Biographical sketch of Helen Keller, taken from pamphlet published by American Foundation for the Ov... 1952 — Image 1

HELEN KELLER

/>/>! k'slf;. ■ : s ft f a t*> ft

(Taken from a pamphlet published by American Foundation for Overseas Blind, Inc,)

The story of Helen Keller is the story of a child suddenly shut off from the world at the age of nineteen months, and of her slow and hard but victorious fight to re-enter it. Through the years, the little deaf and blind mute has become the woman of the gifted pen, writing and speaking and incessantly working, toward the betterment of others. Her story is, in brief,^that of a halfwild creature become a highly intelligent and sensitive citizen with a definite place in the history of our time. She was born, a normal child, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, on June 27, i860, Helen was suddenly bereft of sight and hearing by an illness in babyhood. The disease had been diagnosed as brain fever. According to popular theory of the time this disease was believed to leave its victim an idiot. Strong and healthy physically, she grew into childhood, wild and unruly, with little real understanding of what went on around her. It was when Helen was nearly seven years old that her teacher, Anne Sullivan, a girl of twenty, was brought to her from Perkins Institution, Boston, Massachusetts, This was arranged through the sympathetic interest of Alexander Graham Bell, whose advice had been sought by the parents. After•that^time, the two - teacher and pupil - were inseparable, until the death of Anne Sullivan in 1936, Anne Sullivan had undertaken a task that called for inexhaustible patience and courage. The little children at Perkins Institution had made a doll for her to take to Helen, She began her training with that, trying to connect objects with letters by spelling M d-o-l-l n in the manual alphabet into the child’s hand, Helen quickly learned to make the letters correctly, but did not know that she was spelling a word, or that words existed. In the days that followed she learned to spell in this uncomprehending way a great many more words, One day she and her teacher were standing beside_the outdoor pump while someone was drawing water. Miss Sullivan put Helen’s hand under the spout. As the cool water gushed 0V 6 r ® ne hand, she spelled into the other the word ”w-a-t-e~r” first slowly, then rapidly. Suddenly, the signals crossed Helen’s consciousness with a meaning. She knew that ’’water” meant the wonderful cool something flowing over her hand. Quickly she stooped and touched the earth and demanded its letter-name, and by nightfall of that day she had learned thirty words. That was the beginning of Keller’s education. In quick succession she mastered^the alphabet, both manual and in raised print for the blind, and gained facility

Privacy policy

Terms of use, add to private list, move to another list.

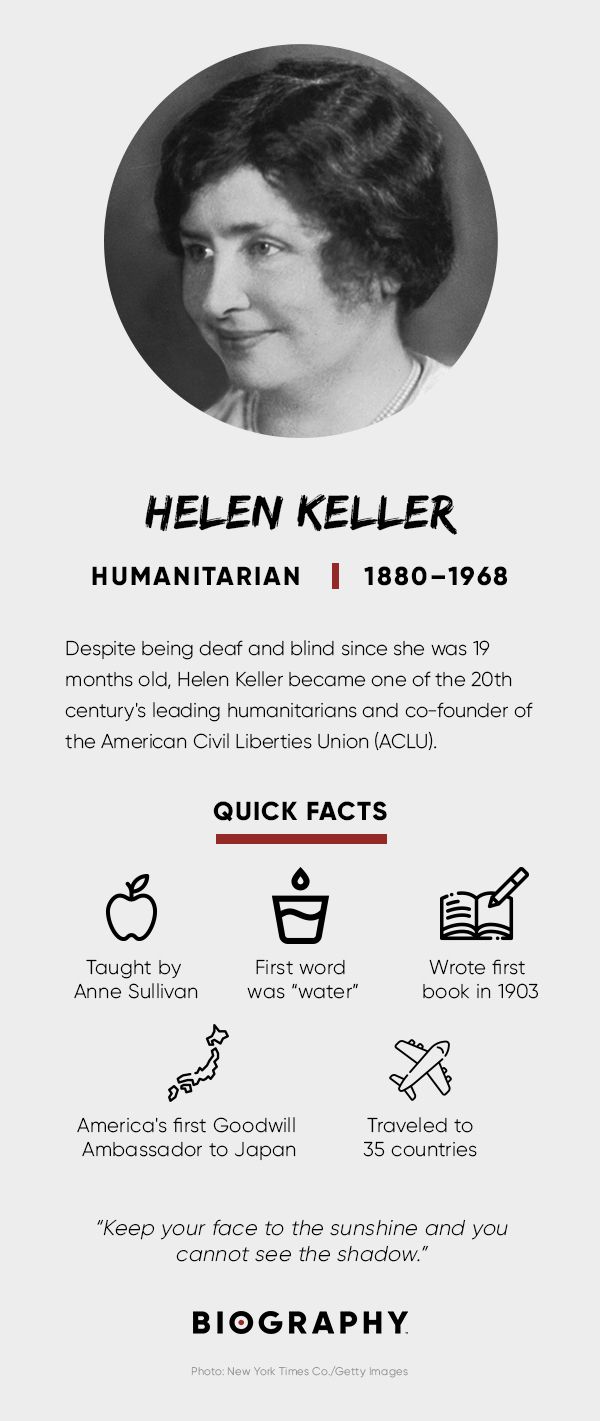

Helen Keller

American educator Helen Keller overcame the adversity of being blind and deaf to become one of the 20th century's leading humanitarians as well as co-founder of the ACLU.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

(1880-1968)

Who Was Helen Keller?

Early life and family, loss of sight and hearing, keller's teacher, anne sullivan, 'the story of my life', social activism, 'the miracle worker' movie, awards and honors, quick facts:.

Helen Keller was an American educator, advocate for the blind and deaf and co-founder of the ACLU. Stricken by an illness at the age of 2, Keller was left blind and deaf. Beginning in 1887, Keller's teacher, Anne Sullivan, helped her make tremendous progress with her ability to communicate, and Keller went on to college, graduating in 1904. During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments.

Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Keller was the first of two daughters born to Arthur H. Keller and Katherine Adams Keller. Keller's father had served as an officer in the Confederate Army during the Civil War . She also had two older stepbrothers.

The family was not particularly wealthy and earned income from their cotton plantation. Later, Arthur became the editor of a weekly local newspaper, the North Alabamian .

Keller was born with her senses of sight and hearing, and started speaking when she was just 6 months old. She started walking at the age of 1.

Keller lost both her sight and hearing at just 19 months old. In 1882, she contracted an illness — called "brain fever" by the family doctor — that produced a high body temperature. The true nature of the illness remains a mystery today, though some experts believe it might have been scarlet fever or meningitis.

Within a few days after the fever broke, Keller's mother noticed that her daughter didn't show any reaction when the dinner bell was rung, or when a hand was waved in front of her face.

As Keller grew into childhood, she developed a limited method of communication with her companion, Martha Washington, the young daughter of the family cook. The two had created a type of sign language. By the time Keller was 7, they had invented more than 60 signs to communicate with each other.

During this time, Keller had also become very wild and unruly. She would kick and scream when angry, and giggle uncontrollably when happy. She tormented Martha and inflicted raging tantrums on her parents. Many family relatives felt she should be institutionalized.

Keller worked with her teacher Anne Sullivan for 49 years, from 1887 until Sullivan's death in 1936. In 1932, Sullivan experienced health problems and lost her eyesight completely. A young woman named Polly Thomson, who had begun working as a secretary for Keller and Sullivan in 1914, became Keller's constant companion upon Sullivan's death.

Looking for answers and inspiration, Keller's mother came across a travelogue by Charles Dickens, American Notes, in 1886. She read of the successful education of another deaf and blind child, Laura Bridgman, and soon dispatched Keller and her father to Baltimore, Maryland to see specialist Dr. J. Julian Chisolm.

After examining Keller, Chisolm recommended that she see Alexander Graham Bell , the inventor of the telephone, who was working with deaf children at the time. Bell met with Keller and her parents, and suggested that they travel to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston, Massachusetts.

There, the family met with the school's director, Michael Anaganos. He suggested Keller work with one of the institute's most recent graduates, Sullivan.

On March 3, 1887, Sullivan went to Keller's home in Alabama and immediately went to work. She began by teaching six-year-old Keller finger spelling, starting with the word "doll," to help Keller understand the gift of a doll she had brought along. Other words would follow.

At first, Keller was curious, then defiant, refusing to cooperate with Sullivan's instruction. When Keller did cooperate, Sullivan could tell that she wasn't making the connection between the objects and the letters spelled out in her hand. Sullivan kept working at it, forcing Keller to go through the regimen.

As Keller's frustration grew, the tantrums increased. Finally, Sullivan demanded that she and Keller be isolated from the rest of the family for a time, so that Keller could concentrate only on Sullivan's instruction. They moved to a cottage on the plantation.

In a dramatic struggle, Sullivan taught Keller the word "water"; she helped her make the connection between the object and the letters by taking Keller out to the water pump, and placing Keller's hand under the spout. While Sullivan moved the lever to flush cool water over Keller's hand, she spelled out the word w-a-t-e-r on Keller's other hand. Keller understood and repeated the word in Sullivan's hand. She then pounded the ground, demanding to know its "letter name." Sullivan followed her, spelling out the word into her hand. Keller moved to other objects with Sullivan in tow. By nightfall, she had learned 30 words.

In 1905, Sullivan married John Macy, an instructor at Harvard University, a social critic and a prominent socialist. After the marriage, Sullivan continued to be Keller's guide and mentor. When Keller went to live with the Macys, they both initially gave Keller their undivided attention. Gradually, however, Anne and John became distant to each other, as Anne's devotion to Keller continued unabated. After several years, the couple separated, though were never divorced.

In 1890, Keller began speech classes at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf in Boston. She would toil for 25 years to learn to speak so that others could understand her.

From 1894 to 1896, Keller attended the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City. There, she worked on improving her communication skills and studied regular academic subjects.

Around this time, Keller became determined to attend college. In 1896, she attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, a preparatory school for women.

As her story became known to the general public, Keller began to meet famous and influential people. One of them was the writer Mark Twain , who was very impressed with her. They became friends. Twain introduced her to his friend Henry H. Rogers, a Standard Oil executive.

Rogers was so impressed with Keller's talent, drive and determination that he agreed to pay for her to attend Radcliffe College. There, she was accompanied by Sullivan, who sat by her side to interpret lectures and texts. By this time, Keller had mastered several methods of communication, including touch-lip reading, Braille, speech, typing and finger-spelling.

Keller graduated, cum laude, from Radcliffe College in 1904, at the age of 24.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S HELEN KELLER FACT CARD

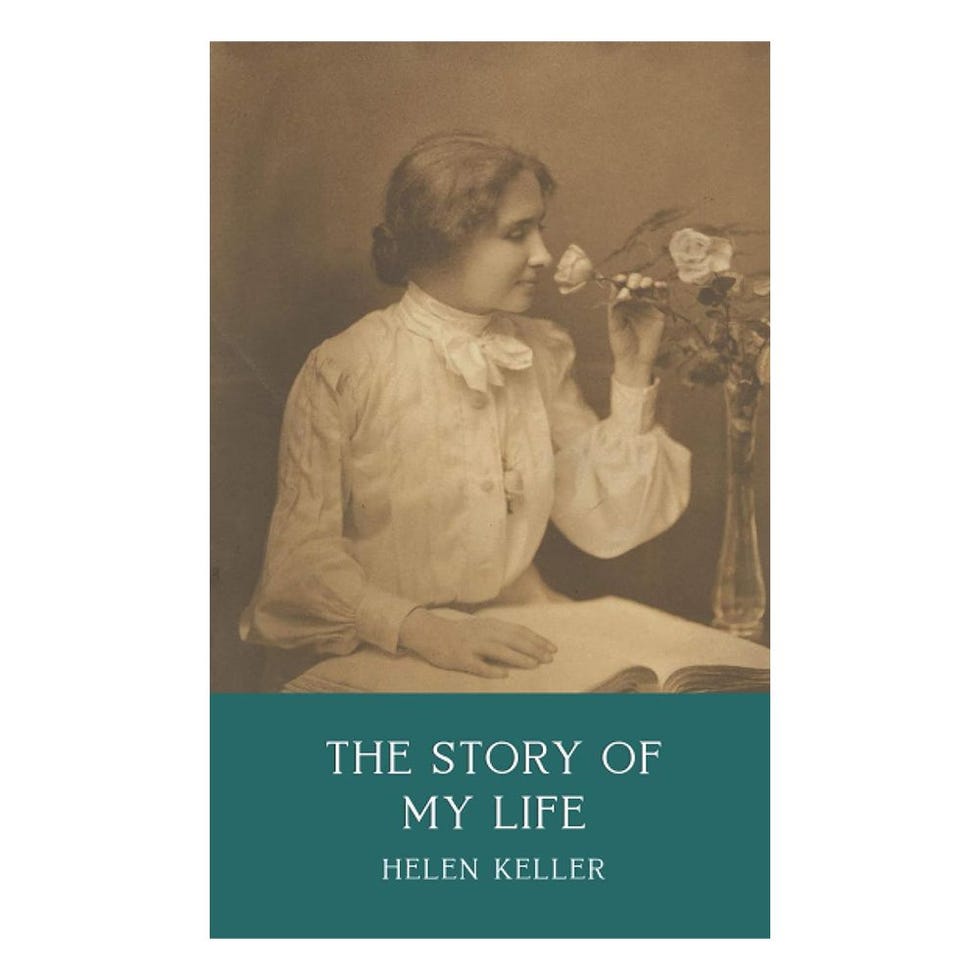

With the help of Sullivan and Macy, Sullivan's future husband, Keller wrote her first book, The Story of My Life . Published in 1905, the memoirs covered Keller's transformation from childhood to 21-year-old college student.

'The Story of My Life' by Helen Keller

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Keller tackled social and political issues, including women's suffrage, pacifism, birth control and socialism.

After college, Keller set out to learn more about the world and how she could help improve the lives of others. News of her story spread beyond Massachusetts and New England. Keller became a well-known celebrity and lecturer by sharing her experiences with audiences, and working on behalf of others living with disabilities. She testified before Congress, strongly advocating to improve the welfare of blind people.

In 1915, along with renowned city planner George Kessler, she co-founded Helen Keller International to combat the causes and consequences of blindness and malnutrition. In 1920, she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union .

When the American Federation for the Blind was established in 1921, Keller had an effective national outlet for her efforts. She became a member in 1924, and participated in many campaigns to raise awareness, money and support for the blind. She also joined other organizations dedicated to helping those less fortunate, including the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund (later called the American Braille Press).

Soon after she graduated from college, Keller became a member of the Socialist Party, most likely due in part to her friendship with John Macy. Between 1909 and 1921, she wrote several articles about socialism and supported Eugene Debs, a Socialist Party presidential candidate. Her series of essays on socialism, entitled "Out of the Dark," described her views on socialism and world affairs.

It was during this time that Keller first experienced public prejudice about her disabilities. For most of her life, the press had been overwhelmingly supportive of her, praising her courage and intelligence. But after she expressed her socialist views, some criticized her by calling attention to her disabilities. One newspaper, the Brooklyn Eagle , wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development."

In 1946, Keller was appointed counselor of international relations for the American Foundation of Overseas Blind. Between 1946 and 1957, she traveled to 35 countries on five continents.

In 1955, at age 75, Keller embarked on the longest and most grueling trip of her life: a 40,000-mile, five-month trek across Asia. Through her many speeches and appearances, she brought inspiration and encouragement to millions of people.

Keller's autobiography, The Story of My Life , was used as the basis for 1957 television drama The Miracle Worker .

In 1959, the story was developed into a Broadway play of the same title, starring Patty Duke as Keller and Anne Bancroft as Sullivan. The two actresses also performed those roles in the 1962 award-winning film version of the play.

During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments, including the Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal in 1936, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, and election to the Women's Hall of Fame in 1965.

Keller also received honorary doctoral degrees from Temple University and Harvard University and from the universities of Glasgow, Scotland; Berlin, Germany; Delhi, India; and Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. She was named an Honorary Fellow of the Educational Institute of Scotland.

Keller died in her sleep on June 1, 1968, just a few weeks before her 88th birthday. Keller suffered a series of strokes in 1961 and spent the remaining years of her life at her home in Connecticut.

During her remarkable life, Keller stood as a powerful example of how determination, hard work, and imagination can allow an individual to triumph over adversity. By overcoming difficult conditions with a great deal of persistence, she grew into a respected and world-renowned activist who labored for the betterment of others.

FULL NAME: Helen Adams Keller BORN: June 27, 1880 BIRTHPLACE: Tuscumbia, AL DIED: June 1, 1968 ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Cancer

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Keep your face to the sunshine and you cannot see the shadow.

- One can never consent to creep when one feels an impulse to soar.

- Remember, no effort that we make to attain something beautiful is ever lost. Sometime, somewhere, somehow we shall find that which we seek.

- Gradually from naming an object we advance step by step until we have traversed the vast distance between our first stammered syllable and the sweep of thought in a line of Shakespeare.

- If it is true that the violin is the most perfect of musical instruments, then Greek is the violin of human thought.

- A happy life consists not in the absence, but in the mastery of hardships.

- The two greatest characters in the 19th century are Napoleon and Helen Keller. Napoleon tried to conquer the world by physical force and failed. Helen tried to conquer the world by power of mind — and succeeded!” (Mark Twain)

- The bulk of the world’s knowledge is an imaginary construction.

- We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond the senses.

- [T]he mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!

- It is more difficult to teach ignorance to think than to teach an intelligent blind man to see the grandeur of Niagara.

- Everything has its wonders, even darkness and silence, and I learn, whatever state I may be in, therein to be content.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Suffragettes

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

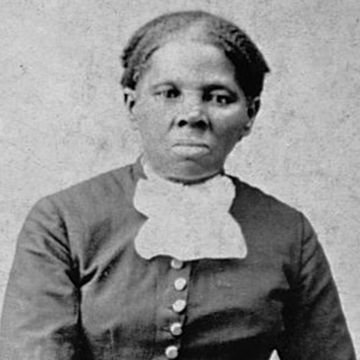

Harriet Tubman

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Emmeline Pankhurst

Carrie Chapman Catt

Kate Sheppard

Emily Davison

Molly Brown

Character Sketch of Helen Keller from “The Story of My Life” by Helen Keller

Helen Keller, the extraordinary individual immortalized in “The Story of My Life,” authored by Helen Keller herself, is a testament to the indomitable human spirit. Born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Helen faced formidable challenges early in life. At the tender age of 19 months, an illness—likely scarlet fever or meningitis—robbed her of both sight and hearing, plunging her into a world of silence and darkness.

Despite these profound obstacles, Helen Keller’s character emerges as one of resilience, intellect, and profound determination. The narrative unfolds as she recounts her journey from a world of isolation and confusion to one of enlightenment and accomplishment, illustrating the transformative power of education and the human will.

The early years of Helen’s life were tumultuous, marked by frustration and a sense of alienation. Her inability to communicate left her in a state of perpetual isolation, as she struggled to comprehend the world around her. However, the turning point came with the arrival of Anne Sullivan, a dedicated teacher and companion. Anne’s unwavering commitment to unlocking Helen’s potential forms a pivotal aspect of Helen’s character sketch.

Helen’s relationship with Anne Sullivan was more than that of a student and teacher; it was a deep, symbiotic bond. Anne’s innovative methods, including finger-spelling words into Helen’s hand, opened a gateway to language for the young girl. The breakthrough moment at the water pump, where Helen made the connection between the flowing water and the corresponding word, symbolized not only the acquisition of language but the unlocking of Helen’s intellectual prowess.

As Helen Keller delves into her formative years, her character exhibits an insatiable thirst for knowledge. Despite her sensory limitations, she excelled academically and developed a voracious appetite for literature and learning. Her journey through formal education, from Radcliffe College to mastering multiple languages, showcased her intellectual capabilities and determination to overcome perceived limitations.

Beyond academics, Helen’s character shines through in her advocacy for the rights of individuals with disabilities. She became a trailblazer in breaking down societal barriers, challenging preconceived notions about the capabilities of those with sensory impairments. Her contributions extended to writing, lecturing, and championing social causes, making her an influential figure in disability rights.

Courage is another defining trait of Helen Keller’s character. In a world where most take communication for granted, she faced it as a formidable challenge. Helen’s determination to surmount her limitations and contribute meaningfully to society required immense courage. Her journey was not only an individual triumph but an inspiration for countless others facing similar challenges.

Helen Keller’s character sketch is incomplete without acknowledging her literary accomplishments. “The Story of My Life” stands as a testament to her eloquence and ability to articulate the complexities of her experiences. Her writings are imbued with introspection, wit, and a profound understanding of the human condition, transcending the boundaries of sensory perception.

In conclusion, Helen Keller emerges as a luminous figure in the annals of human history—a symbol of triumph over adversity, an intellectual powerhouse, and a trailblazer in the fight for equal rights. Her character, as depicted in “The Story of My Life,” continues to inspire generations, underscoring the resilience of the human spirit and the transformative power of education and determination.

Rahul Kumar is a passionate educator, writer, and subject matter expert in the field of education and professional development. As an author on CoursesXpert, Rahul Kumar’s articles cover a wide range of topics, from various courses, educational and career guidance.

Related Posts

Character sketch of maddie from the story “peggy” class 10th, character sketch of lencho from the story “a letter to god” class 10th, character sketch of aunt jane in never never nest by cedric mount.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when she was 19 months old.

Oct 21, 2024 · Helen Keller Helen Keller with a Braille book, c. 1904. (more) She wrote of her life in several books, including The Story of My Life (1903), Optimism (1903), The World I Live In (1908), Light in My Darkness and My Religion (1927), Helen Keller’s Journal (1938), and The Open Door (1957).

A biographical sketch of Helen Keller written for the Associated Press May 1, 1932 Viewer displaying image 1 of 13 Zoom In ctrl+alt+Z Zoom Out ctrl+alt+O Fit to Width ctrl+alt+D Fit to Height ctrl+alt+H Previous Image ctrl+alt+P Next Image ctrl+alt+N Full Screen ctrl+alt+F

4» • * After the death of ”Teacher” in 1936 Helen Keller moved to the country near New York City, In 1946 ? during her trip of investigation in Europe, the white frame house in which she had. been living and where she had collected so many mementos of a rich and busy life burned to the groundo On her return, friends rallied to her cause and helped to rebuilt the house, an exact ...

2 * • • HELEN KELLER />/>! k'slf;. : s ft f a t*> ft (Taken from a pamphlet published by American Foundation for Overseas Blind, Inc,) The story of Helen Keller is the story of a child suddenly shut off from the world at the age of nineteen months, and of her slow and hard but victorious fight to re-enter it.

Dec 22, 2023 · Helen Keller, a remarkable figure in history, overcame profound challenges to become an enduring symbol of resilience, determination, and the triumph of the human spirit. Born in 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Helen’s life was forever altered at the age of 19 months when an illness left her deaf and blind.

Go here to watch a video about Helen Keller. Occupation: Activist; Born: June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama ; Died: June 1, 1968 in Arcan Ridge, Easton, Connecticut ; Best known for: Accomplishing much despite being both deaf and blind. Biography: Where did Helen Keller grow up? Helen Keller was born on June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama.

Jul 17, 2024 · DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S HELEN KELLER FACT CARD 'The Story of My Life' With the help of Sullivan and Macy, Sullivan's future husband, Keller wrote her first book, The Story of My Life. Published in ...

Dec 6, 2023 · Helen Keller, the extraordinary individual immortalized in “The Story of My Life,” authored by Helen Keller herself, is a testament to the indomitable human spirit. Born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Helen faced formidable challenges early in life.

Helen Adams Keller was an American writer and speaker.She was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama in 1880. Her father was Arthur H. Keller and her mother was Kate Adams Keller. [1] When she was nineteen months old, she became sick and lost her eyesight and hearing.