Experiment 4 - Particle Shadow Velocimetry

1. Introduction

The most common flow velocity measurement device is probably the Pitot-static probe (used in Experiment 3). This is a rugged and inexpensive device that in many situations can be used to give accurate and reliable velocity measurements. However, Pitot-static probes cannot measure velocity fluctuations associated with turbulence or unsteadiness. Furthermore, the time average velocities they can measure are inaccurate in regions where the flow is highly turbulent, reversing or of unknown direction (as in the center of the wake of a circular cylinder). Unfortunately such regions are often of the greatest engineering interest.

More sophisticated techniques can be used to obtain such information. An increasingly commonly used technique is particle image velocimetry. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) is a non-intrusive measurement that utilizes a predefined laser plane to illuminate tiny particles dispersed throughout the fluid in quick succession. The change in particle position between successive images can be used to determine the velocity of each particle in the images and therefore provide estimate of the flow field over the entire imaging area. This technique has the advantage of providing measurement over a (possibly) large area in a short period of time. The disadvantages are the cost of the equipment (cameras can cost upwards of $10,000 a piece and lasers routinely cost $40,000 and up), the need for optical access for both the cameras to image the flow and for the laser. One of the greatest disadvantages of modern, high-speed PIV systems is that they rely on Class IV high-power lasers. Such laser systems pose a health and safety risk to their users and to their surroundings as they can damage tissues, cause skin burn, or in extreme cases, lead to the loss of sight.

Partially as a response to the health and safety risks associated with PIV lasers, researchers at Penn State University proposed an alternative but similar method to PIV: the Particle Shadow Velocimetry (PSV). PSV relies on the use of a generalized light source, such as bright LEDs, which is significantly less expensive than high-speed powerful lasers. In this configuration, the light travels along the optical axis of the camera and the measurement volume (i.e. flow field of interest) is located between the light source and the camera, see Figure 2. As its name suggests, shadows of the flow seeding particles are captured in the images obtained by the camera - you might imagine the result similar to watching a sunset over the horizon when objects, such as trees, will turn into silhouettes. Using the proper image processing algorithms, the images from the camera can be inverted such that they will be identical to images obtained by PIV systems. Therefore, PSV can offer the same capabilities as PIV at a significantly reduced cost while it can also eliminate the high risks associated with using Class IV lasers. In this experiment, you will be using a high-speed PSV system to measure the flow field in a closed-circuit water tunnel in the wake of a cylinder.

Basic principles

While you may be familiar with the operating principles of PIV, the operating principles of PSV will be introduced in the following paragraphs. Your experiment will use the same principles to obtain flow velocity data. The working principle of particle shadow velocimetry is to capture the shadows of particles in the flow to allow us to track their position between successively acquired images. To do so, the flow is imaged by one or two high speed cameras in order to accurately measure the flow velocity components. There are generally two types of PSV (or also PIV) setups: 2-component and 3-component (also known as stereo PSV or PIV). 2-component PSV uses only one camera and yields 2 of the velocity components within a plane, whereas stereo PSV uses two cameras and gives you the full 3 components of velocity over a thin volume of fluid. Stereo imaging works in much the same way as how our eyes allow us to accurately perceive distance. Stereo PSV is more complex to implement and process however, due the addition of the second camera, so for this lab we will focus solely on a 2-component PSV procedure.

A typical 2-D PSV setup can be seen in Figure 2 below. The light source is located on the right, where an RGB (red, green, blue) LED (light emitting diode) light source is used. The light passes through the flow where flow seeding particles are present. The particles block the path of the light from the LED as it propagates to the lens and then to the CCD (charge-coupled device) sensor of the high-speed camera. In the case of a PSV setup, the focal plane and focal depth of the lens will determine the region of the fluid where measurement data is obtained. Only in this thin volume of fluid will the shadows of the particles will be observed (i.e. sharp in the image) by the camera. One component of the optical setup is missing from Figure 2, which is a light diffusing sheet between the focal plane and the LED light. In the current experiment, a light diffusing sheet is responsible to evenly distribute the light arriving from the LED light to the camera.

Particles As mentioned above, tiny particles must be present in the flow for a measurement to be made. These are referred to as seed particles, or just seeding. It is important that these particles be small enough to accurately follow all the movements of the flow. That way, when we measure the velocity of the particles, we are also measuring the velocity of the flow. These particles are either dissolved or aerosolized in the flow. Note that, even in well seeded flows, the particles form only a minuscule fraction of the volume of the fluid. They therefore have no significant effect upon the flow. In this experiment, you will be using Cospheric gray microspheres with a 250-300 micrometer in diameter as seed particles whose density is identical to that of water, therefore, they are buoyant in the water tunnel used in this experiment.

Light Source

In this PSV experiment, you will be using a time-pulsed RGB LED light source (seen in Figure 4b), custom designed and built by INNSI for PSV applications. The light pulses are timed such that they occur during the time window when the camera is recording the images. This increases the signal-to-noise ratio of particle shadows seen in the pictures.

The focal plane of the optical system (camera+lens) will be located so that it lays in a streamwise plane perpendicular to the cylinder span, along the centerline of the test-section. The high-speed camera will be placed perpendicular to the test section volume as shown in Figure 4b.

A calibration plate with rows and columns of shaded circles (3.2 mm in diameter and spaced 15 mm apart) is used to precisely focus the camera and to determine the measurement location. An example of such plate can be seen in Figure 4a and 4b. The calibration plate is placed into the test section and the camera lens is focused to the front surface of the calibration plate. A built-in software can then accurately determine the relative position of the camera with respect to the focal plane by acquiring images of the calibration plate and triangulating the position of each white circle. An optical calibration is then obtained which is the relation between spatial units and pixels, i.e. a calibration constant of pixels/mm is found. From this, the observed particle displacement measured in pixels is related to particle, or flow, speed by the software you will be using.

Signals and signal processing Once the high speed camera is precisely focused, it is synchronized with the pulses of the LED light so that when you look at two successive images, the particles will have moved a couple of pixels. This particle shift between each set of successive set of images is important for post processing because the processing code breaks down the images into smaller pieces called interrogation windows. Within these interrogation windows, the processing code will compute the cross-correlation between the interrogation windows of two consecutive images and calculate the most likely displacement for the entire group of particles inside the interrogation window. Knowing the time delay between the two consecutive images, the velocity can be determined. It is important to note that you want as many seed particles as possible while still being able to distinguish between the particles for optimum results.

Once the cross-correlation between a pair of interrogation windows has been completely calculated, the window shifts over or down while usually still maintaining a 50% overlap with the previous interrogation window. This overlap increases processing time, but it allows for a greatly reduced uncertainty in stitching all of the interrogation windows back into the full image with calculated velocity vectors. The processing results in the entire velocity field in the plane of the laser sheet. With a single camera, the velocity field measured is two-dimensional (like in your experiment). For 3D velocity measurements, a second camera is required and the technique becomes stereo-PSV. From this velocity field, one can extract information about the flow structures, wake profiles, and vorticity field. You are encouraged to search for applications of PIV and PSV measurements in the aerospace and ocean engineering community before your experiment so that you can get a wider picture of this method's use and applicability.

B. Cylinder model A circular cylinder with 0.75 inches in diameter is mounted close to the mid height of the test section, see Figure 8. The cylinder is manufactured from aluminum and spans the entire test section width (that means, of course, that the ends of the cylinder are in the boundary layers on the side walls of the water tunnel test section).

Figure 8. The cylinder in the test section of the water tunnel.

You will employ a 1c2D PSV system (1 camera, 2D velocity components) for this experiment, see Figure 9. The system uses an LM2X-DMHP-RGB type 3-Color LED Light Source made by Innovative Scientific Solutions, Inc. The LED light will be pulsed at 500 ms intervals for a time period of 180 microseconds.

The camera is a Photron FASTCAM SA1.1 with a 50mm focal length and an aperture of 8.0. The camera features a 1024 x 1024 pixel sensor and is capable of 3,600 fps at full frame and up to 500,000fps when using partial frame. In this experiment, the cameras will image the flow at 200Hz over an area of approximately 10 cm x 10 cm. For this experiment, the 1024 pixels x 1024 pixels image is broken down into 64 pixels x 64 pixels interrogation areas.

The fluid motion will be highlighted using gray particles called microspheres. These particles are manufactured by Cospheric to have a diameter between 250 and 300 microns and a density of 1 gram/ccm.

The system will be calibrated prior to your laboratory session. However, the PSV system does not require the recalibration (unlike PIV) as long as the camera and lens settings (focal distance and aperture) is not modified. Taking a benefit of this feature, the camera and the light source has been mounted on a table with a traversing system responsible for moving the light source and the camera in the streamwise direction. You will therefore have the freedom to choose where to take data with the PSV system within the entire volume of the test section.

Figure 9. The overall view of the PSV setup in the water tunnel.

- Connect to the pump controller using the Connect button. Once successful, you will be prompted the "Connected" message in the status indicator.

- Set a desired speed in Hz (anywhere between 6 Hz and 30 Hz) and click "Set Pump Speed". The pump speed will stabilize in 10 seconds, the GUI will countdown from 10 to 0 s and will prompt you the Current speed in Hz and the current flow speed in m/s.

- You can stop the pump by clicking the STOP button. Make sure you stop the pump once you finished acquiring data and/or at the end of your lab session.

You will have access to the water tunnel using PTZ (pan tilt zoom) cameras. You are encouraged to take screenshots of the apparatus as they are operated for your logbook and to move the PTZ camera around to get a better view of the equipment and the measurement apparatus.

F. Instrumentation for Measuring the Properties of Water Unlike air, the properties of water are remarkably constant with pressure (an increase in the atmospheric pressure by a factor of 100 would only have a 0.5% effect on density). They are however a function of temperature. You will use another Matlab GUI that obtains readings of the water temperature using a waterproof DS18B20 digital temperature sensor (see Figure 4) operated by an Arduino Uno board. According to the manufacturer, the sensor has a ±0.5℃ accuracy within the -55 and 125℃ temperature range. In Matlab, you can run the GUI by right clicking on its name ("D:\AOE3054_MatlabGUIs\MeasureWaterTemperature.mlapp") and click on Run. Once ready, click on the "Read water temperature" button, which will obtain a temperature reading, see Figure 15. The measurement takes less than a minute. Repeat the measurement as many times you need throughout your experiment.

Figure 15. Obtain water temperature using the Matlab GUI.

Tables for the density and kinematic viscosity of water can be found in numerous textbooks (e.g. Shames, 1992). The following calculator uses a quintic fit to these tables. The uncertainties in the curve fits are ±4x10 -9 m 2 s -1 and ±0.04kg m -3

A. Getting familiar with the equipment and ready for an experiment The following procedures are designed to help you get a feel for the water tunnel, the cylinder model and the PSV software. Feel free to play with the apparatus at this stage, but don't forget to record any results, thoughts, ideas or concerns in the logbook. Setting up a PSV experiment to make a measurement from scratch can take days, so don't feel frustrated if, in the space of a 2-hour 45-minute lab, the measurements don't go too quickly or the data rate is slow. You are obtaining research-quality measurements using cutting edge technology, each data set you get is a significant achievement.

For information regarding software instructions, see section 7.

- The PSV system will have already been turned on by your lab TA and will be ready for use when you arrive in the lab.

- Acquire a data set and look at the raw images. Do you see the cylinder? Do you see the particles? Are they moving with the flow?

- Export the mean velocity field and look at the magnitude of the vectors? What is the freestream velocity? What is the velocity in the wake? Do these make sense? Are they consistent with Figure 6? Discuss among the group what it shows. Also, discuss in the group where in the flow you expect the vertical component to be large.

- Try changing the flow speed using the Matlab GUI. How does speed affect the PSV measurement? Does it work just as well? Think about a good flow speed to measure at.

- Note the water temperature again. Has it changed? Will you be able to assume its constant, or will you have to re-measure it periodically? Can you estimate the cylinder Reynolds number, from the velocity measurement outside of the wake and the temperature? What flow regime shall your measurements fall based on the Reynolds number?

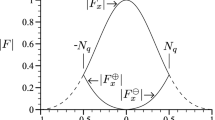

Goal 1. Design and implement a series of tests to determine the shape and form of the circular cylinder wake at the center span at a fixed Reynolds number. Suggestions. Don't forget to record and explain your choice of conditions (i.e. flow speed) and measurement locations in the logbook. If you measured wake structure in Experiment 3, at the much higher Reynolds number of the wind tunnel, measuring at some of the same streamwise locations (relative to the cylinder center and its diameter) would also provide a valuable comparison. Its usually easiest to measure the wake in a series of vertical profiles. Don't forget you can measure both vertical and horizontal velocity components. (If you measure both vertical and horizontal mean velocities at the same actual points you can determine the magnitude and direction of the mean velocity vector at each point). Analyze and plot your results as you go. Re-measure any funny looking points. Keep careful documentation of what you do, why you do it, set up characteristics, expected results, unexpected results, analysis, photos and plots in the electronic lab book as you proceed. Ideally, you would want to measure the velocity upstream of the cylinder (since it is the freestream velocity you will use to normalize all your results). You can traverse the light and camera to image the flow upstream of the cylinder to do so. Make you are carefully documenting where you take this measurement. Will this measurement be contaminated by the presence of the cylinder? How so? Could you use the continuity equation to work out the free-stream velocity? How does that compare to the data the Matlab GUI prompts you? Analysis suggestions for later. Basically, you want to present and describe your mean velocity flow field as clearly as possible, reveal the shape and form of the flow, and compare that with Experiment 3 or any theoretical model you are aware of. When post-processing your data, try using the mean velocity field information to visualize the streamlines of the flow. Mean velocity profiles show the time average shape of the flow. Look at the individual images. They show what the flow looks like at each instant. Linking these views is good discussion.

Goal 2. Design and implement a series of tests to examine the flow over the front of the cylinder at center-span a set Reynolds number, and compare with ideal flow theory. Suggestions. The issue here can be "how good is the ideal flow solution over the front of the cylinder, since the flow here isn't separated". Record and explain your choice of conditions for your measurement (i.e. flow speed) and measurement locations in the logbook. Choose your measurement locations to make the comparison with the theory as straightforward as possible. Don't forget you can measure both horizontal and vertical velocity components. Determine how you can obtain vorticity from the velocity field. Checking the freestream velocity outside the wake of the cylinder might be a wise thing to do since knowing the free stream velocity is critical to compare with the theory. Analyze and plot your results as you go. Re-measure any funny looking points. Keep careful documentation of what you do, why you do it, set up characteristics, expected results, unexpected results, analysis, photos and plots in the electronic lab book as you proceed. Analysis should include uncertainty estimates for all results.

Goal 3. Identify the flow regimes the cylinder generates in its wake by mapping out the flow's Reynolds number, Strouhal number and induced drag. Suggestions. Calculate the Strouhal number using instantaneous velocity data, calculate the drag coefficient using time-averaged velocity data. Plot the results as a function of Reynolds number and compare it to other measurement results (see Ref 3). How does your results differ and why? How does the turbulence intensities differ from the data presented in the literature? How does the Strouhal number change with flow speed? How does this compare to data presented in the literature?

Time management The group should leave few minutes at the end of the lab period for discussion and to check that everybody has everything they need. You will need to use your own cloud server (such as Google Drive or Dropbox, etc.) to transport your data from the lab computer running the experiment to your own device. Make sure you have access to a cloud service. Within your cloud, you will need 350 Mb of free space per one instantaneous data set. For time-averaged data, you will need 10 Mb of free space. Prior to your experiment, m ake sure you prepare enough space in your cloud and include the link to your cloud provider in your logbook. Use a web browser on the laboratory computer during your lab session to upload your data to your cloud. Alternatively, you may use a file sharing website, such as this one, to transfer your data from the PSV computer to you own. Keep in mind that data transfer might take up to 15 minutes.

Title page As detailed in Appendix 1 .

Introduction Begin this section by stating logical objectives that fit what your data has shown you.

Then explain in summary form what was done to achieve the objectives. You could follow this with a background discussion of what PSV is and what sources of error there are and/or a description of the basis of ideal flow theory for the circular cylinder. If you can draw on any material additional to the manual that is good. Finishing with a summary of the layout of the rest of the report would work well.

Apparatus and Instrumentation This section is probably easiest to write in two parts (though that is not required), one dealing with the water tunnel and the other with the PSV. In describing the water tunnel give all details relevant to the experiment (e.g. closed circuit, contraction ratio, dimensions and shape of test section, flow quality in the empty section at test conditions, flow speed range and control etc.) You might include here some of your measurements (e.g. of the inflow velocity) if they are relevant to describing the characteristics of the facility, as opposed to the cylinder flow. Also describe the model, its dimensions, its method of mounting, its vertical position when mounted, the traverse its accuracy etc. In describing the PSV, explain what type of system was used, its optical characteristics, the components of the system, the location of the measurement volume in the test section, software etc..

To describe all of this, diagrams and/or labeled photographs, screenshots are very necessary. Take what you like from the manual, but be sure to reference it. You will have to show at least one figure showing the water tunnel test section, model, and model mount in relation to the PSV measurement area. Make sure your figure(s) are dimensioned properly. Include your uncertainties in primary measurements in this section

Results and Discussion A good way to begin is to briefly state what measurements were made and at what locations and conditions. You should also include here definitions of the statistical quantities plotted (e.g. mean velocity, mean vorticity etc...), and explanations of how their uncertainties were calculated and what those uncertainties were. You should reference a table (copied out of your Excel file) or appendix containing the uncertainty calculation. Early on in the results and discussion (or even in the apparatus and Instrumentation) you need to define a coordinate system, and any key normalizing variables, using a diagram and description in the text, e.g. "The coordinate system to be used in presenting results is shown in figure ??. Coordinate x is measured downstream from the cylinder center, y vertically upwards from that center and z , directed so as to complete a right-handed system is measured from the center span location. Velocity components u and v are defined in the directions x and y . Distances will in general be normalized on the ??? and velocities on the approach velocity measured at x=??, y=??, z=?? )".

If you have them, now would be a good time to introduce any flowvis pictures. Don't just describe what the static pictures show, use the pictures as a springboard to describing what you actually saw.

Next introduce your profile plots - the kind of wording suggested in experiment 3 will work just fine here. Now describe in detail the plots and error estimates. Then discuss what their significance is given the goals/ objectives you have chosen (look again at the suggestions given with the goals above). One workable approach is to describe what appears on each of the plots in turn, using a separate paragraph for each, inserting sentences of discussion as you go e.g. "Figure ?? shows the profile of u RMS (normalized on free-stream velocity) plotted against y measured at x=?? and z =?? . At the limits of the profile, turbulence levels are low at about ?? and reasonably consistent with values measured in the empty test section of ?? (see AOE 3054 Course Manual, 2016, Experiment 4). Presumably these points lie outside the cylinder wake. The wake edges appear to be marked by the large increases in u RMS at around y=?? and ??. The fact that velocity fluctuations in the wake should be larger than outside is consistent with turbulence being present in...".

Make sure your results and discussion include (and justify) the conclusions you want to make and that those conclusions connect with your objectives (if not, change the discussion or the objectives).

Conclusions Begin this section with one or two sentences describing what you did. Then draw your conclusions, each numbered and starting on a separate line. Each conclusion should summarize an important piece of information that was revealed or taught by the experiment. Make sure the conclusions cover all the points addressed by your objectives and all the important points of your discussion. Note that no new material should appear in the conclusions. It should be possible to write them by simply lifting key sentences from the rest of your report (mostly the Results and Discussion). Also note that the conclusions should stand by themselves, though you may refer to the figures if you wish.

- Bertin J.J. 2001, Aerodynamics for Engineers , 4th edition, Prentice Hall.

- Shames I. H., 1992, Mechanics of Fluids , Third Edition, McGraw Hill, New York.

- Panton R. L., 2013, Incompressible Flow, 4th edition, Wiley, New York.

Your web browser doesn't have a PDF plugin. Instead you can click here to download the PDF file.

- AOE3054_PIV_ImportInstant_2020.m : you will run this function on the 199 instantaneous velocity files to import that data into Matlab. The code will create a MAT file (whose name you will specify) with four variables:

- X and Y are the streamwise and vertical coordinates of the measurement locations. The X and Y matrices have a size of MxM.

- U and V are the velocity component matrices and will be MxMx199 matrices since you obtain components for each consecutive pair of the 200 images.

- AOE3054_PIV_ImportMean_2020.m : you will run this function on the 9 averaged quantity files to import that data into Matlab. The code will create a MAT file (whose name you will specify) with 12 variables:

- X and Y are the streamwise and vertical coordinates of the measurement locations

- U and V are the velocity components at those points

- Umag is the velocity magnitude

- stdU and stdV are the standard deviation at each point on the grid (computed over the 200 images)

- AKE and TKE are the average and total kinetic energy

- Rxx, Rxy, and Ryy are the Reynolds stresses

- Two folders containing a sample data set are provided in the ZIP file so you can test the import codes and debug your own plotting codes ahead of your experiment:

- 20HzSampleData_Instantaneous: 199 instantaneous velocity files acquired at a pump speed of 20Hz.

- 20HzSampleData_Averages: 9 averaged quantities acquired at a pump speed of 20Hz.

Particle Image Velocimetry

A Practical Guide

- © 2018

- Latest edition

- Markus Raffel ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3340-9115 0 ,

- Christian E. Willert 1 ,

- Fulvio Scarano 2 ,

- Christian J. Kähler 3 ,

- Steve T. Wereley 4 ,

- Jürgen Kompenhans 5

Institut für Aerodynamik und Strömungstechnik, Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. (DLR), Göttingen, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Institut für Antriebstechnik, Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. (DLR), Köln, Germany

Department of aerospace engineering, delft university of technology, delft, the netherlands, institut für strömungsmechanik und aerodynamik, universität der bundeswehr münchen, neubiberg, germany, department of mechanical engineering, birck nanotech center, purdue university, west lafayette, usa.

- Offers relevant theoretical background information directly supporting the practical aspects form PIV experiments

- Includes tomographic PIV method, high-velocity PIV, Micro-PIV, and accuracy assessment

- Guides researchers and engineers to design and perform their experiment successfully without requiring them to first become specialists in the field

229k Accesses

662 Citations

7 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This practical guide provides comprehensive information on PIV. The third edition extends many aspects of Particle image Velocimetry, in particular the tomographic PIV method, high-velocity PIV, Micro-PIV, and accuracy assessment.

In this book, relevant theoretical background information directly support the practical aspects associated with the planning, performance and understanding of experiments employing the PIV technique. It is primarily intended for engineers, scientists and students, who already have some basic knowledge of fluid mechanics and non-intrusive optical measurement techniques. It shall guide researchers and engineers to design and perform their experiment successfully without requiring them to first become specialists in the field. Nonetheless many of the basic properties of PIV are provided as they must be well understood before a correct interpretation of the results is possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Recent Developments in Particle Tracking Diagnostics for Turbulence Research

Comparison between optical flow and cross-correlation methods for extraction of velocity fields from particle images.

Theoretical description of PIV measurement errors

- Digital Image Recording

- tomographic PIV

- high-velocity PIV

- Statistical PIV Evaluation

- PIV Recording

- Three-Component PIV

- fluid- and aerodynamics

Table of contents (19 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Markus Raffel, Christian E. Willert, Fulvio Scarano, Christian J. Kähler, Steven T. Wereley, Jürgen Kompenhans

Physical and Technical Background

Recording techniques for piv, mathematical background of statistical piv evaluation, image evaluation methods for piv, piv uncertainty and measurement accuracy, post-processing of piv data, stereoscopic piv, techniques for 3d-piv, applications: boundary layers, applications: transonic flows, applications: helicopter aerodynamics, applications: aeroacoustic and pressure measurements, applications: flows at different temperatures, applications: micro piv, applications: stereo piv and multiplane stereo piv, applications: volumetric flow measurements, related techniques, authors and affiliations.

Markus Raffel, Jürgen Kompenhans

Christian E. Willert

Fulvio Scarano

Christian J. Kähler

Steve T. Wereley

About the authors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Particle Image Velocimetry

Book Subtitle : A Practical Guide

Authors : Markus Raffel, Christian E. Willert, Fulvio Scarano, Christian J. Kähler, Steve T. Wereley, Jürgen Kompenhans

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68852-7

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Engineering , Engineering (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-319-68851-0 Published: 13 April 2018

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-09855-1 Published: 25 December 2018

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-68852-7 Published: 03 April 2018

Edition Number : 3

Number of Pages : XXVI, 669

Number of Illustrations : 270 b/w illustrations, 164 illustrations in colour

Topics : Engineering Fluid Dynamics , Measurement Science and Instrumentation , Fluid- and Aerodynamics , Industrial Chemistry/Chemical Engineering , Signal, Image and Speech Processing , Engineering Thermodynamics, Heat and Mass Transfer

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How PIV Works

Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) is an optical experimental technique engineers use to both visualize and measure fluid flow fields (i.e., liquid or gas). A common laboratory set up for PIV is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example laboratory PIV set-up, where a camera images a laser light sheet that is illuminating a flow field seeded with particles.

As shown in Figure 1, laser sheet optics (i.e., a cylindrical lens) focus the collimated laser beam into a thin laser sheet. The laser sheet illuminates neutrally buoyant particles (i.e., seeds) that have been introduced into the flow. These small (1-100 $\mu m$) seeds both follow the flow field and effectively scatter the laser light so that they can be seen and imaged. A digital camera (directed orthogonal to the laser sheet plane) images the particles in the plane as shown in Figure 2. The velocity can be calculated by taking the displacement of the particles divided by a known time step. In general, the particles shouldn’t move too much, the flow field being images should be the same between time steps and the time should be small enough that the particles have only moved a few particle diameters.

Figure 2. Image of a flow field that was illuminated with a laser light-sheet and imaged by a camera and the mi-PIV application. The neutrally buoyant particles in the flow field appear white as they reflect the laser light.

By taking two images of the same space of a flow field a small, known time apart, the displacement of the particle position over time (i.e., velocity) can be computed.

PIV Algorithms

Instead of tracking the movement of each individual particle (known as PTV), PIV algorithms segment each of the two images into smaller images referred to as interrogation regions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Main image 1 (from Figure 2) partitioned into interrogation regions.

Basic PIV algorithms employ statistical correlation methods to identify the most likely location of a set of particles as they move within an interrogation region in the first image to an interrogation window in the second image. The “search area” is the interrogation region in the second image. The translation of a set of particles is identified by finding the change in x and y location from the first image to the second image. PIV algorithms identify the velocity of the fluid in each region by dividing this translation by the prescribed time between images.

More accurate PIV measurements result when particle movements are contained within overlapping interrogation regions, since a small search radius increases the likelihood of maintaining valid correlations (i.e., correlating the translation of the same particles). The likelihood of a poor or erroneous correlation increases as the “search area” increases. In other words, the farther you move from the particles’ initial position in the first interrogation region, the more likely you are to correlate to the wrong set of particles in the second interrogation region.

References: [1] B. L. Smith and D. R. Neal, “Particle Image Velocimetry,” Part. Image Velocim. , p. 27, 2016.

Author: Jack Elliott

Date Published: June, 2022

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Particle image velocimetry (PIV) is a non-intrusive optical flow measurement technique used to study fluid flow patterns and velocities. PIV has found widespread applications in various fields of science and engineering, including aerodynamics, combustion, oceanography, and biofluids.

The previously described conventional PIV approach is used to investigate macroscopic flow configurations, i.e. the typical length scales of such PIV experiments are in the order of 10 −2 –10 0 m. In these cases the measurement plane is defined by the light-sheet plane. The light-sheet plane has a typical thickness of 0.5–1 mm. This is by ...

Experimental arrangement for PIV in a wind tunnel. Basic principles The experimental setup of a PIV system consists of several subsystems: a flow-producing facility like a wind tunnel with its possible subsystems (e.g., an injection system to cool down the gas and an exhaust system to control the tunnel pressure).

Sep 14, 2021 · Figure 1. Fluorescent Particle Image Velocimetry Technique (courtesy of Prof. Todd Lowe from Virginia Tech) (a) Experimental Setup, (b) Animation of particle motion as acquired by PIV camera (flow direction is bottom to top), (c) PIV results for the velocity magnitude (flow direction is bottom to top ; dark triangular area in the bottom right corner is the region shielded from the flow by the ...

Particle image velocimetry (PIV) is an optical technique that employs Mie scattering from tracer particles seeded in a flow. In a typical experiment, two sequential laser pulses are used to illuminate the particles, and two matching camera frames capturing the scattered light are required for a measurement of velocity.

%PDF-1.3 %Äåòåë§ó ÐÄÆ 4 0 obj /Length 5 0 R /Filter /FlateDecode >> stream x ¥œË’ÛHv†÷xŠì +BC Á‹wí CŽq¸ÇQ¶ÃáöB ÕUÓ »© ½ð3Î#ù ...

Recent works deal with the combination of PIV data with CFD techniques, extension of PIV to large-scale wind tunnel experiments and applications ranging from sport aerodynamics to ground vehicles, from aircraft to rocket aerodynamics. Author of more than 200 publications, delivered more than 20 keynote lectures worldwide.

Jan 1, 2007 · [Show full abstract] experiments employing the PIV technique. It is primarily intended for engineers, scientists and students, who already have some basic knowledge of fluid mechanics and non ...

Dec 1, 2020 · Due to the relatively small dynamics, PIV cannot resolve all temporal and spatial scales simultaneously and the experiment must therefore be tuned to yield the desired results. The proper selection requires experience.

A common laboratory set up for PIV is depicted in Figure 1. Figure 1. Example laboratory PIV set-up, where a camera images a laser light sheet that is illuminating a flow field seeded with particles. As shown in Figure 1, laser sheet optics (i.e., a cylindrical lens) focus the collimated laser beam into a thin laser sheet.