisciplinary approach and the exceptional international collaborations.

We are in a strong position to contribute to vaccine development and trials by virtue of our excellent laboratory facilities, our collaborations and our work on other factors that may influence and impair the immune response to vaccines in tropical or resource-poor settings.

We have ongoing non-communicable disease research including mental health, especially as it relates to infectious diseases, and working in partnerships, this will be an area of continued interest. New opportunities in genotyping and bioinformatics provide new avenues to understand the relationship between genetics and infections, non-communicable diseases and responses to vaccines. Indeed, two of our major cohorts have available data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

We have initiated health systems and implementation research and have important regional collaborations in this field. We consider this as a key cross-cutting area in which to build capacity. There are other areas the MRC may contribute, such as maternal and child health and neglected diseases.

In all areas, we will make it a priority to build more human capacity to have more senior researchers as future leaders. To remain competitive, we will continue to value and strengthen partnerships and collaborations, including strengthening our links with UVRI and regional universities. This has, indeed, been 25 Years of Research Excellence through Partnerships.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all past and present staff of the MRC/UVRI. Special thanks go to the previous Directors of the Unit, namely Daan Mulder, Jimmy Whitworth and Heiner Grosskurth. We also acknowledge some of the key individuals involved in the initiation of this collaboration: Jane Kengeya-Kayondo, Sylvester Sempala, Paul Kasozi Kazenga, Ruhakana Rugunda, Sam Okware, Andrew Nunn, James Gowans, Peter Smith, Keith MacAdam and David Bradley. We thank Dermot Maher for his contribution. We wish to acknowledge Robert Newton who has contributed to the drafting of this article. We acknowledge the communities we have worked with over the years, especially study participants. We acknowledge the many partners and scientific advisors we have worked with including funders, Governments and Non-Governmental organizations. This has all been possible as a result of the funding by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement, The Wellcome Trust and many other funders.

- ARROW Trial team. Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring and first-line antiretroviral therapy strategies in African children with HIV (ARROW): a 5-year open-label randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1391–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62198-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, et al. HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87:511–515. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046805. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asiki G, Murphy G, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, et al. The general population cohort in rural south-western Uganda: a platform for communicable and non-communicable disease studies. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42:129–141. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys234. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babiker AG, Emery S, Fätkenheuer G, et al. Considerations in the rationale, design and methods of the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) study. Clinical Trials. 2013;10:S5–S36. doi: 10.1177/1740774512440342. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernays S, Seeley J, Rhodes T. Mupambireyi Z. What am I ‘living’ with? Growing up with HIV in Uganda and Zimbabwe. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12189. in press. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Biraro S, Shafer L, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Is sexual risk taking behaviour changing in rural south-west Uganda? Behaviour trends in a rural population cohort 1993–2006. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:i3–i11. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033928. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown M, Kizza M, Watera C, et al. Helminth infection is not associated with faster progression of HIV disease in coinfected adults in Uganda. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;190:1869–1879. doi: 10.1086/425042. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Kendall L, Bakeera-Kitaka S, et al. A randomized trial of prolonged co-trimoxazole in HIV-Infected children in Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:41–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214901. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Darrow WW, Echenberg DF, Jaffe HW, et al. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in homosexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:479–483. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.479. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DART Trial Team. Fixed duration interruptions are inferior to continuous treatment in African adults starting therapy with CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/μl. AIDS. 2008;22:237–247. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2d760. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott AM, Luzze H, Quigley MA, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Use of Prednisolone as an Adjunct to Treatment in HIV-1 – Associated Pleural Tuberculosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;190:869–878. doi: 10.1086/422257. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott AM, Mpairwe H, Quigley MA, et al. Helminth infection during pregnancy and development of infantile eczema. JAMA. 2005;294:2028–2034. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2032-c. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fidler S, Porter K, Ewings F, et al. Short-course antiretroviral therapy in primary HIV infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:207–217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110039. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- French N, Nakiyingi J, Carpenter L, et al. 23–valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults: double-blind, randomised and placebo controlled trial. The Lancet. 2000;355:2106–2111. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02377-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- French N, Nakiyingi J, Lugada E, Watera C, Whitworth JA. Gilks CF. Increasing rates of malarial fever with deteriorating immune status in HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults. AIDS. 2001;15:899–906. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gryseels M, Pool R. Nnalusiba B. Women who sell sex in a Ugandan trading town: life histories, survival strategies and risk. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00027-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. The Lancet. 2010;374:2080–2089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61674-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaleebu P, Orth JW, Hamilton L, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV type 1 in a rural community in southwest Uganda. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2000;16:393–401. doi: 10.1089/088922200309052. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaleebu P, Ross A, Morgan D, et al. Relationship between HIV-1 Env subtypes A and D and disease progression in a rural Ugandan cohort. AIDS. 2001;15:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaleebu P, French N, Mahe C, et al. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 envelope subtypes A and D on disease progression in a large cohort of HIV-1—positive persons in Uganda. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;185:1244–1250. doi: 10.1086/340130. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamali A, Seeley JA, Nunn AJ, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Ruberantwari A. Mulder DW. The orphan problem: experience of a sub-Saharan Africa rural population in the AIDS epidemic. AIDS Care. 1996;8:509–516. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125470. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamali A, Carpenter LM, Whitworth JAG, Pool R, Ruberantwari A. Ojwiya A. Seven-year trends in HIV-1 infection rates, and changes in sexual behaviour, among adults in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2000;14:427–434. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00017. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamali A, Quigley M, Nakiyingi J, et al. Syndromic management of sexually-transmitted infections and behaviour change interventions on transmission of HIV-1 in rural Uganda: a community randomised trial. The Lancet. 2003;361:645–652. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12598-6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kawuma R, Bernays S, Siu GE, Rhodes T. Seeley J. ‘Children will always be children’: exploring perceptions and experiences of children living with HIV who may not take their treatment and why they may not tell. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2014;13:189–195. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2014.927778. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kengeya-Kayondo J-F, Kamali A, Nunn AJ, Ruberantwari A, Wagner H-UH. Mulder DW. Incidence of HIV-1 infection in adults and socio-demographic characteristics of seroconverters in a rural population in Uganda: 1990–1994. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;25:1077–1082. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.5.1077. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kinyanda E, Hoskins S, Nakku J, Nawaz S. Patel V. Prevalence and risk factors of major depressive disorder in HIV/AIDS as seen in semi-urban Entebbe district, Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-205. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kreiss J, Carael M. Meheus A. Role of sexually transmitted diseases in transmitting human immunodeficiency virus. Genitourinary Medicine. 1988;64:1–2. doi: 10.1136/sti.64.1.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuteesa MO, Seeley J, Cumming RG. Negin J. Older people living with HIV in Uganda: understanding their experience and needs. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2012;11:295–305. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.754829. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lara AM, Kigozi J, Amurwon J, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of clinically driven versus routine laboratory monitoring of antiretroviral therapy in Uganda and Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033672. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyagoba F, Dunn DT, Pillay D, et al. Evolution of drug resistance during 48 weeks of zidovudine/lamivudine/tenofovir in the absence of real-time viral load monitoring. JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55:277–283. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ea0df8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maher D, Waswa L, Baisley K, Karabarinde A, Unwin N. Grosskurth H. Distribution of hyperglycaemia and related cardiovascular disease risk factors in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;40:160–171. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq156. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malamba SS, Wagner H-U, Maude G, et al. Risk factors for HIV-1 infection in adults in a rural Ugandan community: a case–control study. AIDS. 1994;8:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199402000-00014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mbonye M, Seeley J, Ssembajja F, Birungi J. Jaffar S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Jinja, Uganda: a six-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078243. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mbulaiteye S, Mahe C, Whitworth J, et al. Declining HIV-1 incidence and associated prevalence over 10 years in a rural population in south-west Uganda: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2002;360:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09331-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McAdam S, Kaleebu P, Krausa P, et al. Cross-clade recognition of p55 by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1998;12:571–579. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McArthur M, Birdthistle I, Seeley J, Mpendo J. Asiki G. How HIV diagnosis and disclosure affect sexual behavior and relationships in Ugandan fishing communities. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23:1125–1137. doi: 10.1177/1049732313495327. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCormack S, Ramjee G, Kamali A, et al. PRO2000 vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection (Microbicides Development Programme 301): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. The Lancet. 2010;376:1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61086-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan D, Malamba SS, Maude GH, et al. An HIV-1 natural history cohort and survival times in rural Uganda. AIDS. 1997;11:633–640. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan D, Mahe C, Mayanja B, Okongo JM, Lubega R. Whitworth JA. HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries? AIDS. 2002;16:597–603. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mpairwe H, Webb EL, Muhangi L, et al. Anthelminthic treatment during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of infantile eczema: randomised-controlled trial results. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2011;22:305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01122.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mpairwe H, Ndibazza J, Webb EL, et al. Maternal hookworm modifies risk factors for childhood eczema: results from a birth cohort in Uganda. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2014;25:481–488. doi: 10.1111/pai.12251. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mugerwa RD, Kaleebu P, Mugyenyi P, et al. First trial of the HIV-1 vaccine in Africa: Ugandan experience. British Medical Journal. 2002;324:226–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.226. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mulder DW, Nunn AJ, Wagner H-U, Kamali A. Kengeya-Kayondo JF. HIV-1 incidence and HIV-1-associated mortality in a rural Ugandan population cohort. AIDS. 1994;8:87–92. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199401000-00013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mulder D, Nunn A, Kamali A. Kengeya-Kayondo J. Decreasing HIV-1 seroprevalence in young adults in a rural Ugandan cohort. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:833–836. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.833. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mulder DW, Nunn A, Kamali A. Kengeya-Kayondo JF. Post-natal incidence of HIV-1 infection among children in a rural Ugandan population: no evidence for transmission other than mother to child. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1996;1:81–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-12.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy GA, Asiki G, Ekoru K, et al. Sociodemographic distribution of non-communicable disease risk factors in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013a;42:1740–1753. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt184. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy GA, Asiki G, Young EH, et al. Cardiometabolic Risk in a Rural Ugandan Population. Diabetes Care. 2013b;36:e143. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0739. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy GA, Asiki G, Nsubuga RN, et al. The use of anthropometric measures for cardiometabolic risk identification in a rural African population. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:e64–e65. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2096. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nakibinge S, Maher D, Katende J, Kamali A, Grosskurth H. Seeley J. Community engagement in health research: two decades of experience from a research project on HIV in rural Uganda. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2009;14:190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02207.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nazziwa J, Njai H, Ndembi N, et al. HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance and evidence of transmission clusters among recently infected antiretroviral naïve individuals from Ugandan fishing communities of Lake Victoria. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2013;29:788–795. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0123. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ndembi N, Lyagoba F, Nanteza B, et al. Transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance surveillance among newly HIV type 1-diagnosed women attending an antenatal clinic in Entebbe, Uganda. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2008;24:889–895. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0317. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ndembi N, Goodall RL, Dunn DT, et al. Viral rebound and emergence of drug resistance in the absence of viral load testing: a randomized comparison between zidovudine-lamivudine plus nevirapine and zidovudine-lamivudine plus abacavir. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;201:106–113. doi: 10.1086/648590. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ndembi N, Hamers RL, Sigaloff KC, et al. Transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance among newly HIV-1 diagnosed young individuals in Kampala. AIDS. 2011;25:905–910. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328346260f. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newton R, Ziegler J, Beral V, et al. A case–control study of human immunodeficiency virus infection and cancer in adults and children residing in Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Cancer. 2001;92:622–627. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<622::aid-ijc1256>3.0.co;2-k. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nunn AJ, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Malamba SS, Seeley JA. Mulder DW. Risk factors for HIV-1 infection in adults in a rural Ugandan community: a population study. AIDS. 1994;8:81–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199401000-00012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nyirenda M, Newell ML, Mugisha J, et al. Health, wellbeing, and disability among older people infected or affected by HIV in Uganda and South Africa. Global Health Action. 2013;6:19201. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19201. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paal LVd, Shafer LA, Mayanja BN, Whitworth JA. Grosskurth H. Effect of pregnancy on HIV disease progression and survival among women in rural Uganda. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2007;12:920–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.001873.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pala P, Serwanga J, Watera C, et al. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the T cell response to HIV in uninfected Ugandans exposed or unexposed to HIV infected partners. Journal of Virology. 2013;87:9053–9063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00721-13. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parkes-Ratanshi R, Wakeham K, Levin J, et al. Primary prophylaxis of cryptococcal disease with fluconazole in HIV-positive Ugandan adults: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2011;11:933–941. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70245-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peck R, Mghamba J, Vanobberghen F, et al. Preparedness of Tanzanian health facilities for outpatient primary care of hypertension and diabetes: a cross-sectional survey. The Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:e285–e292. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70033-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pickering H, Okongo M, Bwanika K, Nnalusiba B. Whitworth J. Sexual behaviour in a fishing community on Lake Victoria, Uganda. Health Transition Review. 1997a;7:13–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pickering H, Okongo M, Ojwiya A, Yirrell D. Whitworth J. Sexual networks in Uganda: mixing patterns between a trading town, its rural hinterland and a nearby fishing village. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 1997b;8:495–500. doi: 10.1258/0956462971920640. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1991;163:233–239. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Quigley MA, Hewitt K, Mayanja B, et al. The effect of malaria on mortality in a cohort of HIV-infected Ugandan adults. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2005;10:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01461.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Redd AD, Ssemwanga D, Vandepitte J, et al. Rates of HIV-1 superinfection and primary HIV-1 infection are similar in female sex workers in Uganda. AIDS. 2014;500:14–00349. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000365. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riha J, Karabarinde A, Ssenyomo G, et al. Urbanicity and Lifestyle Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Diseases in Rural Uganda: a Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11:e1001683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001683. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross A, Van der Paal L, Lubega R, Mayanja BN, Shafer LA. Whitworth J. HIV-1 disease progression and fertility: the incidence of recognized pregnancy and pregnancy outcome in Uganda. AIDS. 2004;18:799–804. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell S. Seeley J. The transition to living with HIV as a chronic condition in rural Uganda: working to create order and control when on antiretroviral therapy. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.039. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutebemberwa A, Auma B, Gilmour J, et al. HIV type 1-specific inter-and intrasubtype cellular immune responses in HIV type 1-infected Ugandans. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2004;20:763–771. doi: 10.1089/0889222041524643. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruzagira E, Wandiembe S, Abaasa A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HIV in a rural community-based HIV vaccine preparedness cohort in Masaka, Uganda. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020684. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley J, Wagner U, Mulemwa J, Kengeya-Kayondo J. Mulder D. The development of a community-based HIV/AIDS counselling service in a rural area in Uganda. AIDS Care. 1991;3:207–217. doi: 10.1080/09540129108253064. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley JA, Kengeya-Kayondo JF. Mulder DW. Community-based HIV/AIDS research–Whither community participation? Unsolved problems in a research programme in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90282-u. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley J, Kajura E, Bachengana C, Okongo M, Wagner U. Mulder D. The extended family and support for people with AIDS in a rural population in south west Uganda: a safety net with holes? AIDS Care. 1993;5:117–122. doi: 10.1080/09540129308258589. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley JA, Malamba SS, Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, Kengeya-Kayondo JF. Barton TG. Socioeconomic status, gender, and risk of HIV-1 Infection in a rural community in South West Uganda. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1994;8:78–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley J, Russell S, Khana K, Ezati E, King R. Bunnell R. Sex after ART: sexual partnerships established by HIV-infected persons taking anti-retroviral therapy in Eastern Uganda. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2009;11:703–716. doi: 10.1080/13691050903003897. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeley J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, et al. High HIV incidence and socio-behavioral risk patterns in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39:433–439. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318251555d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Serwanga J, Shafer LA, Pimego E, et al. Host HLA B* allele-associated multi-clade Gag T-cell recognition correlates with slow HIV-1 disease progression in antiretroviral therapy-naive Ugandans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004188. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shafer LA, Nsubuga RN, Seeley J, Levin J. Grosskurth H. Examining the components of population-level sexual behavior trends from 1993 to 2007 in an open Ugandan cohort. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38:697–704. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318214e42e. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ssemwanga D, Kapaata A, Lyagoba F, et al. Low drug resistance levels among drug-naive individuals with recent HIV type 1 infection in a rural clinical cohort in southwestern Uganda. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2012;28:1784–1787. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0090. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandepitte J, Weiss HA, Bukenya J, et al. Alcohol use, mycoplasma genitalium, and other STIs associated with HIV incidence among women at high risk in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;62:119–126. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182777167. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandepitte J, Hughes P, Matovu G, Bukenya J, Grosskurth H. Lewis DA. High prevalence of ciprofloxacin-resistant gonorrhea among female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda (2008–2009) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2014;41:233–237. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000099. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watera C, Todd J, Muwonge R, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-1-infected adults attending an HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda. JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42:373–378. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221679.14445.1b. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Webb EL, Mawa PA, Ndibazza J, et al. Effect of single-dose anthelmintic treatment during pregnancy on an infant's response to immunisation and on susceptibility to infectious diseases in infancy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2011;377:52–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61457-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woodd SL, Grosskurth H, Levin J, et al. Home-based versus clinic-based care for patients starting antiretroviral therapy with low CD4+ cell counts: findings from a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS. 2014;28:569–576. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000056. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yirrell DL, Pickering H, Palmarini G, et al. Molecular epidemiological analysis of HIV in sexual networks in Uganda. AIDS. 1998;12:285–290. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199803000-00006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (390.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Uganda Research Unit is an internationally recognized centre of excellence for research and training.

Mar 31, 2022 · Activities range from virology, and immunology to clinical studies and intervention trials, epidemiological studies, behavioural research and health economy studies, supported by strong statistical and laboratory services and a community development programme. Find out more about the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit.

Medical Research Council; Uganda Virus Research Institute; MRC Uganda; Contact. MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit PO Box 49 Entebbe Plot 51-59 Nakiwogo Road Uganda Telephone: (+256) (0) 417704000 / 0312262911 Email: [email protected] Gallery. Gallery

Professor Moffat Nyirenda has been announced as the new Director of the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Uganda Research Unit (MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit). He will take over the role from Professor Pontiano Kaleebu on 1 April 2024.

May 5, 2022 · 05 May 2022, Entebbe The MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit has today unveiled a state-of-the-art clinical research facility in Entebbe to support successful conduct of clinical studies that can make significant contributions to science, policy and practice in Uganda. The facility commissioning ceremony was presided over by the Hon. Dr ...

Jan 15, 2024 · Professor Moffat Nyirenda has been announced as the new Director of the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Uganda Research Unit (MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit). He will take over the role from Professor Pontiano Kaleebu on 1 April 2024.

Medical Research Council Programme on AIDS. Telephone number: +256 41 320272/32004 Fax Number: +256 41 321137 Physical address Uganda Virus Research Institute (MRC/UVRI) P.O. Box 49, Entebbe Uganda

Oct 29, 2014 · This year 2014, we celebrate 25 years of the Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute (MRC/UVRI) Uganda Research Unit on AIDS. On 12th December 1988, the initial memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Uganda and British governments was signed, leading to the establishment of MRC/UVRI.

Find 163 researchers and browse 7 departments, publications, full-texts, contact details and general information related to Medical Research Council / Uganda Virus Research Institute | Entebbe ...

May 11, 2022 · The MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit has unveiled a new state-of-the-art clinical research facility in Entebbe to further boost its contributions to science, policy and practice in Uganda.