Redi experiment (1665)

Microbe Notes

Experiments in support and against Spontaneous Generation

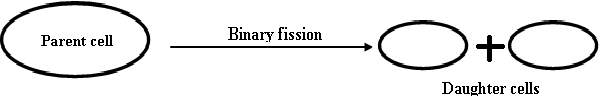

- Spontaneous generation is an obsolete theory which states that living organisms can originate from inanimate objects.

- The theory believed that dust created fleas, maggots arose from rotting meat, and bread or wheat left in a dark corner produced mice among others.

- Although the idea that living things originate from the non-living may seem ridiculous today, the theory of spontaneous generation was hotly debated for hundreds of years.

- During this time, many experiments were conducted to both prove and disprove the theory.

Table of Contents

Interesting Science Videos

Experiments in Support of Spontaneous Generation

The doctrine of spontaneous generation was coherently synthesized by Aristotle, who compiled and expanded the work of earlier natural philosophers and the various ancient explanations for the appearance of organisms, and was taken as scientific fact for two millennia.

- The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) was one of the earliest recorded scholars to articulate the theory of spontaneous generation, the notion that life can arise from nonliving matter.

- Aristotle proposed that life arose from nonliving material if the material contained pneuma (“vital heat”).

- As evidence, he noted several instances of the appearance of animals from environments previously devoid of such animals, such as the seemingly sudden appearance of fish in a new puddle of water.

John Needham

- The English naturalist John Turberville Needham was in support of the theory.

- Needham found that large numbers of organisms subsequently developed in prepared infusions of many different substances that had been exposed to intense heat in sealed tubes for 30 minutes.

- Assuming that such heat treatment must have killed any previous organisms, Needham explained the presence of the new population on the grounds of spontaneous generation.

- By this time, the proponents of the theory cited how frogs simply seem to appear along the muddy banks of the Nile River in Egypt during the annual flooding.

- Others observed that mice simply appeared among grain stored in barns with thatched roofs. When the roof leaked and the grain molded, mice appeared.

- Jan Baptista van Helmont , a seventeenth century Flemish scientist, proposed that mice could arise from rags and wheat kernels left in an open container for 3 weeks.

Experiments against Spontaneous Generation

Though challenged in the 17th and 18th centuries by the experiments of Francesco Redi and Lazzaro Spallanzani, spontaneous generation was not disproved until the work of Louis Pasteur and John Tyndall in the mid-19th century.

Francesco Redi

- The Italian physician and poet Francesco Redi was one of the first to question the spontaneous origin of living things.

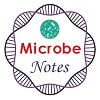

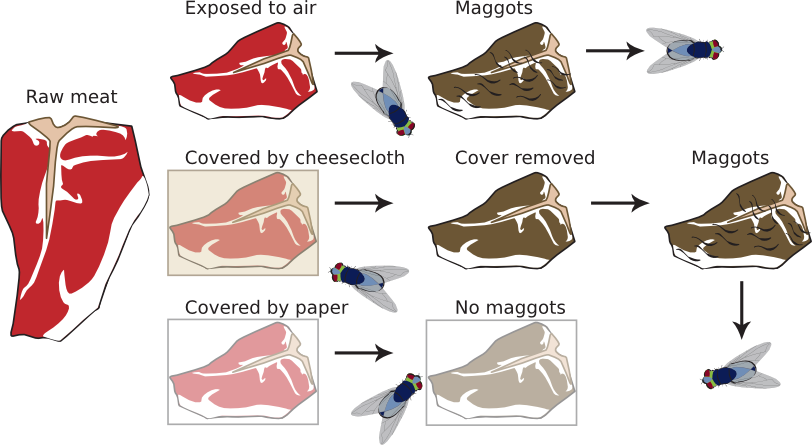

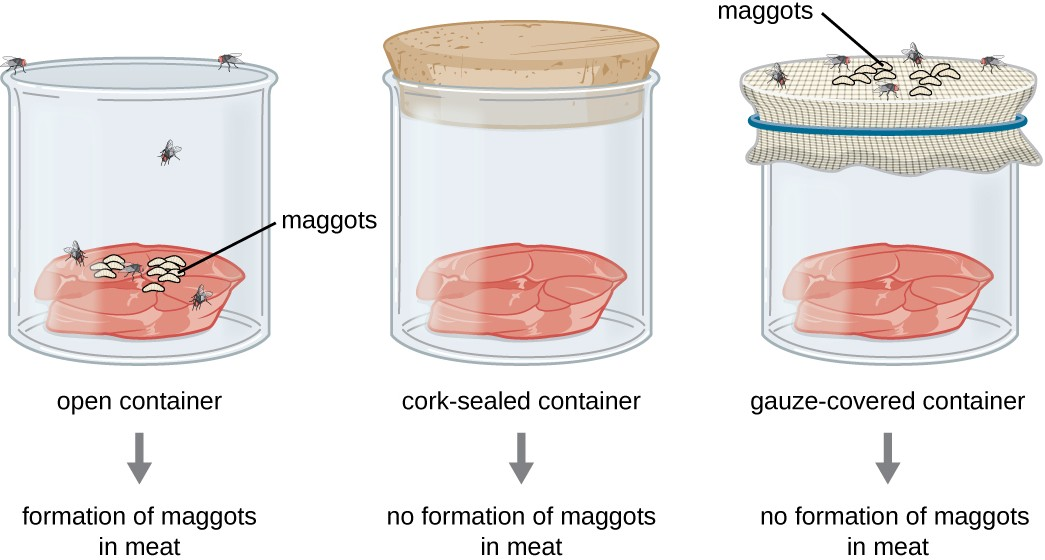

- Having observed the development of maggots and flies on decaying meat, Redi in 1668 devised a number of experiments, all pointing to the same conclusion: if flies are excluded from rotten meat, maggots do not develop. On meat exposed to air, however, eggs laid by flies develop into maggots.

- He tested the spontaneous creation of maggots by placing fresh meat in each of two different jars.

- One jar was left open; the other was covered with a cloth. Days later, the open jar contained maggots, whereas the covered jar contained no maggots.

- He did note that maggots were found on the exterior surface of the cloth that covered the jar. Redi successfully demonstrated that the maggots came from fly eggs.

Lazzaro Spallanzani

- The experiments of Needham appeared irrefutable until the Italian physiologist Lazzaro Spallanzani repeated them and obtained conflicting results.

- He published his findings around 1775, claiming that Needham had not heated his tubes long enough, nor had he sealed them in a satisfactory manner.

- Although Spallanzani’s results should have been convincing, Needham had the support of the influential French naturalist Buffon; hence, the matter of spontaneous generation remained unresolved.

Louis Pasteur

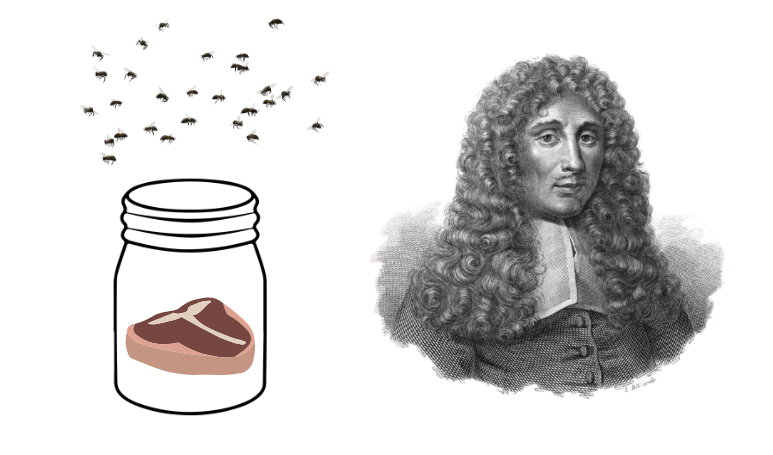

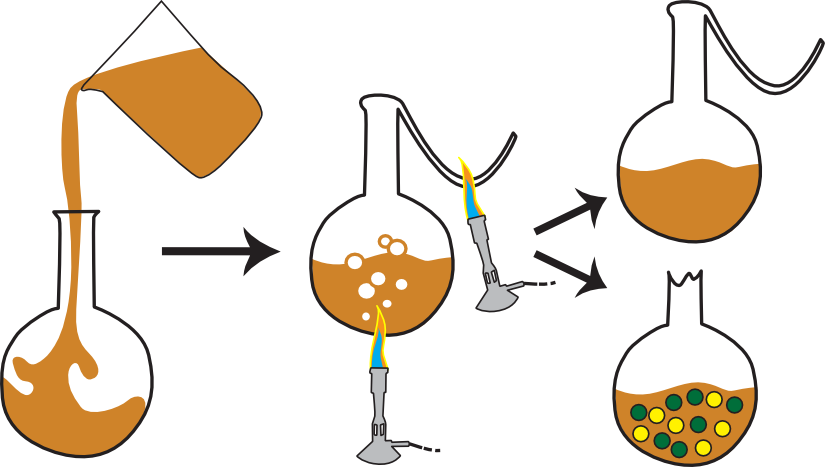

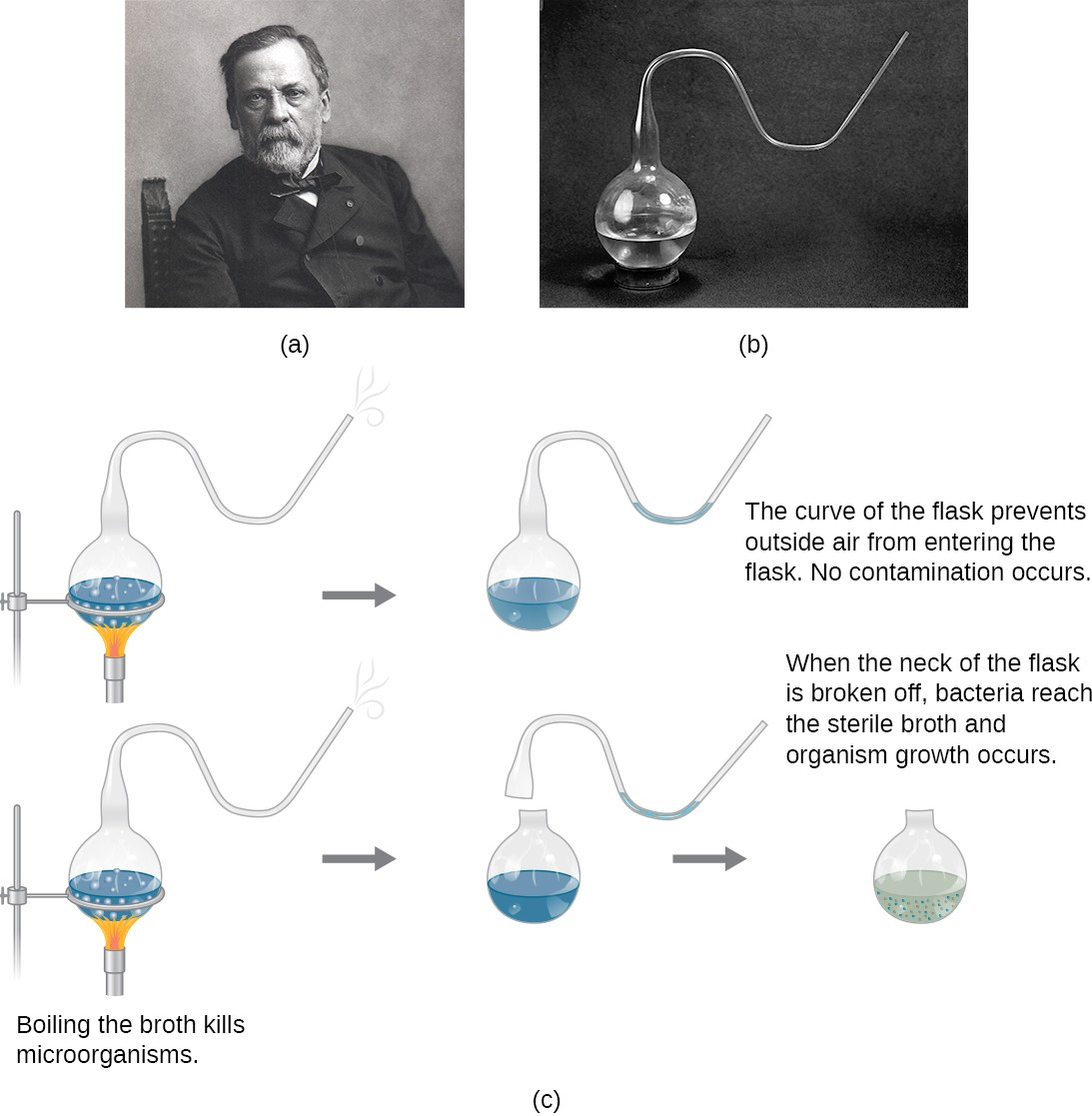

- Louis Pasteur ‘s 1859 experiment is widely seen as having settled the question of spontaneous generation.

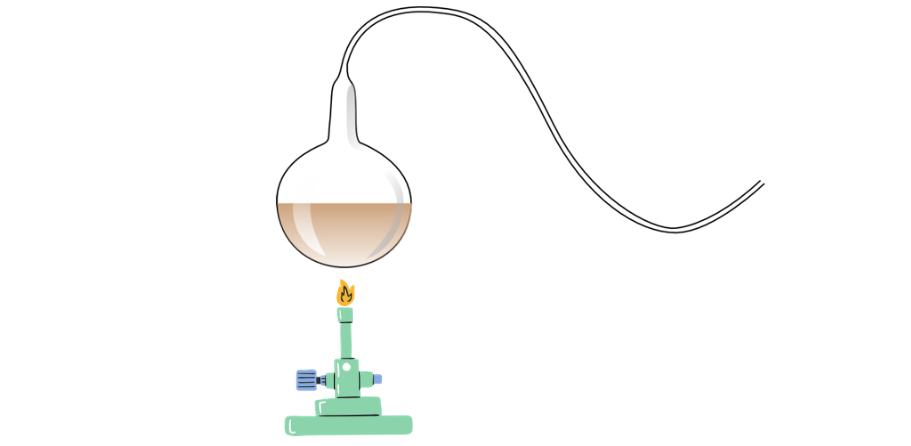

- He boiled a meat broth in a flask that had a long neck that curved downward, like that of a goose or swan.

- The idea was that the bend in the neck prevented falling particles from reaching the broth, while still allowing the free flow of air.

- The flask remained free of growth for an extended period. When the flask was turned so that particles could fall down the bends, the broth quickly became clouded.

- This work was so conclusive; that biology codified the “Law of Biogenesis,” which states that life only comes from previously existing life.

John Tyndall

- Support for Pasteur’s findings came in 1876 from the English physicist John Tyndall, who devised an apparatus to demonstrate that air had the ability to carry particulate matter.

- Because such matter in air reflects light when the air is illuminated under special conditions, Tyndall’s apparatus could be used to indicate when air was pure.

- Tyndall found that no organisms were produced when pure air was introduced into media capable of supporting the growth of microorganisms.

- It was those results, together with Pasteur’s findings, that put an end to the doctrine of spontaneous generation.

- Parija S.C. (2012). Textbook of Microbiology & Immunology.(2 ed.). India: Elsevier India.

- Sastry A.S. & Bhat S.K. (2016). Essentials of Medical Microbiology. New Delhi : Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/spontaneous-generation-definition-theory-examples.html

- https://www.britannica.com/science/biology#ref498783

- https://www.infoplease.com/science/biology/origin-life-spontaneous-generation

- https://www.allaboutscience.org/what-is-spontaneous-generation-faq.htm

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/microbiology/chapter/spontaneous-generation/

About Author

Sagar Aryal

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Food Untold

Discovering the Wonders of Science in Food

How Louis Pasteur Debunked the Spontaneous Generation Theory

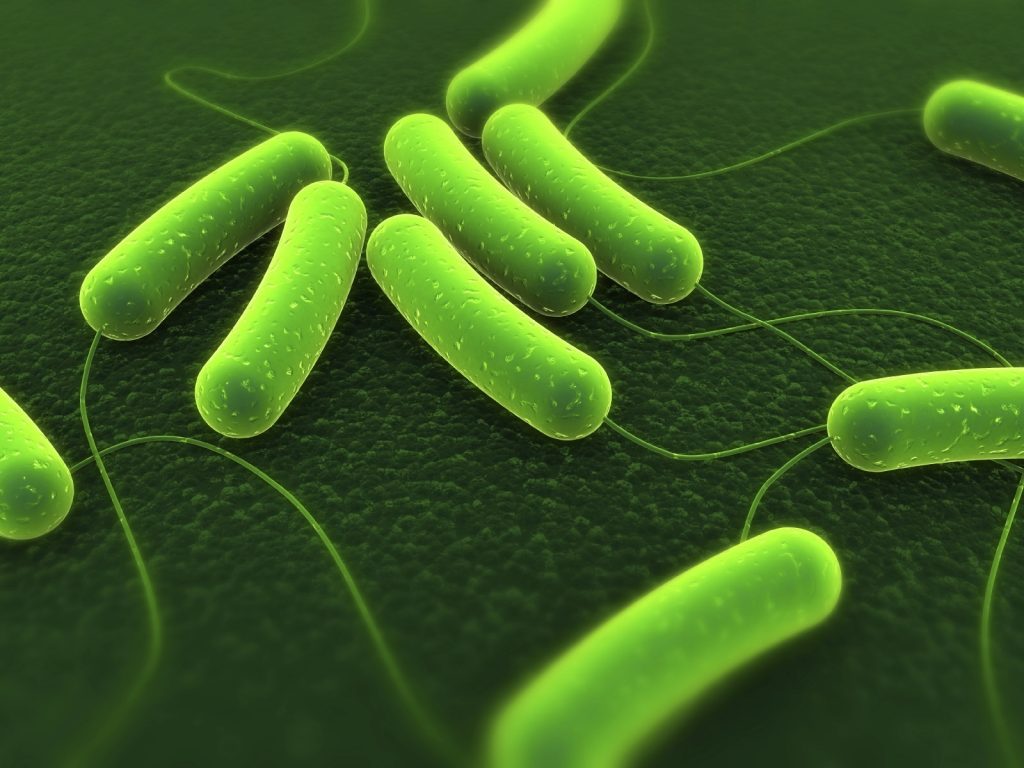

Philosopher Aristotle coined the idea of the spontaneous generation theory in 4th century BCE, 22 centuries before time of Louis Pasteur. This theory stated that living matter could arise from non-living matter spontaneously. One of the most famous examples of this theory is that maggots could appear on decaying piece of meat.

This idea went on to persist for a very long time. This is due largely to the fact that it easily explained how mold grow on bread or that flies appear on spoiled food.

But this idea did not align to many scientists, many of them tried to disprove this idea, including Louis Pasteur.

Table of Contents

Early challenges to spontaneous generation

For a millennium, Aristotle’s theory of spontaneous generation was widely believed around the world. Was this because of the lack of technology that science enjoys today? For example, microscopes were far from being invented to allow researchers to observe and study microorganisms. Hence, experiments to test theories were not really much of a thing back then.

By the 1600, scientists and scholars have started questioning the factualness of the theory. One of these individuals who challenged the theory was Italian physician Francesco Redi. He showed that maggots do not spontaneously arise from decaying meat by doing the so-called “Redi experiment” in 1668.

In this experiment, Redi set up 3 jars of various conditions. The first jar was open and let flies to enter the jar. The second jar was tightly to prevent flies from entering. And the last jar was covered with a mesh. After letting the jars sit for a short period, maggots appeared in the open jar and mesh-covered jar, but not the tightly sealed one.

Redi concluded that flies laid eggs that would hatch into maggots. This result suggested that living matters like maggots come from other living matters, and do not arise spontaneously. Although the Redi experiment demonstrated that living matters could only arise from pre-existing living matters, this was not sound enough to disprove the spontaneous generation theory.

Hence, the debate continued.

Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek contribution

Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek was a Dutch scientist known as the Father of Microbiology. He developed microscopes during the 17th century that were considered advance during that time. Leeuwenhoek made about 500 microscopes in this career. One of these could magnify objects up to 300 times. This capability was unrivaled back then. In comparison, the microscope English physicist Robert Hooke developed could only magnify up to 50 times. This magnification could only reveal basic details on minute organisms.

Leeuwenhoek’s, on the other hand had greater magnification. This allowed him to study various microorganisms in greater detail. Leeuwenhoek described bacteria, yeasts, and other microorganisms. Their shapes, movement, and behavior were documented for the first time. But his discovery of the existence of microorganisms was not solid evidence to dispel the spontaneous generation theory.

You might also like: The Bacteria That Make Limburger Cheese Smell

When his work was made public, scientist still wondered the same question. Do microorganisms come from pre-existing living things? Or they just generate spontaneously from non-living things? Yes, the scope of microbiology back then was very limited. However, Leeuwenhoek’s contribution to understanding microorganisms paved the way for another scientist to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation at once, Louis Pasteur.

Louis Pasteur’s works prior to debunking the spontaneous generation theory

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist. He lived during the 19th century. At this point, the debate on the spontaneous generation theory was at its peak. Prior to disproving the theory, he already worked on fermentation, and pasteurization.

In 1850s, Pasteur studied extensively the process of fermentation. Fermentation is a preservation method wherein sugar in food is converted into alcohol or acid. Prior to Pasteur’s research on the process, it was widely accepted that fermentation was solely a chemical process. The belief was that fermentation would occur because components in food decompose in the absence of air. Hence, microorganisms were not believed to be responsible in fermentation.

But Pasteur’s work changed this when he studied spoilage in wine and beer. In the mid-19th century, the brewing industry in France was suffering from economic losses due to spoilage of wine. The losses were massive that it hit wine exports badly. To resolve the problem, Napoleon III and the French government asked for help from Pasteur. He then presented clear evidence that undesirable or spoilage microorganisms were responsible for the off-flavor and souring in wine.

What Pasteur did was preheat the wine at between 122°F (50°C) and 140°F (140). This prevented souring and extended the shelf life of wine.

Based on his research on microorganisms, spoilage microorganisms found in wine are heat sensitive. Hence, he hypothesized that treating the wine with elevated heat high enough to destroy these microbes would effectively extend the shelf life of wine. The temperature range he used was well thought of because not only it killed unwanted microbes, but it was also not high enough to preserve the flavor of the wine. This heat treatment is now called pasteurization.

Pasteur’s Swan-Neck Flask experiment debunked the spontaneous generation

Louis Pasteur became aware of the spontaneous generation when he came to know fellow Frenchmen Felix Archimède Pouchet, a strong follower of the spontaneous generation theory. Pasteur had been very skeptical about the theory, and the French Academy of Sciences opened a competition called Alhumbert Prize to ultimately put an end to this debate. Pasteur took up the challenge and performed an experiment that would ultimately debunk the theory— the Swan-Neck flask experiment.

In this experiment, Pasteur gathered a number of long, curved S-shaped flasks that looked like swan’s neck, hence the name of the experiment. He filled each flask with an infusion or nutrient rich broth. After that, he pasteurized the flasks to destroy the harmful microorganisms that were present in the broth.

After letting the pasteurized broth in the flask to sit for some time he observed what happened. And just as he predicted, the broth did not change in appearance or appear to have been contaminated. The unique S-shape of the flask prevented contaminated to happen here. The curve neck allowed air to flow through, but not dust and any other elements that may contaminate the broth.

But if the curved long neck of the flasks were removed, or the flask were tilted that the broth got into contact with the curve neck, airborne microorganisms would have been introduced to the broth and contaminate it.

The Swan-Neck flask experiment by Pasteur ultimately debunked the spontaneous generation theory. Because of this, he was awarded the Alhumbert prize, which also carried a value of 2,500 francs. This was considered a huge sum already in 1862.

- ← What Is Vacuum Packaging In Food Preservation?

- Why Calcium Propionate Is In My Bread? →

You May Also Like

Can Salmonella Be Killed By Cooking?

Lactic Acid Fermentation: An Overview

Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast In The Food Industry

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Origin of Life: Spontaneous Generation

- Spontaneous Generation

Origin of Life

- Introduction

- Early Earth Environment

It was once believed that life could come from nonliving things, such as mice from corn, flies from bovine manure, maggots from rotting meat, and fish from the mud of previously dry lakes. Spontaneous generation is the incorrect hypothesis that nonliving things are capable of producing life. Several experiments have been conducted to disprove spontaneous generation; a few of them are covered in the sections that follow.

Redi's Experiment and Needham's Rebuttal

In 1668, Francesco Redi, an Italian scientist, designed a scientific experiment to test the spontaneous creation of maggots by placing fresh meat in each of two different jars. One jar was left open; the other was covered with a cloth. Days later, the open jar contained maggots, whereas the covered jar contained no maggots. He did note that maggots were found on the exterior surface of the cloth that covered the jar. Redi successfully demonstrated that the maggots came from fly eggs and thereby helped to disprove spontaneous generation. Or so he thought.

In England, John Needham challenged Redi's findings by conducting an experiment in which he placed a broth, or gravy, into a bottle, heated the bottle to kill anything inside, then sealed it. Days later, he reported the presence of life in the broth and announced that life had been created from nonlife. In actuality, he did not heat it long enough to kill all the microbes.

Spallanzani's Experiment

Lazzaro Spallanzani, also an Italian scientist, reviewed both Redi's and Needham's data and experimental design and concluded that perhaps Needham's heating of the bottle did not kill everything inside. He constructed his own experiment by placing broth in each of two separate bottles, boiling the broth in both bottles, then sealing one bottle and leaving the other open. Days later, the unsealed bottle was teeming with small living things that he could observe more clearly with the newly invented microscope. The sealed bottle showed no signs of life. This certainly excluded spontaneous generation as a viable theory. Except it was noted by scientists of the day that Spallanzani had deprived the closed bottle of air, and it was thought that air was necessary for spontaneous generation. So although his experiment was successful, a strong rebuttal blunted his claims.

Pasteurization originally was the process of heating foodstuffs to kill harmful microorganisms before human consumption; now ultraviolet light, steam, pressure, and other methods are available to purify foodsin the name of Pasteur.

Pasteur's Experiment

Louis Pasteur, the notable French scientist, accepted the challenge to re-create the experiment and leave the system open to air. He subsequently designed several bottles with S-curved necks that were oriented downward so gravity would prevent access by airborne foreign materials. He placed a nutrient-enriched broth in one of the goose-neck bottles, boiled the broth inside the bottle, and observed no life in the jar for one year. He then broke off the top of the bottle, exposing it more directly to the air, and noted life-forms in the broth within days. He noted that as long as dust and other airborne particles were trapped in the S-shaped neck of the bottle, no life was created until this obstacle was removed. He reasoned that the contamination came from life-forms in the air. Pasteur finally convinced the learned world that even if exposed to air, life did not arise from nonlife.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Biology © 2004 by Glen E. Moulton, Ed.D.. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books , a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

To order this book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website or call 1-800-253-6476. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble .

- Origin of Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes: Origin of Prokaryotes

Here are the facts and trivia that people are buzzing about.

- Site search

- Through the Microscope

- Why Microbes Matter

- Remember me

- Log in page

- Create new account

- Recover lost username

- Recover lost password

- Contact the Author

- Contact the Webmaster

Latest News

1-6 spontaneous generation was an attractive theory to many people, but was ultimately disproven..

( 64555 Reads)

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, students will be able to...

- Explain why people believed in the concept of spontaneous generation, the creation of life from organic matter.

- Describe the experiment by Francesco Redi disproved spontaneous generation that disproved spontaneous generation for macroorganisms.

- Explain how did John Needham's experiment re-ignited the debate about spontaneous generation for microorganisms.

- Describe the swan-neck flask experiment of Louis Pasteur and why this ended the debate about spontaneous generation.

Spontaneous generation hypothesizes that some vital force contained in or given to organic matter can create living organisms from inanimate objects. Spontaneous generation was a widely held belief throughout the middle ages and into the latter half of the 19 th century. Some people still believe in it today. The idea was attractive because it meshed nicely with the prevailing religious views of how God created the universe. There was a strong bias to legitimize the idea because this vital force was considered a strong proof of God's presence in the world. Proponents offered many recipes and experiments in proof. To create mice, mix dirty underwear and wheat grain in a bucket and leave it open outside. In 21 days or less, you would have mice. The real cause may seem obvious from a modern perspective, but to the supporters of this idea, the mice spontaneously arose from the wheat kernels.

Another often-used example was the generation of maggots from meat left in the open. Francesco Redi revealed the failing here in 1668 with a classic experiment. Redi suspected that flies landing on the meat laid eggs that eventually grew into maggots . To test this idea, he devised the experiment shown in Figure 1.11. Here he used three pieces of meat. Redi placed one piece of meat under a piece of paper. The flies could not lay eggs onto the meat, and no maggots developed. The second piece was left in the open air, resulting in maggots. In the final test, Redi overlayed the third piece of meat with cheesecloth. The flies could lay the eggs into the cheesecloth, and when he removed this, no maggots developed. However, if Redi placed the cheesecloth containing the eggs on a fresh piece of meat, maggots developed, showing it was the eggs that "caused" maggots and not spontaneous generation. Redi ended the debate about spontaneous generation for large organisms. However, spontaneous generation was so seductive a concept that even Redi believed it was possible in other circumstances.

Figure 1.11. The Redi experiment. . Using several pieces of meat, paper and cheesecloth, Francesco Redi produced compelling evidence against the theory of spontaneous generation. One of the strong points of this experiment was its simplicity, which allowed others to easily reproduce it for themselves. See the text for details of the experiment.

The concept and the debate were revived in 1745 by the experiments of John Needham. It was known at the time that heat was lethal to living organisms. Needham theorized that if he took chicken broth and heated it, all living things in it would die. After heating some broth, he let a flask cool and sit at a constant temperature. The development of a thick turbid solution of microorganisms in the flask was strong proof to Needham of the existence of spontaneous generation. Lazzaro Spallanzani later repeated the experiments of Needham, but removed air from the flask, suspecting that the air was providing a source of contamination. No growth occurred in Spallanzani's flasks, and he took this as evidence that Needham was wrong. Proponents of spontaneous generation discounted the experiment by asserting that the vital force needed air to work properly.

It was not until almost 100 years later that the great French chemist Louis Pasteur, pictured in Figure 1.12, put the debate to rest. He first showed that the air is full of microorganisms by passing air through gun cotton filters. The filter trapped tiny particles floating in the air. By dissolving the cotton with an ether/alcohol mixture, the particles were released and then settled to the bottom of the liquid. Inspection of this material revealed numerous microbes that resembled the types of bacteria often found in putrefying media. Pasteur realized that if these bacteria were present in the air, they would likely land on and contaminate any exposed material.

Figure 1.12. Louis Pasteur . The French microbiologist Louis Pasteur. Drawing by Tammi Henke

Pasteur then entered a contest sponsored by The French Academy of Sciences to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation. Similar to Spallanzani's experiments, Pasteur's experiment, pictured in Figure 1.13, used heat to kill the microbes but left the end of the flask open to the air. In a simple but brilliant modification, he heated the neck of the flask to melting and drew it out into a long S-shaped curve, preventing the dust particles and their load of microbes from ever reaching the flask. After prolonged incubation, the flasks remained free of life and ended the debate for most scientists.

Figure 1.13. The swan neck flask experiment . Pasteur filled a flask with medium, heated it to kill all life, and then drew out the neck of the flask into a long S shape. This prevented microorganisms in the air from easily entering the flask, yet allowed some air interchange. If the swan neck was broken, microbes readily entered the flask and grew

A final footnote on the topic was added when John Tyndall show ed the existence of heat-resistant spores in many materials. Boiling does not kill these spores, and their presence in chicken broth, as well as many other materials, explains the results of Needham's experiments.

While this debate may seem silly from a modern perspective, remember that the scientists of the time had little knowledge of microorganisms. Koch would not isolate microbes until 1881. The proponents of spontaneous generation were neither sloppy experimenters nor stupid. They did careful experiments and interpreted them with their own biases. Detractors of the theory of spontaneous generation were just as guilty of bias but in the opposite direction. It is somewhat surprising that Pasteur and Spallanzoni did not get growth in their cultures since the sterilization conditions they used would often not kill endospores . Luck certainly played a role. It is important to keep in mind that the discipline of science is performed by humans with all the fallibility and bias inherent in the species. Only the self-correcting nature of the practice reduces the impact of these biases on generally held theories. Spontaneous generation was a severe test of scientific experimentation because it was such a seductive and widely held belief. Yet, even spontaneous generation was overthrown when the weight of careful experimentation argued against it. Table 1.3 lists important events in the spontaneous generation debate.

Table 1.3 Events in spontaneous generation

Key takeaways.

- For many centuries many people believed in the concept of spontaneous generation, the creation of life from organic matter.

- Francesco Redi disproved spontaneous generation for large organisms by showing that maggots arose from meat only when flies laid eggs in the meat.

- Spontaneous generation for small organisms again gained favor when John Needham showed that if a broth was boiled (presumed to kill all life) and then allowed to sit in the open air, it became cloudy.

- Louis Pasteur ended the debate with his famous swan-neck flask experiment, which allowed air to contact the broth. Microbes present in the dust were not able to navigate the tortuous bends in the neck of the flask.

2.1 Spontaneous Generation

Learning objectives.

- Explain the theory of spontaneous generation and why people once accepted it as an explanation for the existence of certain types of organisms

- Explain how certain individuals (van Helmont, Redi, Needham, Spallanzani, and Pasteur) tried to prove or disprove spontaneous generation

Humans have been asking for millennia: Where does new life come from? Religion, philosophy, and science have all wrestled with this question. One of the oldest explanations was the theory of spontaneous generation, which can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and was widely accepted through the Middle Ages.

The Theory of Spontaneous Generation

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) was one of the earliest recorded scholars to articulate the theory of spontaneous generation , the notion that life can arise from nonliving matter. Aristotle proposed that life arose from nonliving material if the material contained pneuma (“vital heat”). As evidence, he noted several instances of the appearance of animals from environments previously devoid of such animals, such as the seemingly sudden appearance of fish in a new puddle of water. [1]

This theory persisted into the 17th century, when scientists undertook additional experimentation to support or disprove it. By this time, the proponents of the theory cited how frogs simply seem to appear along the muddy banks of the Nile River in Egypt during the annual flooding. Others observed that mice simply appeared among grain stored in barns with thatched roofs. When the roof leaked and the grain molded, mice appeared. Jan Baptista van Helmont, a 17th century Flemish scientist, proposed that mice could arise from rags and wheat kernels left in an open container for 3 weeks. In reality, such habitats provided ideal food sources and shelter for mouse populations to flourish.

However, one of van Helmont’s contemporaries, Italian physician Francesco Redi (1626–1697), performed an experiment in 1668 that was one of the first to refute the idea that maggots (the larvae of flies) spontaneously generate on meat left out in the open air. He predicted that preventing flies from having direct contact with the meat would also prevent the appearance of maggots. Redi left meat in each of six containers ( Figure 2 .2 ). Two were open to the air, two were covered with gauze, and two were tightly sealed. His hypothesis was supported when maggots developed in the uncovered jars, but no maggots appeared in either the gauze-covered or the tightly sealed jars. He concluded that maggots could only form when flies were allowed to lay eggs in the meat, and that the maggots were the offspring of flies, not the product of spontaneous generation.

In 1745, John Needham (1713–1781) published a report of his own experiments, in which he briefly boiled broth infused with plant or animal matter, hoping to kill all preexisting microbes. [2] He then sealed the flasks. After a few days, Needham observed that the broth had become cloudy and a single drop contained numerous microscopic creatures. He argued that the new microbes must have arisen spontaneously. In reality, however, he likely did not boil the broth enough to kill all preexisting microbes.

Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729–1799) did not agree with Needham’s conclusions, however, and performed hundreds of carefully executed experiments using heated broth. [3] As in Needham’s experiment, broth in sealed jars and unsealed jars was infused with plant and animal matter. Spallanzani’s results contradicted the findings of Needham: Heated but sealed flasks remained clear, without any signs of spontaneous growth, unless the flasks were subsequently opened to the air. This suggested that microbes were introduced into these flasks from the air. In response to Spallanzani’s findings, Needham argued that life originates from a “life force” that was destroyed during Spallanzani’s extended boiling. Any subsequent sealing of the flasks then prevented new life force from entering and causing spontaneous generation ( Figure 2 .3 ).

- Describe the theory of spontaneous generation and some of the arguments used to support it.

- Explain how the experiments of Redi and Spallanzani challenged the theory of spontaneous generation.

Disproving Spontaneous Generation

The debate over spontaneous generation continued well into the 19th century, with scientists serving as proponents of both sides. To settle the debate, the Paris Academy of Sciences offered a prize for resolution of the problem. Louis Pasteur, a prominent French chemist who had been studying microbial fermentation and the causes of wine spoilage, accepted the challenge. In 1858, Pasteur filtered air through a gun-cotton filter and, upon microscopic examination of the cotton, found it full of microorganisms, suggesting that the exposure of a broth to air was not introducing a “life force” to the broth but rather airborne microorganisms.

Later, Pasteur made a series of flasks with long, twisted necks (“swan-neck” flasks), in which he boiled broth to sterilize it ( Figure 2 .4 ). His design allowed air inside the flasks to be exchanged with air from the outside, but prevented the introduction of any airborne microorganisms, which would get caught in the twists and bends of the flasks’ necks. If a life force besides the airborne microorganisms were responsible for microbial growth within the sterilized flasks, it would have access to the broth, whereas the microorganisms would not. He correctly predicted that sterilized broth in his swan-neck flasks would remain sterile as long as the swan necks remained intact. However, should the necks be broken, microorganisms would be introduced, contaminating the flasks and allowing microbial growth within the broth.

Pasteur’s set of experiments irrefutably disproved the theory of spontaneous generation and earned him the prestigious Alhumbert Prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1862. In a subsequent lecture in 1864, Pasteur articulated “ Omne vivum ex vivo ” (“Life only comes from life”). In this lecture, Pasteur recounted his famous swan- neck flask experiment, stating that “…life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.” [4] To Pasteur’s credit, it never has.

- How did Pasteur’s experimental design allow air, but not microbes, to enter, and why was this important?

- What was the control group in Pasteur’s experiment and what did it show?

- K. Zwier. “Aristotle on Spontaneous Generation.” http://www.sju.edu/int/academics/cas/resources/gppc/pdf/Karen%20R.%20Zwier.pdf ↵

- E. Capanna. “Lazzaro Spallanzani: At the Roots of Modern Biology.” Journal of Experimental Zoology 285 no. 3 (1999):178–196. ↵

- R. Mancini, M. Nigro, G. Ippolito. “Lazzaro Spallanzani and His Refutation of the Theory of Spontaneous Generation.” Le Infezioni in Medicina 15 no. 3 (2007):199–206. ↵

- R. Vallery-Radot. The Life of Pasteur, trans. R.L. Devonshire. New York: McClure, Phillips and Co, 1902, 1:142. ↵

Allied Health Microbiology Copyright © 2019 by Open Stax and Linda Bruslind is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Advertise with Us

- Privacy Policy

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Francesco redi and spontaneous generation.

The theory of Spontaneous Generation proposed that life or living organisms could be “spontaneously generated” from non living matter. Similar to Louis Pasteur’s spontaneous generation experiment , the 17th century Italian scientist Franceso Redi conducted an experiment to refute the theory of Spontaneous Generation nearly 200 years earlier.

Controlled Experiment by Redi

Francesco Redi showed that maggots do not spontaneously arise from decaying meat. To prove this he designed a simple controlled experiment, now referred to as the “Redi Experiment.” The idea of a controlled experiment is that two tests are identical in every aspect, except for one factor. When carried out simultaneously, the hypothesis is that this differing factor (called the “manipulated variable”) is the cause of the different results in each experiment.

Redi’s Experiment Explained

2. After a short period of time Redi observed maggots (fly larvae) on the decaying meat of the open jar. There were no maggots on the meat in the covered jar.

3. Redi concluded that the flies laid eggs on the meat in the open jar which caused the maggots. Because the flies could not lay eggs on the meat in the covered jar, no maggots were produced. Redi therefore proved that decaying meat did not produce maggots.

Try it at Home

With a few simple items, you can try the same spontaneous generation experiment at home.

You’ll need:

Jars with Lids

Cheesecloth

Rubber Bands

- Slice up an apple and put a few pieces in each of 3 jars.

- Put a lid tightly on one jar.

- Put some cheesecloth on top of another jar, securing it with a couple of rubber bands.

- Leave the third jar uncovered.

- Set the jars out in an open area for a couple of days.

You may notice no flies or maggots on the jar with the lid, some flies or maggots on top of the cheesecloth (not inside the jar), and even some maggots or flies inside the open jar.

What does this experiment prove? Did your results match Francesco Redi’s spontaneous generation experiment?

Related Articles

Spontaneous Generation: Redi’s Experiment with Learning Objectives

The Laws of Life: Louis Pasteur

The Spontaneous Generation Dispute

Bastian and Pasteur on Spontaneous Generation

Originally published in The American Naturalist, Vol. 10, No. 12, Dec. 1876, pp. 730-734 by …

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lessons and Courses on Microbiology

FRANCESCO REDI (1626-1697)

Francesco Redi, an Italian scientist was the first scientist to challenge the theory of spontaneous generation by demonstrating that living organisms did not actually originate from non-living things. He developed a scientific experiment to test the spontaneous creation of maggots from fresh meats using two jars (one of the jars was left open while the other was closed).

Redi was famously known for his work on spontaneous generation or abiogenesis . He challenged the concept of abiogenesis by showing that maggots on decaying meat came from fly eggs deposited on the meat and not from the meat itself. Redi explained that flies land on exposed meat and lay their eggs which eventually hatch to produce maggots.

Redi performed series of experiments in the early 1670’s in which he covered jars of meat with fine lace that prevented the entry of flies into the jars. Because the meat was covered, no maggots were produced, and this led Francesco Redi to drop the notion of spontaneous generation.

Francesco Redisuccessfully challenged and refuted the theory of spontaneous generation through his work on maggot and flies, in which he showed that maggots on meat came from egg flies. Though his work was known, the ideaof spontaneous generation was not dropped as other scientist like John Needham continued from where he stopped to unravel the mystery behind it.

Barrett J.T (1998). Microbiology and Immunology Concepts. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers. USA.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23 rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News , 45(1):3–13.

Slonczewski J.L, Foster J.W and Gillen K.M (2011). Microbiology: An Evolving Science. Second edition. W.W. Norton and Company, Inc, New York, USA.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5 th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Share this:

Discover more from #1 microbiology resource hub.

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Related Posts

Introduction to (Medical) Bacteriology

Microbial Growth

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Redi experiment (1665) As late as the 17th century, some biologists thought that some simpler forms of life were generated by spontaneous generation from inanimate matter. Although this was rejected for more complex forms such as mice, which were observed to be born from mother mice after they copulated with father mice, there remained doubt for such things as insects whose reproductive cycle ...

Having observed the development of maggots and flies on decaying meat, Redi in 1668 devised a number of experiments, all pointing to the same conclusion: if flies are excluded from rotten meat, maggots do not develop. ... Louis Pasteur. Louis Pasteur's 1859 experiment is widely seen as having settled the question of spontaneous generation.

Francesco Redi was an Italian physician and poet who demonstrated that the presence of maggots in putrefying meat does not result from spontaneous generation but from eggs laid on the meat by flies. ... but from seeds or eggs too small to be seen. In 1668, in one of the first examples of a biological experiment with proper controls, Redi set up ...

The Swan-Neck flask experiment by Pasteur ultimately debunked the spontaneous generation theory. ... In this experiment, Redi set up 3 jars of various conditions. The first jar was open and let flies to enter the jar. The second jar was tightly to prevent flies from entering. And the last jar was covered with a mesh.

Redi's Experiment and Needham's Rebuttal. In 1668, Francesco Redi, an Italian scientist, designed a scientific experiment to test the spontaneous creation of maggots by placing fresh meat in each of two different jars. One jar was left open; the other was covered with a cloth. ... Pasteur's Experiment. Louis Pasteur, the notable French ...

Pasteur then entered a contest sponsored by The French Academy of Sciences to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation. Similar to Spallanzani's experiments, Pasteur's experiment, pictured in Figure 1.13, used heat to kill the microbes but left the end of the flask open to the air. In a simple but brilliant modification, he heated the neck of the flask to melting and drew it out into a ...

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 - 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. [1] He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", [2] [3] and as the "father of modern parasitology". [4] [5] He was the first person to challenge the theory of spontaneous generation by demonstrating that maggots come from eggs of flies.

However, one of van Helmont's contemporaries, Italian physician Francesco Redi (1626-1697), performed an experiment in 1668 that was one of the first to refute the idea that maggots (the larvae of flies) spontaneously generate on meat left out in the open air. ... Pasteur's experiment consisted of two parts. In the first part, the broth ...

The theory of Spontaneous Generation proposed that life or living organisms could be "spontaneously generated" from non living matter. Similar to Louis Pasteur's spontaneous generation experiment, the 17th century Italian scientist Franceso Redi conducted an experiment to refute the theory of Spontaneous Generation nearly 200 years earlier.

Francesco Redi, an Italian scientist was the first scientist to challenge the theory of spontaneous generation by demonstrating that living organisms did not actually originate from non-living things. He developed a scientific experiment to test the spontaneous creation of maggots from fresh meats using two jars (one of the jars was left open while the other was closed).