- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

Key Studies: Darley and Latane – Bystanderism (1968)

Travis Dixon October 5, 2016 Human Relationships

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Darley and Latane hypothesized two factors that may influence bystanderism:

- Diffusion of responsibility

- Social influence

- Diffusion of Responsibility

“Someone else will help.” This is one thought that might be a result of diffusion of responsibility. To diffuse means to spread something widely, so if there are more people around the responsibility of helping is spread amongst those people so individuals feels less direct responsibility for helping. So the more people there are around to help, the less likely any will help.

- Social Influence

Humans are naturally social creatures and we’re heavily influenced by the actions of others. In situations of uncertainty, we tend to look to others for information on how to behave. Many emergency situations begin ambiguously, i.e. it is not clearly apparent that it is an emergency so we may look to others for cues. In situations where someone requires help, if other around are not helping then we may not help either.

There are two types of social influence that have been termed by social psychologists normative and informational social influence. You can read more about those here .

Supporting Studies

Smokey Room

In this experiment participants sat in a waiting room and filled out a questionnaire on life as a student. After completing two pages of the questionnaire, the room slowly filled with smoke that was puffed through an air vent. By the time the participant would have finished filling out the survey, visibility was impaired due to the smoke in the room. The results were:

- Participants alone reported the smoke 75% of the time.

- Participants in groups of 3 reported the smoke 38% of the time.

- Participants with two passive confederates reported the smoke 10% of the time.

Researcher Collapsing

In this experiment participants were again filling out a questionnaire and then as the female researcher left the room they heard a crash, the sound of a body falling and the moaning of someone in pain. The results were similar to those above.

- Alone = 70% of people helped

- Groups of 3 = 40% helped

- One passive confederate = 7% helped

Participant Collapsing

In this experiment individual participants were put in soundproof rooms with headphones and microphones. They were lead to believe that the researchers were researching about personal problems of students and that they were alone with one other student or with four other students taking part in the experiment at the same time. They were in individual rooms, so they couldn’t see the other students but could hear them through their headsets. There were actually no other participants, however, they were just tape recordings. The participants heard the recordings of the other students, the first of which said they suffered from seizures sometimes. The real participant spoke last and as they spoke, the first student was heard again and started complaining and it appeared as if they were having a seizure. They then choked and went silent.

- 85% by 2 minutes, 100% by 6 minutes

- 31% by 2 minutes, 62% by six minutes.

You can download the original article here .

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

AP® Psychology

Who were latane and darley ap® psychology bystander effect review.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

Introduction to Who were Latane and Darley

If you witnessed an emergency, you would certainly help those in need, right? Even if you didn’t directly address the problem, if someone were in desperate need of help, you would definitely call the police or an ambulance at the very least, correct? Well, social psychology doesn’t think so. Based on Latane and Darley’s experiments on the bystander effect, your likelihood of helping a person in an emergency is highly dependent on the number of people around you at that moment. The bystander effect is an important social behavior from which we can learn a lot for periods of crisis, and it helps us understand human behavior for groups of people. Therefore, it is important to understand the bystander effect, its causes and possible counteractions for the Advanced Placement (AP) Psychology exam.

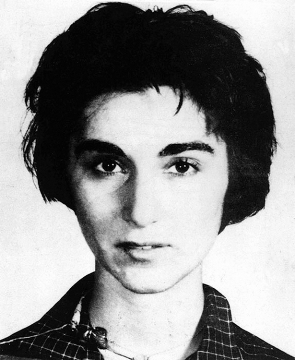

Would You Help Kitty Genovese?

New York, March 13, 1964. A woman named Catherine Susan Genovese, commonly known as Kitty Genovese, is stabbed, robbed, sexually assaulted and murdered on the street by a man named Winston Moseley. The tragedy lasted for approximately thirty minutes, during which Kitty Genovese screamed for help. The lights on the nearby apartments went on and off, neighbors heard her screaming, watched from the windows and not one of the thirty-eight witnesses called the police.

If this were a scene from a thriller book, it would sound non-realistic. The editor of the book would probably look straight at the author and protest, “You can’t put a bunch of witnesses on a thirty-minute crime and have none of them lift a finger to help! No reader would believe this!”

This is why the murder of Kitty Genovese shocked the population in 1964. We like to think we are mostly good, ethical and altruistic individuals who would never refuse to help someone in an emergency. At the time, professors and preachers tried to explain this apparently horrifying indifference and lack of intervention with reasons such as “moral decay,” “alienation” and “dehumanization produced by the urban environment.” Social psychology researchers Bibb Latane and John Darley , however, had another hypothesis.

Their hypothesis was that when we are in the presence of other people, we are less likely to intervene in an emergency. Why? What happens? What’s so different between being alone and being in a group when a problem occurs? This is what Latane and Darley explored in their experiments on bystander effect, a critical discovery in the field of social psychology .

The Experiments

In 1968, Latane and Darley created a situation similar to that of Kitty Genovese’s (but without violence)to understand what social forces were acting on the day of the crime.

In the first experiment, Latane and Darley recruited college students to participate in what seemed to be an innocent talk with other college students. Each participant was given headphones and a microphone and stayed alone in a room, talking to other students through the intercom. According to the researchers, this was done to protect everyone’s anonymity. The theme of the conversation was college life problems, worries and the like.

Next, Latane and Darley divided the participants into three groups:

- The first group thought they were talking one on one with the other person

- The second group thought they were talking with two other people

- The third group thought they were talking in a group of five people

In a certain point of the conversation, a person in the intercom started acting as if he was having a seizure and asked for help. Latane and Darley wanted to investigate the difference of behavior between each group, according to the number of witnesses. These were the results:

- When participants thought they were the only ones who could help, 85% of them left the room and asked for assistance

- When participants thought there were other two bystanders with them, that number dropped to 64%

- In the situation with four bystanders, only 31% of participants searched for help

“Well, okay,” you might say, “Maybe the number of people around you influences the likelihood of giving assistance, but if it were the participants’ own lives that were at risk, I’m sure everybody would do something regardless of the number of bystanders.”

Latane and Darley thought about that too and developed a second experiment to investigate this. How do you think that one went down?

For the second experiment, Latane and Darley once again recruited college students, this time to “fill out a questionnaire.” They divided the participants into two groups:

- Participants filling out the questionnaire alone in a room

- Participants filling out the questionnaire with many confederates in the room who were also filling out the questionnaire

A few minutes after the participants start the task, a black smoke starts to creep out from the room’s air conditioner. It gets thicker and thicker until the room is filled with smoke. However, in the second group, the confederates were instructed to ignore the smoke, and so no one seems to be bothered about it. What do you think happened?

- Of the participants who were alone, 75% quickly left the room and reported the smoke to the researchers

- Of those who were in the room with the unshaken confederates, only 10% left the room and searched for help, after twice the time of the participants who were alone

This is a surprising result that confirms the first study’s findings: the greater the number of bystanders, the less likely we are to act. Even if we ourselves could be in danger, being surrounded by people who do nothing makes us more likely also to do nothing. This opposes the intuitive idea that the more people there are in an emergency situation, the more likely it is that someone would call for help. As Latane and Darley have shown in their studies, it is quite the contrary.

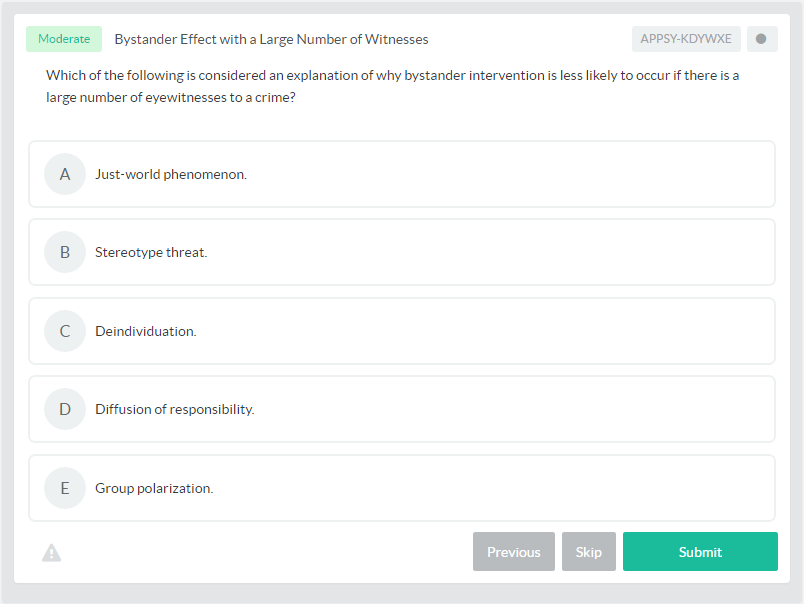

Why the Bystander Effect Happens

As we have seen earlier, the bystander effect states that the likelihood of intervention is inversely related to the number of bystanders . In other words, the more witnesses there are, the less likely each one of them is to intervene in a problematic situation. But why does this happen? What can explain this?

The main reason proposed by Latane and Darley is diffused responsibility. When you are in a large group and something needs to be done, you feel less responsible for the task. There are so many people around; someone else is surely taking charge of the situation, so why should you step up? The sense of responsibility is diffused in the group, and the result is that, very frequently, no one does anything.

This is what happened in the Kitty Genovese situation. The thirty-eight neighbors witnessed the crime and saw each other through the windows. “Of course someone will call the police,” each one of them thought, “a woman is being murdered right on the street!” Unfortunately, diffused responsibility led to none of them taking action.

Another reason for the bystander effect pointed out by Latane and Darley is pluralistic ignorance . Pluralistic ignorance is what happens when you observe a situation and at first think that, for example, it is dangerous. However, people around act as if it isn’t a problem and don’t look concerned. Then, you also assume that it’s really not a big deal and that the right thing to do is just to keep doing what you’re doing and not intervene.

In the Kitty Genovese situation, the neighbors looked around to check how others were reacting, and since no one was getting desperate and fighting to help her (because of the diffused responsibility effect), they continued with their everyday lives despite her persistent cries for help.

How the Bystander Effect Happens

According to Latane and Darley, bystanders go through a 5-step cognitive and behavioral process in emergency situations:

- Notice that something is happening – many things influence our ability to notice a situation, for example, being in a hurry or being in a group in which no one notices the event.

- Interpret the situation as an emergency – this is where the pluralistic ignorance becomes a problem, especially in ambiguous situations when people aren’t quite sure of what is happening and therefore don’t act in an urgent manner.

- Assume a degree of responsibility – this is affected by the diffused responsibility phenomenon and also by other elements such as whether we see the victim as someone deserving of help, whether we see ourselves as someone capable of helping and the relationship between the victim and ourselves.

- Choose a form of assistance – this can be a direct intervention helping the victim or a detour intervention like calling the police.

- Take action – performing the assistance chosen.

Other Variables that Influence Our Likelihood to Help

Latane and Darley’s crucial studies were further investigated by other social psychologists who continued to develop the knowledge on what makes us more likely to help others and show altruistic behavior. Some of the other variables are:

- Similarity: we are more likely to help those who are in some way similar to ourselves. This can be regarding gender, ethnicity, clothes, beliefs and even the basketball team the victim happens to root for.

- Consequences: when we think there will be strong consequences for our intervention, we are less likely to act. For example, many people avoid intervening in emergency medical situations because they are afraid of giving inadequate assistance, making the situation worse and later being held responsible for it.

- Familiarity with the environment: we are more likely to intervene in situations in places we are familiar with. That can be because, for instance, we know where the emergency exits are or where to find help quickly.

How to Counter the Bystander Effect

Okay, so now you know the dangers of the bystander effect and why and how it happens. You might be wondering: “Is there anything we can do to avoid it? How can we increase the likelihood of helping other people?”

Fortunately, there are possible measures to counter the bystander effect and avoid future Kitty Genovese situations. After all, this is the main reason to study human behavior: not to think of our tendencies in a conformed and cynical way and make the same mistakes over and over again, but to reflect on how we can improve ourselves, our lives and our relationships. So here are a few tips to use this knowledge in our service:

- Recognize situations where the bystander effect may be present and be aware of them. Realize that we are all bystanders. By doing so, next time there is a problem you’ll be able to notice it, interpret it as an emergency and assume responsibility more clearly.

- Review your concepts about who deserves help. This can get tricky when people perceive the victim as someone who brought their unfortunate events upon themselves, like drug or alcohol addicts. No one is forced to offer assistance to everybody in need, but be aware of your own ideas and tendencies.

- Know how to help people in different situations. Seeing yourself as more qualified to give assistance raises the likelihood of that behavior.

- If you need help, choose a specific person to ask for it. This avoids the diffused responsibility phenomenon. Instead of saying “Someone call an ambulance,” point directly to someone and say “You, call an ambulance!”

- If someone needs help, be the one to take action. Once people see that somebody is intervening, they are more likely to start offering assistance as well.

A Free Response Question (FRQ) Example

Now that you’ve learned all about Latane and Darley’s bystander effect, try to answer the following FRQ from a past exam:

For each of the following pairs of terms, explain how the placement or location of the first influences the process indicated by the second:

– Presence of other, performance

There are many possible answers to this question, for example social facilitation, social loafing, conformity and the theme of this AP® Psychology review : the bystander effect. Whatever you choose, the important thing is to correctly describe the phenomenon of choice and connect the elements “presence of other” and “performance” in a clear way.

So what do you think about the bystander and the diffused responsibility effect? Have you ever been in a situation where you saw Latane and Darley’s principles in action? Share in the comments below!

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this AP® Psychology practice question:

Looking for more AP® Psychology practice?

Check out our other articles on AP® Psychology .

You can also find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery of AP Psychology.

Start practicing here .

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting AP® Psychology student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

IMAGES