Thinking and Analysis

Critical thinking skills.

The essence of the independent mind lies not in what it thinks, but in how it thinks. —Christopher Hitchens, author and journalist

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define critical thinking

- Describe the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to problem-solve

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to evaluate information

- Identify strategies for developing yourself as a critical thinker

Critical Thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s a “domain-general” thinking skill—not a thinking skill that’s reserved for a one subject alone or restricted to a particular subject area.

Great leaders have highly attuned critical thinking skills, and you can, too. In fact, you probably have a lot of these skills already. Of all your thinking skills, critical thinking may have the greatest value.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Activity: Self-Assess Your Critical Thinking Strategies

- Assess your basic understanding of the skills involved in critical thinking.

- Visit the Quia Critical Thinking Quiz page and click on Start Now (you don’t need to enter your name). Select the best answer for each question, and then click on Submit Answers. A score of 70 percent or better on this quiz is considering passing.

- Based on the content of the questions, do you feel you use good critical thinking strategies in college? In what ways might you improve as a critical thinker?

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination for the purpose of logically constructing reasoned perspectives.

What Is Logic, and Why Is It Important in Critical Thinking?

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community. The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him. In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

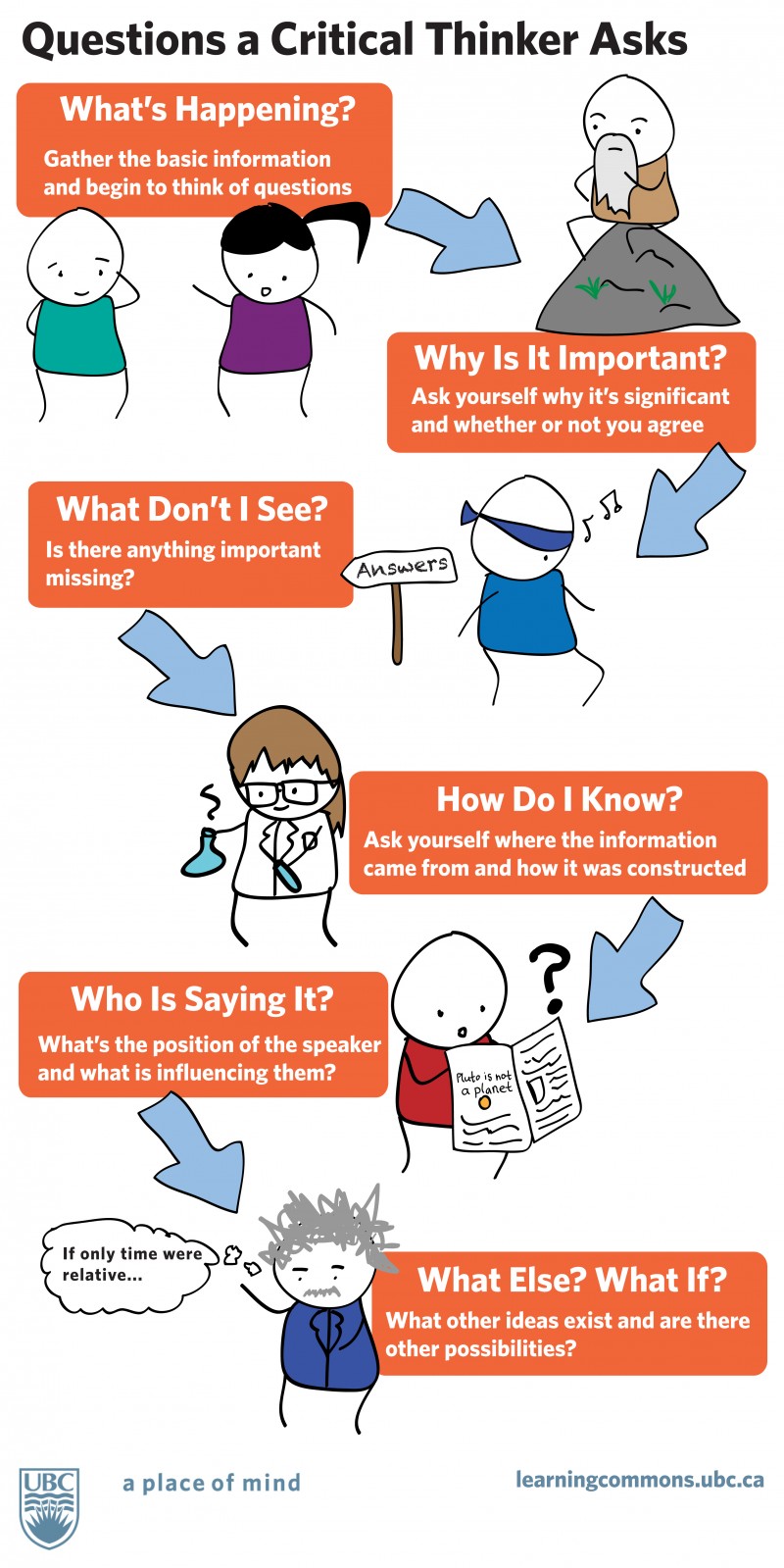

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving with Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in the relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support the roommate and help bring the relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your campus club has been languishing on account of lack of participation and funds. The new club president, though, is a marketing major and has identified some strategies to interest students in joining and supporting the club. Implementation is forthcoming.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember, too, to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker. If you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions.

Evaluating Information with Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

- Cultivate “habits of mind”

Read for Understanding Using Text Coding

When you read and take notes, use the text coding strategy . Text coding is a way of tracking your thinking while reading. It entails marking the text and recording what you are thinking either in the margins or perhaps on Post-it notes. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material.

With text coding, mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. Feel free to develop your own shorthand style when reading or taking notes. The following are a few options to consider using while coding text.

See more text coding from PBWorks and Collaborative for Teaching and Learning .

Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The following video explains this strategy.

Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

Developing Yourself As a Critical Thinker

Critical thinking is a desire to seek, patience to doubt, fondness to meditate, slowness to assert, readiness to consider, carefulness to dispose and set in order; and hatred for every kind of imposture. —Francis Bacon, philosopher

Critical thinking is a fundamental skill for college students, but it should also be a lifelong pursuit. Below are additional strategies to develop yourself as a critical thinker in college and in everyday life:

- Reflect and practice : Always reflect on what you’ve learned. Is it true all the time? How did you arrive at your conclusions?

- Use wasted time : It’s certainly important to make time for relaxing, but if you find you are indulging in too much of a good thing, think about using your time more constructively. Determine when you do your best thinking and try to learn something new during that part of the day.

- Redefine the way you see things : It can be very uninteresting to always think the same way. Challenge yourself to see familiar things in new ways. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes and consider things from a different angle or perspective. If you’re trying to solve a problem, list all your concerns: what you need in order to solve it, who can help, what some possible barriers might be, etc. It’s often possible to reframe a problem as an opportunity. Try to find a solution where there seems to be none.

- Analyze the influences on your thinking and in your life : Why do you think or feel the way you do? Analyze your influences. Think about who in your life influences you. Do you feel or react a certain way because of social convention, or because you believe it is what is expected of you? Try to break out of any molds that may be constricting you.

- Express yourself : Critical thinking also involves being able to express yourself clearly. Most important in expressing yourself clearly is stating one point at a time. You might be inclined to argue every thought, but you might have greater impact if you focus just on your main arguments. This will help others to follow your thinking clearly. For more abstract ideas, assume that your audience may not understand. Provide examples, analogies, or metaphors where you can.

- Enhance your wellness : It’s easier to think critically when you take care of your mental and physical health. Try taking 10-minute activity breaks to reach 30 to 60 minutes of physical activity each day . Try taking a break between classes and walk to the coffee shop that’s farthest away. Scheduling physical activity into your day can help lower stress and increase mental alertness. Also, do your most difficult work when you have the most energy . Think about the time of day you are most effective and have the most energy. Plan to do your most difficult work during these times. And be sure to reach out for help . If you feel you need assistance with your mental or physical health, talk to a counselor or visit a doctor.

Activity: Reflect on Critical Thinking

- Apply critical thinking strategies to your life

Directions:

- Think about someone you consider to be a critical thinker (friend, professor, historical figure, etc). What qualities does he/she have?

- Review some of the critical thinking strategies discussed on this page. Pick one strategy that makes sense to you. How can you apply this critical thinking technique to your academic work?

- Habits of mind are attitudes and beliefs that influence how you approach the world (i.e., inquiring attitude, open mind, respect for truth, etc). What is one habit of mind you would like to actively develop over the next year? How will you develop a daily practice to cultivate this habit?

- Write your responses in journal form, and submit according to your instructor’s guidelines.

The following text is an excerpt from an essay by Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, “Thinking Critically and Creatively.” In these paragraphs, Dr. Baker underscores the importance of critical thinking—the imperative of critical thinking, really—to improving as students, teachers, and researchers. The follow-up portion of this essay appears in the Creative Thinking section of this course.

Thinking Critically and Creatively

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Resources for Critical Thinking

- Glossary of Critical Thinking Terms

- Critical Thinking Self-Assessment

- Logical Fallacies Jeopardy Template

- Fallacies Files—Home

- Thinking Critically | Learning Commons

- Foundation for Critical Thinking

- To Analyze Thinking We Must Identify and Question Its Elemental Structures

- Critical Thinking in Everyday Life

Candela Citations

- Critical Thinking Skills. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of three students. Authored by : PopTech. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8tXtQp . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : http://www.oercommons.org/courses/learning-toolkit-critical-thinking/view . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Authored by : UBC Leap. Located at : https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of students putting post-its on wall. Authored by : Hector Alejandro. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7b2Ax2 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Foundations of Academic Success. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- "logike." Wordnik. n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- "Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online." Critical Thinking Gateway . St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- [email protected]

The Importance of Critical Thinking in Education | Benefits & Strategies

Article 11 Dec 2024 542

In the classroom and beyond, thinking critically can transform how students learn, solve problems, and prepare for their futures. Whether analyzing an argument, tackling a challenge, or assessing the credibility of a source, critical thinking helps students approach situations with clarity and logic.

In this article, we'll explore why fostering these skills in education is not just a benefit but a necessity. We'll also dive into practical strategies educators can use to cultivate these abilities.

Table of Content

What is critical thinking, why is critical thinking important in education, teaching strategies to foster critical thinking, real-world application of these strategies, challenges in teaching critical thinking, assessing critical thinking skills, real-life impact: a case study.

Critical thinking involves analyzing and evaluating information carefully to make thoughtful, reasoned decisions. Questioning assumptions, recognizing biases, and considering multiple perspectives before reaching conclusions is essential.

This approach differs significantly from rote memorization, which is solely about recalling information without questioning its source or context. Instead, critical thinking invites active engagement with content, encouraging learners to interpret, analyze, and apply information to real-world situations.

One key benefit of critical thinking is its role in enhancing problem-solving capabilities. By breaking down information into manageable parts, individuals can identify patterns, understand relationships, and evaluate the significance of various elements. For example, when presented with conflicting data, a critical thinker needs to choose more than one source but assesses the validity of each, weighing their reliability and relevance. This process enables them to make informed decisions based on evidence rather than assumptions or incomplete understanding.

Key Aspects of Critical Thinking:

Analyzing Information: Breaking complex data into smaller components to uncover relationships and significance.

Evaluating Evidence: Examining the credibility, reliability, and validity of information or sources.

Problem-Solving: Developing logical solutions by connecting ideas in meaningful ways.

Creative Thinking: Exploring alternative approaches and innovative strategies for addressing challenges.

A practical example can be observed in a student researching climate change. Instead of merely compiling a list of statistics, they might evaluate the credibility of their sources, critically examine varying opinions, and construct an argument supported by evidence.

For instance, they could compare data from scientific journals with reports from advocacy organizations, discerning the reliability of each and how it shapes public understanding. This analytical approach fosters deeper comprehension and cultivates skills to navigate complex academic, professional, and personal issues.

Critical thinking prepares individuals to handle nuanced, multifaceted challenges confidently and clearly by emphasizing active interpretation and evaluation. It shifts the focus from merely knowing facts to understanding their implications, ultimately equipping learners with the tools to approach problems thoughtfully and effectively.

Incorporating critical thinking into education profoundly impacts students' academic achievements, personal development, and future readiness. It equips them with the skills to navigate a complex, information-driven world.

Education that prioritizes critical thinking enhances learning by fostering the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information. It also builds a foundation for thoughtful, independent decision-making.

Encourages Independent Thinking

Critical thinking helps students develop the confidence and ability to question information rather than accept it at face value. This independence enables them to assess the credibility of sources, challenge assumptions, and draw conclusions. When students engage critically, they move beyond passive knowledge absorption and become active participants in their learning journey.

For instance, a student reading about historical events might examine how different authors present the same occurrence. They comprehensively understand the topic by comparing narratives, identifying biases, and analyzing motivations. This process deepens their grasp of history and sharpens their ability to scrutinize other information they encounter.

A 2018 study by the Education Testing Service revealed that only 39% of college graduates demonstrate proficiency in critical thinking. This finding highlights a significant gap in higher education outcomes and emphasizes the need to integrate critical thinking skills into curricula early.

Enhances Academic Performance

Critical thinking significantly improves students' ability to process and understand complex ideas. When students learn to break down concepts, identify relationships, and apply logic, their performance across subjects improves. They are better equipped to approach problems holistically, connect theories with real-world applications, and articulate well-reasoned conclusions.

Consider a history student tasked with analyzing primary sources. Rather than merely memorizing dates and events, they evaluate the context, compare differing accounts, and explore the socio-political factors influencing historical decisions. This analytical approach fosters deeper comprehension and allows them to present nuanced insights, elevating their academic work.

A science student conducting a lab experiment might hypothesize, test variables, and critically interpret results to form evidence-based conclusions. This method reinforces their understanding of scientific principles while cultivating transferable skills like problem-solving and logical reasoning.

Prepares Students for the Workplace

Critical thinking is consistently identified as one of the most sought-after skills by employers. Whether in problem-solving, collaboration, or innovation, the ability to think critically enables individuals to adapt and excel in professional environments. Workplace challenges often involve ambiguous or multifaceted issues requiring analysis, creativity, and sound judgment.

A project manager, for instance, must evaluate competing proposals, anticipate potential risks, and devise strategies that align with organizational goals. Employees with critical thinking skills are better equipped to handle these demands and contribute effectively to their teams and organizations.

According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, 80% of employers rank critical thinking as a top priority when evaluating job candidates. This highlights the increasing value of these skills in an evolving job market where adaptability and innovation are paramount.

Promotes Lifelong Learning

Critical thinkers are naturally curious and continually seek to learn and adapt. This mindset extends beyond the classroom, encouraging a lifetime of exploration and self-improvement. By questioning established norms, seeking diverse perspectives, and embracing change, lifelong learners remain resilient in a rapidly evolving world.

For example, a graduate who develops critical thinking skills during their education may approach career transitions or technological advancements with a problem-solving mindset. Instead of fearing change, they analyze opportunities, assess risks, and pursue informed decisions. This adaptability enhances personal growth and fosters innovation and leadership in their professional lives.

In a real-life example, a software engineer facing the emergence of new programming languages might critically evaluate their relevance, invest in upskilling, and apply their knowledge creatively to design solutions. This approach ensures they remain competitive and capable in their field.

Fosters Personal Empowerment

Beyond academic and professional contexts, critical thinking empowers individuals to navigate daily challenges and make well-informed choices. From understanding financial options to evaluating news reports, critical thinking provides the tools to discern fact from fiction and act responsibly.

For instance, a consumer deciding on a major purchase might research product reviews, consider expert opinions, and weigh long-term value over immediate gratification. This ability to analyze options and prioritize based on evidence leads to more confident and satisfying decisions.

Building a Foundation for Success

Students are equipped with tools that extend far beyond the classroom by emphasizing critical thinking in education. They become independent learners, capable professionals, and engaged citizens who contribute thoughtfully to their communities. Incorporating strategies like questioning, collaborative projects, and problem-solving exercises ensures these skills are taught and deeply ingrained.

Critical thinking is not just an academic practice but a transformative approach to understanding and engaging with the world. As educators, parents, and policymakers, fostering these skills prepares the next generation to face challenges with clarity, creativity, and confidence—paving the way for a more thoughtful and informed society.

Educators are pivotal in helping students develop critical thinking skills necessary for academic success and lifelong learning. These strategies go beyond traditional teaching methods, emphasizing active engagement, exploration, and collaboration. Here are some effective approaches:

Socratic Questioning

Socratic questioning remains one of the most powerful tools for empowering critical thinking in the classroom. By encouraging students to engage with open-ended questions, teachers prompt deeper exploration of ideas and a more nuanced understanding of concepts. This approach requires students to articulate their thoughts, evaluate evidence, and refine their reasoning.

A literature teacher might ask, "What motivations drive the protagonist's actions? How do these choices reflect the historical or cultural context of the time?" Such questions push students beyond comprehension, analyzing character motivations, historical influences, and societal implications.

Socratic questioning develops analytical skills by challenging students to justify their answers with evidence. This method encourages active participation and fosters a learning environment where curiosity thrives. Instead of simply absorbing information, students are guided to construct their understanding, making the learning process more meaningful.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

Problem-based learning places students at the center of real-world challenges, encouraging them to research , collaborate, and propose solutions. This hands-on knowledge bridges the theoretical and practical application gap, making learning relevant and engaging.

In a science class, students might be tasked with designing a model for sustainable energy use in their school. To complete the project, they would research renewable energy technologies, analyze environmental data, and consider economic feasibility. This process compels them to integrate information from multiple sources and think critically about trade-offs and constraints.

PBL enhances critical thinking and builds problem-solving and teamwork skills. Students learn to approach challenges methodically, breaking down complex problems into manageable parts and seeking innovative solutions.

Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning environments encourage students to collaborate, share ideas, and evaluate diverse perspectives. Group discussions, projects, and peer reviews expose students to various viewpoints, enhancing their ability to assess information and construct balanced arguments critically.

A report published in the Journal of Educational Psychology found that students in collaborative settings were 25% more likely to demonstrate critical thinking skills than those in individual learning environments. This increase is attributed to the exchange of ideas and constructive feedback inherent in group work.

In a history class, students could divide into groups to debate the reasons for a historical conflict. Each group might represent a different perspective, requiring them to research and present arguments while addressing counterarguments posed by their peers.

Collaborative learning builds communication and teamwork skills while fostering an appreciation for diverse perspectives. It also creates a supportive environment where students feel encouraged to question and refine their understanding.

Incorporating Technology

Digital tools have become invaluable in making learning more dynamic and interactive. Simulations, interactive quizzes, discussion forums, and debate platforms are examples of how technology can enhance critical thinking.

Debate platforms allow students to analyze arguments and counterarguments in real-time. For instance, during a unit on environmental policy, students could engage in an online debate, presenting data to support their positions while critiquing opposing views.

Technology allows students to engage actively with content, offering immediate feedback and fostering independent exploration. Simulation tools can replicate real-world scenarios, helping students apply their knowledge to practical problems in a risk-free environment.

When these teaching methods are implemented effectively, the impact extends beyond the classroom. For instance, at a middle school in Oregon, a curriculum emphasizing problem-based learning and collaborative projects resulted in a 20% increase in student participation. Teachers reported that students became more confident in their ability to analyze complex topics and articulate their ideas clearly.

Similarly, in a pilot program using technology to enhance critical thinking, high school students showed a marked improvement in their ability to evaluate the credibility of online information. They developed stronger analytical and decision-making skills by participating in digital discussions and interactive simulations.

Fostering critical thinking in students requires intentional teaching strategies that prioritize active participation, collaboration, and real-world problem-solving. Socratic questioning encourages thoughtful dialogue, problem-based learning bridges theory and practice, collaborative environments nurture diverse perspectives, and technology makes learning dynamic and accessible. By implementing these approaches, educators can equip students with the tools to connect to an increasingly complex world confidently and clearly. These strategies do more than teach content—they inspire a mindset of inquiry and adaptability that prepares students for lifelong success.

Despite critical thinking's many benefits, integrating it into classrooms takes time and effort. From rigid curricula to resource limitations, these hurdles can impede students' development of critical thinking skills. Recognizing these barriers and addressing them strategically is essential for fostering a learning environment that prioritizes analytical and evaluative skills. Below, I have for you the key challenges and potential solutions that are explored.

Curriculum Constraints

One of the most significant obstacles in teaching critical thinking is the dominance of standardized testing in educational systems. These assessments often prioritize rote memorization and recall over analytical skills, leaving little room for activities that foster deep thinking. Teachers may experience pressure to "teach to the test," focusing on meeting benchmarks rather than nurturing intellectual curiosity.

A typical standardized exam in mathematics may require students to solve equations using predetermined formulas. While this approach tests procedural knowledge, it rarely encourages students to explore why those formulas work or how they can be applied creatively to real-world problems.

Teachers can integrate critical thinking exercises into existing frameworks to address this issue. For instance, a math teacher could incorporate word problems that require students to analyze scenarios and determine the most appropriate solution. Similarly, discussions about character motivations or thematic elements can be added to standard lesson plans in literature classes. These small adaptations make room for critical thinking without compromising curriculum requirements.

Resource Limitations

Another challenge is the need for more tools and professional development opportunities available to many educators. Critical thinking requires innovative teaching methods and resources, such as case studies, interactive technologies, and collaborative activities. However, not all schools have the infrastructure or funding to support these initiatives.

Research from the Learning Policy Institute shows that schools investing in teacher training programs experience a notable improvement in both student engagement and teacher effectiveness. For example, when educators receive training in Socratic questioning or project-based learning, they are better equipped to facilitate discussions that promote deeper understanding.

Institutions can address this gap by prioritizing professional development. Workshops, online courses, and peer mentoring programs focused on critical thinking strategies can give teachers the tools they need to succeed. Additionally, partnerships with local organizations or businesses can offer access to resources like guest speakers, case studies, and hands-on learning opportunities.

Student Readiness

Students accustomed to traditional learning methods may find critical thinking challenging at first. This is especially true in environments where passive learning—listening to lectures and memorizing facts—has been the norm. Critical thinking requires active participation, which can feel unfamiliar and intimidating to some learners.

A student asked to evaluate the credibility of multiple sources in a research project may need to be taught how to identify bias or assess evidence. This difficulty can lead to frustration and disengagement.

The gradual introduction of critical thinking tasks can ease the transition. Teachers might begin with simple activities, such as asking students to evaluate and differentiate two concepts, before moving on to more complex tasks like debating ethical dilemmas or designing solutions to real-world problems. Consistent practice and positive reinforcement help build students' confidence and skills.

Effective assessment methods must be implemented to ensure students develop critical thinking skills. These assessments should go beyond traditional exams to evaluate how students apply their thinking meaningfully. Below are some methods that have proven effective:

Performance Tasks

Performance tasks place students in real-world scenarios, requiring them to analyze situations, make decisions, and justify reasoning. These tasks provide insight into how students apply their knowledge and problem-solving abilities.

In a business class, students could be asked to analyze market trends and develop a strategy for launching a new product. This task would involve interpreting data, considering consumer needs, and proposing actionable solutions, all of which would demonstrate critical thinking.

Reflective Journals

Reflective journals encourage students to document their thought processes, including how they approach problems, evaluate options, and make decisions. This practice enhances self-awareness and critical evaluation, providing valuable insights for students and teachers.

By reviewing journal entries, teachers can identify student reasoning patterns, pinpoint improvement areas, and tailor instruction to address specific needs.

Open-Ended Assessments

Open-ended questions allow students to explain their reasoning in detail, offering a clearer picture of their analytical abilities than multiple-choice tests. These assessments challenge students to think deeply, articulate their thoughts, and support their conclusions with evidence.

Instead of asking a science student to name the parts of a cell, an open-ended question might prompt them to explain how a malfunction in one part could affect the entire system. This approach requires students to synthesize information and demonstrate a thorough understanding of the topic.

The benefits of prioritizing critical thinking in education are evident in real-world examples. At a middle school in California, a critical thinking initiative centered around project-based learning was introduced. Over a year, teachers incorporated activities that required students to collaborate on solving real-world problems, such as designing eco-friendly community projects or analyzing historical events from multiple perspectives.

The results were striking:

Student participation increased by 30%.

Standardized test scores improved by 15%, particularly in subjects that need analytical skills, such as science and social studies.

Teachers reported heightened enthusiasm for learning, with students actively contributing to discussions and demonstrating greater confidence in their abilities.

This case illustrates how even small shifts toward critical thinking can profoundly impact student outcomes, both academically and emotionally. By equipping students with the skills to analyze, evaluate, and solve problems, educators prepare them for success in school, work, and life.

While challenges in teaching critical thinking exist, they are manageable. Educators can create environments where critical thinking thrives by addressing curriculum constraints, investing resources, and supporting students as they adapt to new learning methods. Assessing these skills through performance tasks, reflective journals, and open-ended assessments ensures that students learn and apply their knowledge meaningfully.

Real-world examples, like the success of the California middle school initiative, demonstrate the transformative power of critical thinking education. As educators, overcoming these hurdles means teaching students what to think and empowering them with the tools to think for themselves. This approach ultimately fosters a generation of thoughtful, innovative, and adaptable individuals ready to meet the challenges of an ever-changing world.

Teaching students to think critically prepares them for academic success and informed, thoughtful lives. Educators can cultivate skills that last a lifetime by incorporating questioning, collaboration, and real-world problem-solving into classrooms.

To create a world of empowered learners, let's ask one question: How can we think more critically about teaching?

1. How can parents encourage critical thinking at home? Encourage open-ended conversations, provide puzzles or challenges, and model thoughtful decision-making in daily life.

2. Are critical thinking skills teachable? Absolutely! With consistent practice and the right strategies, anyone can develop critical thinking.

3. How does critical thinking impact career success? It enables professionals to analyze problems, collaborate effectively, and innovate—skills valued in any industry.

4. What are some critical thinking exercises for young learners? Activities like sorting fact from opinion, debating age-appropriate topics, and analyzing simple scenarios help build foundational skills.

5. Why is collaboration essential for critical thinking? It introduces diverse perspectives, challenges students to reassess assumptions, and strengthens their reasoning.

By nurturing critical thinking, we unlock education's potential to create a brighter future for all learners. Let's prioritize this—one question, idea, and solution at a time.

Top 10 Self-Improvement Books for Personal Growth

5 reasons digital literacy is important for educators, digital literacy skills in the 21st century, what is digital literacy importance & benefits explained, why storytelling is a more important skill | benefits & techniques, 16 dominant emotions by clayton makepeace, why storytelling skills are essential for every student, the importance of digital literacy in education | benefits & challenges, why students need digital literacy in the 21st century: essential skills, standardized testing: key features, pros, cons, and alternatives, which countries offer free education, personalized learning: strategies, benefits & future trends, standardized testing: pros, cons, and effective alternatives, nepal education system: structure, reforms, and global insights, china education system: structure, reforms, and global comparisons, the importance of communication skills in academic success, social learning theory: 10 everyday examples you need to know, challenges and solutions in nepal's education system: insights and recommendations.

Improving Critical Thinking Skills in College Students

by Matthew Mahavongtrakul | Mar 6, 2020 | 390X

Erica M. Leung, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

“People grow best where they continuously experience an ingenious blend of support and challenge.” -Robert Kegan 1

Cognitive Development of College Students

Most students enter college with the notion that there are right and wrong answers and the road to knowledge is straightforward. 2 Students undergo significant cognitive growth during college, shifting their view of knowledge from objective duality to subjective multiplicity (i.e. there are various opinions, which are all valid). 2 By the time of their graduation, few students reach the cognitive stage of relativism (i.e. not all opinions are equally valid, so facts and context matter), which relies heavily on critical thinking skills to make judgments. 2

This may come as a surprise as instructors tend to expect students to have the same cognitive abilities and critical thinking skills as they do. Instead, college students are just learning how to reframe knowledge. With this in mind, instructors need to meet students where they are in their cognitive development and guide them through the process. A short epistemological belief survey may help in determining students’ stage of cognitive development.

Techniques for Developing Critical Thinking Skills

What is critical thinking? Can it be taught in the classroom? How is it measured? How can instructors help students navigate the road to independent critical thinking? Here are a few promising approaches to facilitate and encourage critical thinking:

- Collaborative learning wherein students learn from each other and work together using activities like discussion boards, case studies, role playing, peer teaching, and group projects. This technique exposes students to different interpretations of information and the diversity of fellow students’ experiences and knowledge. Collaborative learning allows students to discuss information, clarify ideas, and evaluate the validity of others’ ideas in a safe and positive environment. 3-5

- Higher-level thinking questions that prompt students to answer questions like whether they “agree or disagree” and “why”. Well-written questions will challenge students to interpret, analyze, and recognize assumptions before reaching a conclusion. 6 Examples of different levels of questions according to Bloom’s Taxonomy can be viewed here .

- Reflective written assignments that ask students to apply their experiences to different concepts, allowing students to play a more active role in their learning and self-growth. These reflections can encourage students to identify the relevance of the information to their own lives, question the information’s validity, and seek better sources. 6-8 A framework for reflective writing that can help guide students through the process can be found here .

- Open-book assessments that allow students to use notes, textbooks, and/or other resources. These foster intellectual engagement with the material instead of rote memorization, cramming, and anxiety before the exam. Since students are afforded more resources, instructors have an opportunity to ask higher level questions. Overall, these types of assessments simulate a more real-world environment, which promotes problem solving over recall. 9

Although there is debate on its definition, critical thinking is an important outcome of higher education and is highly valued by employers. It is therefore up to the instructor to incorporate ways to improve critical thinking in their students to prepare them for their futures.

- Kegan, R. In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1994).

- Black, S. & Allen, J. D. Part 3: College Student Development. TRL 58 , 214-228 (2017).

- Loes, C. N. & Pascarella, E. T. Collaborative Learning and Critical Thinking: Testing the Link. J. High. Educ. 88 , 726-753 (2017).

- Gokhale, A. A. Collaborative Learning Enhances Critical Thinking. J. Technol. Educ. 7 , 22-30 (1995).

- Szabo, Z. & Schwartz, J. Learning methods for teacher education: the use of online discussions to improve critical thinking. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 20 , 79-94 (2011).

- Walker, S. E. Active Learning Strategies to Promote Critical Thinking. J. Athl. Train. 38 , 263-267 (2003).

- Mintzberg, H. & Gosling, J. Educating Managers Beyond Borders. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 1 , 64-76 (2002).

- Naber, J. & Wyatt, T. H. The effect of reflective writing interventions on the critical thinking skills and dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. Educ. Today 34 , 67-72 (2014).

- Johans, B., Dinkens, A., & Moore, J. A systematic review comparing open-book and closed-book examinations: Evaluating effects on development of critical thinking skills. Nurse Educ. Pract. 27 , 89-94 (2017).

Matthew Mahavongtrakul edited this post on March 6th, 2020.

Recent Posts

- Highlights from UCI Teach Day 2024

- Introducing UCI Spark

- Dean’s Honorees Announced for Celebration of Teaching

- Join Us for UCI Teach Day 2024

- Inclusive Teaching and Beyond: The Need for Institutional Change

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: College Level Critical Thinking, Reading and Decision Making

Jeremy Boettinger; openstax.org/books/college-success; and Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Words of Wisdom: Thinking Critically and Creatively

Critical and creative thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. They are some of the most important skills I have ever developed. I use them everyday and continue to work to improve them both.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze a myriad of issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information? It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners, and researchers. Developing my critical thinking skills over a twenty year period as a student in higher education enabled me to complete a quantitative dissertation, including analyzing research and completing statistical analysis, and earning my Ph.D. in 2014.

While critical thinking analyzes information and roots out the true nature and facets of problems, it is creative thinking that drives progress forward when it comes to solving these problems.

Exceptional creative thinkers are people that invent new solutions to existing problems that do not rely on past or current solutions. They are the ones who invent solution C when everyone else is still arguing between A and B. Creative thinking skills involve using strategies to clear the mind so that our thoughts and ideas can transcend the current limitations of a problem and allow us to see beyond barriers that prevent new solutions from being found.

Brainstorming is the simplest example of intentional creative thinking that most people have tried at least once. With the quick generation of many ideas at once we can block-out our brain’s natural tendency to limit our solution-generating abilities so we can access and combine many possible solutions/thoughts and invent new ones. It is sort of like sprinting through a race’s finish line only to find there is new track on the other side and we can keep going, if we choose. As with critical thinking, higher education both demands creative thinking from us and is the perfect place to practice and develop the skill. Everything from word problems in a math class, to opinion or persuasive speeches and papers, call upon our creative thinking skills to generate new solutions and perspectives in response to our professor’s demands. Creative thinking skills ask questions such as—What if? Why not? What else is out there? Can I combine perspectives/solutions? What is something no one else has brought-up? What is being forgotten/ignored? What about ______? It is the opening of doors and options that follows problem-identification.

Consider an assignment that required you to compare two different authors on the topic of education and select and defend one as better. Now add to this scenario that your professor clearly prefers one author over the other. While critical thinking can get you as far as identifying the similarities and differences between these authors and evaluating their merits, it is creative thinking that you must use if you wish to challenge your professor’s opinion and invent new perspectives on the authors that have not previously been considered.

So, what can we do to develop our critical and creative thinking skills? Although many students may dislike it, group work is an excellent way to develop our thinking skills. Many times I have

heard from students their disdain for working in groups based on scheduling, varied levels of commitment to the group or project, and personality conflicts too, of course. True—it’s not always easy, but that is why it is so effective. When we work collaboratively on a project or problem we bring many brains to bear on a subject. These different brains will naturally develop varied ways of solving or explaining problems and examining information. To the observant individual we see that this places us in a constant state of back and forth critical/creative thinking modes.

For example, in group work we are simultaneously analyzing information and generating solutions on our own, while challenging other’s analyses/ideas and responding to challenges to our own analyses/ideas. This is part of why students tend to avoid group work—it challenges us as thinkers and forces us to analyze others while defending ourselves, which is not something we are used to or comfortable with as most of our educational experiences involve solo work. Your professors know this—that’s why we assign it—to help you grow as students, learners, and thinkers!

Performance vs. Learning Goals

As you have discovered in this chapter, much of our ability to learn is governed by our motivations and goals. What has not yet been covered in detail has been how sometimes hidden goals or mindsets can impact the learning process. In truth, we all have goals that we might not be fully aware of, or if we are aware of them, we might not understand how they help or restrict our ability to learn. An illustration of this can be seen in a comparison of a student that has performance -based goals with a student that has learning -based goals.

If you are a student with strict performance goals, your primary psychological concern might be to appear intelligent to others. At first, this might not seem to be a bad thing for college, but it can truly limit your ability to move forward in your own learning. Instead, you would tend to play it safe without even realizing it. For example, a student who is strictly performance-goal-oriented will often only says things in a classroom discussion when they think it will make them look knowledgeable to the instructor or their classmates. For example, a performance-oriented student might ask a question that she knows is beyond the topic being covered (e.g., asking about the economics of Japanese whaling while discussing the book Moby Dick in an American literature course). Rarely will they ask a question in class because they actually do not understand a concept. Instead they will ask questions that make them look intelligent to others or in an effort to “stump the teacher.” When they do finally ask an honest question, it may be because they are more afraid that their lack of understanding will result in a poor performance on an exam rather than simply wanting to learn.

If you are a student who is driven by learning goals, your interactions in classroom discussions are usually quite different. You see the opportunity to share ideas and ask questions as a way to gain knowledge quickly. In a classroom discussion you can ask for clarification immediately if you don’t quite understand what is being discussed. If you are a person guided by learning goals, you are less worried about what others think since you are there to learn and you see that as the most important goal.

Another example where the difference between the two mindsets is clear can be found in assignments and other coursework. If you are a student who is more concerned about performance, you may avoid work that is challenging. You will take the “easy A” route by relying on what you already know. You will not step out of your comfort zone because your psychological goals are based on approval of your performance instead of being motivated by learning.

This is very different from a student with a learning-based psychology. If you are a student who is motivated by learning goals, you may actively seek challenging assignments, and you will put a great deal of effort into using the assignment to expand on what you already know. While getting a good grade is important to you, what is even more important is the learning itself.

If you find that you sometimes lean toward performance-based goals, do not feel discouraged. Many of the best students tend to initially focus on performance until they begin to see the ways it can restrict their learning. The key to switching to learning-based goals is often simply a matter of first recognizing the difference and seeing how making a change can positively impact your own learning.

What follows in this section is a more in-depth look at the difference between performance- and learning-based goals. This is followed by an exercise that will give you the opportunity to identify, analyze, and determine a positive course of action in a situation where you believe you could improve in this area.

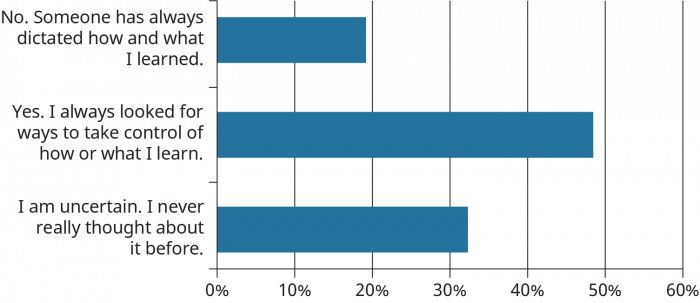

What Students Say

- No. Someone has always dictated how and what I learned.

- Yes. I always look for ways to take control of what and how I learned.

- I am uncertain. I never thought about it before.

- No. I have never heard of learning styles.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles and know my own.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles, but I don’t think they’re accurate or relate to me.

- Perseverance

- Understanding how I learn

- Good teachers and support

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

In the past, did you feel like you had control over your own learning?

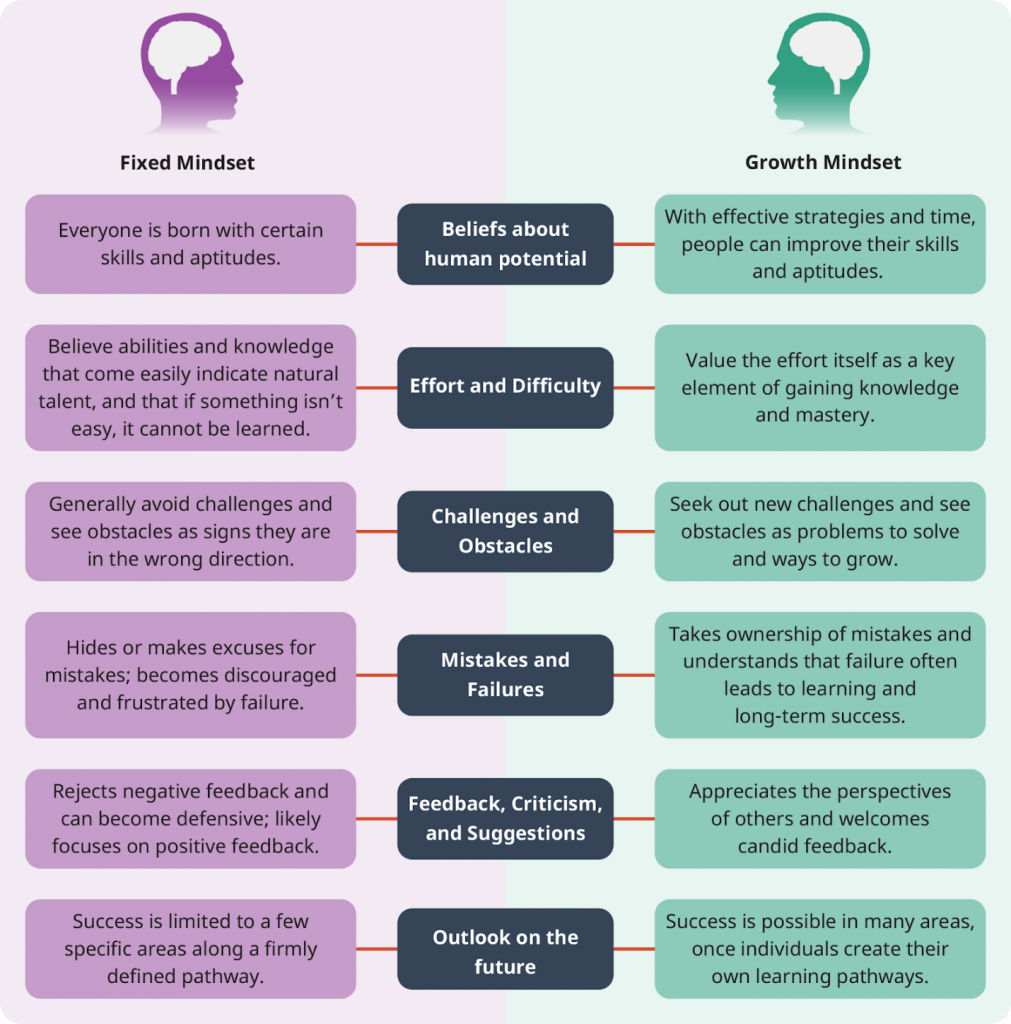

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

The research-based model of these two mindsets and their influence on learning was presented in 1988 by Carol Dweck. 7 In Dr. Dweck’s work, she determined that a student’s perception about their own learning accompanied by a broader goal of learning had a significant influence on their ability to overcome challenges and grow in knowledge and ability. This has become known as the Fixed vs. Growth Mindset model. In this model, the performance -goal-oriented student is represented by the fixed mindset, while the learning -goal-oriented student is represented by the growth mindset.

In the following graphic, based on Dr. Dweck’s research, you can see how many of the components associated with learning are impacted by these two mindsets.

The Growth Mindset and Lessons About Failing

Something you may have noticed is that a growth mindset would tend to give a learner grit and persistence. If you had learning as your major goal, you would normally keep trying to attain that goal even if it took you multiple attempts. Not only that, but if you learned a little bit more with each try you would see each attempt as a success, even if you had not achieved complete mastery of whatever it was you were working to learn.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that Dr. Dweck found that those people who believed their abilities could change through learning (growth vs. a fixed mindset) readily accepted learning challenges and persisted despite early failures.

Improving Your Ability to Learn

As strange as it may seem, research into fixed vs. growth mindsets has shown that if you believe you can learn something new, you greatly improve your ability to learn. At first, this may seem like the sort of feel-good advice we often encounter in social media posts or quotes that are intended to inspire or motivate us (e.g., believe in yourself! ), but in looking at the differences outlined between a fixed and a growth mindset, you can see how each part of the growth mindset path would increase your probability of success when it came to learning.

Very few people have a strict fixed or growth mindset all of the time. Often we tend to lean one way or another in certain situations. For example, a person trying to improve their ability in a sport they enjoy may exhibit all of the growth mindset traits and characteristics, but they find themselves blocked in a fixed mindset when they try to learn something in another area like computer programming or arithmetic.

In this exercise, do a little self-analysis and think of some areas where you may find yourself hindered by a fixed mindset. Using the outline presented below, in the far right column, write down how you can change your own behavior for each of the parts of the learning process. What will you do to move from a fixed to a growth mindset? For example, say you were trying to learn to play a musical instrument. In the Challenges row, you might pursue a growth path by trying to play increasingly more difficult songs rather than sticking to the easy ones you have already mastered. In the Criticism row, you might take someone’s comment about a weakness in timing as a motivation for you to practice with a metronome. For Success of others you could take inspiration from a famous musician that is considered a master and study their techniques.

Whatever it is that you decide you want to use for your analysis, apply each of the Growth characteristics to determine a course of action to improve.

Applying What You Know about Learning Another useful part of being an informed learner is recognizing that as a college student you will have many choices when it comes to learning. Looking back at the Uses and Gratification model, you’ll discover that your motivations as well as your choices in how you interact with learning activities can make a significant difference in not only what you learn, but how you learn. By being aware of a few learning theories, students can take initiative and tailor their own learning so that it best benefits them and meets their main needs.

Student Profile

“My seating choice significantly affects my learning. Sitting at a desk where the professor’s voice can be heard clearly helps me better understand the subject; and ensuring I have a clear view helps me take notes. Therefore, sitting in the front of the classroom should be a “go to” strategy while attending college. It will keep you focused and attentive throughout the lecture. Also, sitting towards the front of the classroom limits the tendency to be on check my phone.” —Luis Angel Ochoa, Westchester Community College

Making Decisions about Your Own Learning

As a learner, the kinds of materials, study activities, and assignments that work best for you will derive from your own experiences and needs (needs that are both short-term as well as those that fulfill long-term goals). In order to make your learning better suited to meet these needs, you can use the knowledge you have gained about UGT and other learning theories to make decisions concerning your own learning. These decisions can include personal choices in learning materials, how and when you study, and most importantly, taking ownership of your learning activities as an active participant and decision maker. In fact, one of the main principles emphasized in this chapter is that students not only benefit from being involved in planning their instruction, but learners also gain by continually evaluating the actual success of that instruction. In other words: Does this work for me? Am I learning what I need to by doing it this way?

While it may not always be possible to control every component of your learning over an entire degree program, you can take every opportunity to influence learning activities so they work to your best advantage. What follows are several examples of how this can be done by making decisions about your learning activities based on what you have already learned in this chapter.

Make Mistakes Safe

Create an environment for yourself where mistakes are safe and mistakes are expected as just another part of learning. This practice ties back to the principles you learned in the section on grit and persistence. The key is to allow yourself the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them before they become a part of your grades. You can do this by creating your own learning activities that you design to do just that. An example of this might be taking practice quizzes on your own, outside of the more formal course activities. The quizzes could be something you find in your textbook, something you find online, or something that you develop with a partner. In the latter case you would arrange with a classmate for each of you to produce a quiz and then exchange them. That particular exercise would serve double learning duty, since to create a good quiz you would need to learn the main concepts of the subject, and answering the questions on your partner’s quiz might help you identify areas where you need more knowledge.

The main idea with this sort of practice is that you are creating a safe environment where you can make mistakes and learn from them before those mistakes can negatively impact your success in the course. Better to make mistakes on a practice run than on any kind of assignment or exam that can heavily influence your final grade in a course.

Make Everything Problem Centered

When working through a learning activity, the practical act of problem-solving is a good strategy. Problem-solving, as an approach, can give a learning activity more meaning and motivation for you, as a learner. Whenever possible it is to your advantage to turn an assignment or learning task into a problem you are trying to solve or something you are trying to accomplish.

In essence, you do this by deciding on some purpose for the assignment (other than just completing the assignment itself). An example of this would be taking the classic college term paper and writing it in a way that solves a problem you are already interested in.

Typically, many students treat a term paper as a collection of requirements that must be fulfilled—the paper must be on a certain topic; it should include an introduction section, a body, a closing, and a bibliography; it should be so many pages long, etc. With this approach, the student is simply completing a checklist of attributes and components dictated by the instructor, but other than that, there is no reason for the paper to exist.

Instead, writing it to solve a problem gives the paper purpose and meaning. For example, if you were to write a paper with the purpose of informing the reader about a topic they knew little about, that purpose would influence not only how you wrote the paper but would also help you make decisions on what information to include. It would also influence how you would structure information in the paper so that the reader might best learn what you were teaching them. Another example would be to write a paper to persuade the reader about a certain opinion or way of looking at things. In other words, your paper now has a purpose rather than just reporting facts on the subject. Obviously, you would still meet the format requirements of the paper, such as number of pages and inclusion of a bibliography, but now you do that in a way that helps to solve your problem.

Make It Occupation Related

Much like making assignments problem centered, you will also do well when your learning activities have meaning for your profession or major area of study. This can take the form of simply understanding how the things you are learning are important to your occupation, or it can include the decision to do assignments in a way that can be directly applied to your career. If an exercise seems pointless and possibly unrelated to your long-term goals, you will be much less motivated by the learning activity.

An example of understanding how a specific school topic impacts your occupation future would be that of a nursing student in an algebra course. At first, algebra might seem unrelated to the field of nursing, but if the nursing student recognizes that drug dosage calculations are critical to patient safety and that algebra can help them in that area, there is a much stronger motivation to learn the subject.

In the case of making a decision to apply assignments directly to your field, you can look for ways to use learning activities to build upon other areas or emulate tasks that would be required in your profession. Examples of this might be a communication student giving a presentation in a speech course on how the Internet has changed corporate advertising strategies, or an accounting student doing statistics research for an environmental studies course. Whenever possible, it is even better to use assignments to produce things that are much like what you will be doing in your chosen career. An example of this would be a graphic design student taking the opportunity to create an infographic or other supporting visual elements as a part of an assignment for another course. In cases where this is possible, it is always best to discuss your ideas with your instructor to make certain what you intend will still meet the requirements of the assignment.

Managing Your Time

One of the most common traits of college students is the constraint on their time. As adults, we do not always have the luxury of attending school without other demands on our time. Because of this, we must become efficient with our use of time, and it is important that we maximize our learning activities to be most effective. In fact, time management is so important that there is an entire chapter in this text dedicated to it. When you can, refer to that chapter to learn more about time management concepts and techniques that can be very useful.

Instructors as Learning Partners

In K-12 education, the instructor often has the dual role of both teacher and authority figure for students. Children come to expect their teachers to tell them what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. College learners, on the other hand, seem to work better when they begin to think of their instructors as respected experts that are partners in their education. The change in the relationship for you as a learner accomplishes several things: it gives you ownership and decision-making ability in your own learning, and it enables you to personalize your learning experience to best fit your own needs. For the instructor, it gives them the opportunity to help you meet your own needs and expectations in a rich experience, rather than focusing all of their time on trying to get information to you.

The way to develop learning partnerships is through direct communication with your instructors. If there is something you do not understand or need to know more about, go directly to them. When you have ideas about how you can personalize assignments or explore areas of the subject that interest you or better fit your needs, ask them about it. Ask your instructors for guidance and recommendations, and above all, demonstrate to them that you are taking a direct interest in your own learning. Most instructors are thrilled when they encounter students that want to take ownership of their own learning, and they will gladly become a resourceful guide for you.

Application

Applying What You Know about Learning to What You Are Doing: In this activity, you will work with an upcoming assignment from one of your courses—preferably something you might be dreading or are at least less than enthusiastic about working on. You will see if there is anything you can apply to the assignment from what you know about learning that might make it more interesting.

In the table below are several attributes that college students generally prefer in their learning activities, listed in the far left column. As you think about your assignment, consider whether or not it already possesses the attribute. If it does, go on to the next row. If it does not, see if there is some way you can approach the assignment so that it does follow preferred learning attributes; write that down in the last column, to the far right.

The Hidden Curriculum

The hidden curriculum is a phrase used to cover a wide variety of circumstances at school that can influence learning and affect your experience. Sometimes called the invisible curriculum, it varies by institution and can be thought of as a set of unwritten rules or expectations.

Situation: According to your syllabus, your history professor is lecturing on the chapter that covers the stock market crash of 1929 on Tuesday of next week.

Sounds pretty straightforward and common. Your professor lectures on a topic and you will be there to hear it. However, there are some unwritten rules, or hidden curriculum, that are not likely to be communicated. Can you guess what they may be?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing before attending class?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing in class?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing after class?

- What is an unwritten rule if you are not able to attend that class?

Some of your answers could have included the following:

The expectations before, during, and after class, as well as what you should do if you miss class, are often unspoken because many professors assume you already know and do these things or because they feel you should figure them out on your own. Nonetheless, some students struggle at first because they don’t know about these habits, behaviors, and strategies. But once they learn them, they are able to meet them with ease.

While the previous example may seem obvious once they’ve been pointed out, most instances of the invisible curriculum are complex and require a bit of critical thinking to uncover. What follows are some common but often overlooked examples of this invisible curriculum.

One example of a hidden curriculum could be found in the beliefs of your professor. Some professors may refuse to reveal their personal beliefs to avoid your writing toward their bias rather than presenting a cogent argument of your own. Other professors may be outspoken about their beliefs to force you to consider and possibly defend your own position. As a result, you may be influenced by those opinions which can then influence your learning, but not as an official part of your study.